Around the Place de la République, you will find one of the oldest places in Paris attesting to the Jewish cultural heritage of Paris: the synagogue of Nazareth. But also very active cultural institutions such as the Cercle Bernard Lazare, the Center Medem and the Maison de la Culture Yiddish.

By order of June 29, 1819, King Louis XVIII authorized the Consistory to build the first major synagogue in Paris on rue Notre-Dame-de-Nazareth.

It was inaugurated in 1822. A courtyard welcomed the faithful behind a sober facade. Inside, the thirteen massive columns were particularly noticeable. The bimah was installed in the center and the decorative motifs recalled neoclassicism.

At the rear of the building was also installed a prayer room in order to follow the tradition of the Portuguese Jews living in the area. deteriorated rapidly and various development or reconstruction projects were then considered. Finally, the architect Alexandre Thierry reconstructed the entire building, removing the small room from the back. Orientalist and biblical references mingled with the new project.

The facade remains sober but the crowning of the portal presence of the motifs of Byzantium and the Middle East. We also see a very beautiful rose window. Twelve arches are drawn in the project to recall the twelve tribes. On the women’s floor, three arches are inspired by the three prophets. A large arch closes the sanctuary.

The vault is painted blue with golden stars walking around it. The tevah is located in the center. The synagogue of Nazareth was inaugurated in 1852. It still remains today one of the most representative synagogues of Parisian Jewish heritage.

Bernard Lazare, born in Nîmes in 1865, committed writer and leftist, published in 1894 “Anti-Semitism, its history and its causes”. Two years before the Dreyfus Affair. He was also very involved in defending this cause, as well as the fate of the Armenians persecuted in 1902. He died a year later. At the corner of Turbigo and Borda streets, a square now bears his name.

Not far from there was located the Cercle Bernard Lazare, opened in 1954. It was a very active cultural meeting place, committed to the defense of republican values and the Israeli-Arab dialogue. Conferences, concerts, publications of the Cahiers Bernard Lazare were organized and the CBL was also very involved in the European Days of Jewish Cultures and Heritage.

Two other places in Paris perpetuate the memory of Parisian Jewish history and the teaching of Yiddish. Vladimir Medem, a great theorist of the Bund workers movement and committed politician, participated in the 1905 Revolution and distinguished himself during the two 1917 Revolutions.

Many institutions around the world bear his name. In Paris, the Medem Arbeiter Ring Center is a secular Jewish organization registered in the socialist movement and attached to the Yiddish culture. organizes sixty cultural events per year, as well as language workshops (Yiddish, Hebrew, Judeo-Spanish and Judeo-Arabic).

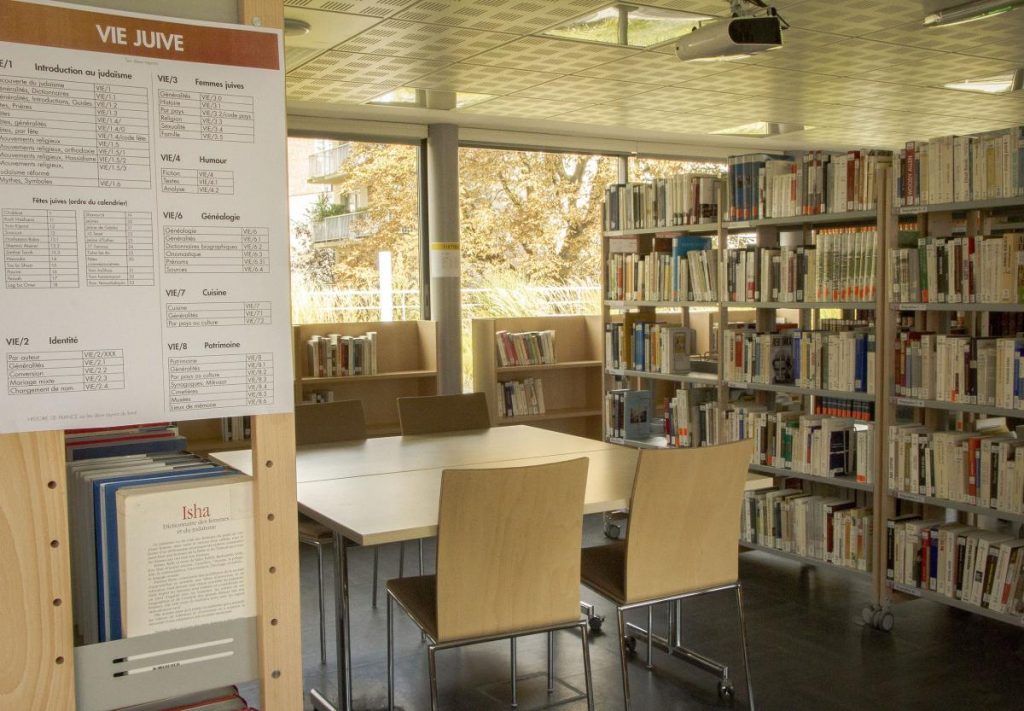

Closeby, the House of Yiddish culture which is dedicated to the conservation of the heritage and the dissemination of Yiddish culture in France and in Europe and the promotion of Yiddish as a language to audiences from all walks of life. Besides its cultural activities and language workshops, it has an important library.

Following the resurgence of antisemitic acts in France in the year 2000 and its continuity, many Jews moved, leaving the working-class areas where such attacks became banal, preferring to rent much small apartments in expensive neighborhoods where they felt safer. Two geographic zones have thus welcomed many Jews in the last twenty years.

The East, around the 11th and 12th arrondissements of Paris and the nearby suburbs of Saint-Mandé and Vincennes. And the West, around the 16th and 17th arrondissements and the suburbs of Neuilly, Levallois and Boulogne. But the link to those latter arrondissements is more ancient. In the 19th century, a small part of Parisian Jews migrate to the chic neighborhoods of the western part of Paris. Mostly towards the Parc Monceau area in the 17th arrondissement and the Victor Hugo place in the 16th.

Nowadays, the 17th arrondissement counts 40 000 Jews among the 300 000 living in Paris and its suburbs. Synagogues, restaurants, butchers, delis, schools… The cultual and cultural Jewish life is profuse in this area.

Nevertheless, the arrondissement was first influenced by a more ancient history, notably concerning the impact of important families. Among them, the Pereire brothers. Born in the city of Bordeaux, Emile in 1800 and Isaac in 1806, the pursued their financial career in Paris. Following the saint-simonianist philosophy, they wish to enlarge the economical development beyond its simple sphere. That its flourishment would enable the embitterment of the social condition of all the Parisians. This motivated the launching of grand scale projects. With the help of the State, the Pereire participated in the Universal Exhibit of 1855 and more important the renewal of the Haussmann neighborhood. They also developed the Crédit immobilier, a real estate bank, as well as the Gas heating company. And what they are also well known for, rail and sea transport.

In the 17th arrondissement and the nearby 8th arrondissement, they divide into plots parts of the Parc Monceau. Emile Pereire builds himself a hotel at 10 rue Alfred de Vigny. The brothers invest in real estate projects avenue de Villiers, boulevard Malesherbes and avenue de Wagram. And not far from those streets, building the Saint-Lazare train station. Elected Members of Parliament in the 1860s, the Pereire brothers fervently fought for the gratuity of education. Today, a square and a boulevard carry their name in the 17th arrondissement.

The Nissim de Camondo Museum , located on rue Monceau, is another important place linked to Jewish heritage in this neighbordhood. Abraham and Nissim Camondo, ennobled Italian bankers, bought the piece of land on a part of which the Museum stands today. Isaac Camondo, Abraham’s son, an astute art collector, made one of the greatest donations in the Louvre’s history, also enabling living artists, among which the impressionists, to find a place on its walls.

In 1911, Moïse Camondo, Nissim’s son, has the rue Monceau hotel rebuilt with the help of the architect René Sergent. A building inspired by the Petit Trianon’s architecture. Respected art collector like his brother, Moïse bequeaths the hotel and the artworks he placed there to the nation’s l’Union centrale des arts décoratifs (UCAD) in 1924. On the sole condition that the museum carries the name of his son Nissim, who died fighting during World War I. It’s considered today one of the most beautiful museums of Paris. Among the many books and artworks, a few Jewish books and objects still decorate it.

The 16th arrondissement has been welcoming different tendencies of Judaism for more than a century. Both orthodox and liberal. The area also hosts the biggest Jewish library in Europe.

A building mixing orthodox practice and modern architecture is located on rue Montevideo. Following a few resettlements of this community started in 1892 by the Société du culte traditionnel israélite, at avenue Malakoff, then rue Lalo, it was finally established rue Montevideo in 1934.

Built by the architects Julien Hirsch and Roger Kohn, this confined building of five floors welcomes the synagogue in its community center. The magen David isn’t a secondary decorative motif, as it is often the case in more ancient synagogues.

Here, it appears in different manners and colors, as one can witness on its concrete vault. The synagogue’s façade and its interiors are quite sober. Whether it be the bimah at its center or the metallic decorations.

On rue Copernic, close to the Victor Hugo square, stands the synagogue of the liberal Judaïsme En Mouvement (JEM). It was inaugurated in 1907 and headed by Rabbi Louis-Germain Lévy. In the beginning of the 1920s, the synagogue evolved architecturally.

This was caused by its extension and constructions in the courtyard. Mutations also occurred at the end of the 1960s. All those architectural changes explaining the different influences visible inside, between biblical inspiration and artistic movements of the 20th century.

The JEM Copernic synagogue has been the victim of two attacks. First during the Nazi Occupation and later on in 1980. The latter terrorist attack by a Palestinian group has caused the death of 4 persons and many wounded. Admittedly, the early 1980s antisemitic attacks and even more so the ones which started in 2000 have forced a more scrupulous securing of synagogues and Jewish schools, but they haven’t affected the worship, as is the case also regarding the liberal movement which attracts a growing number of Parisian Jews.

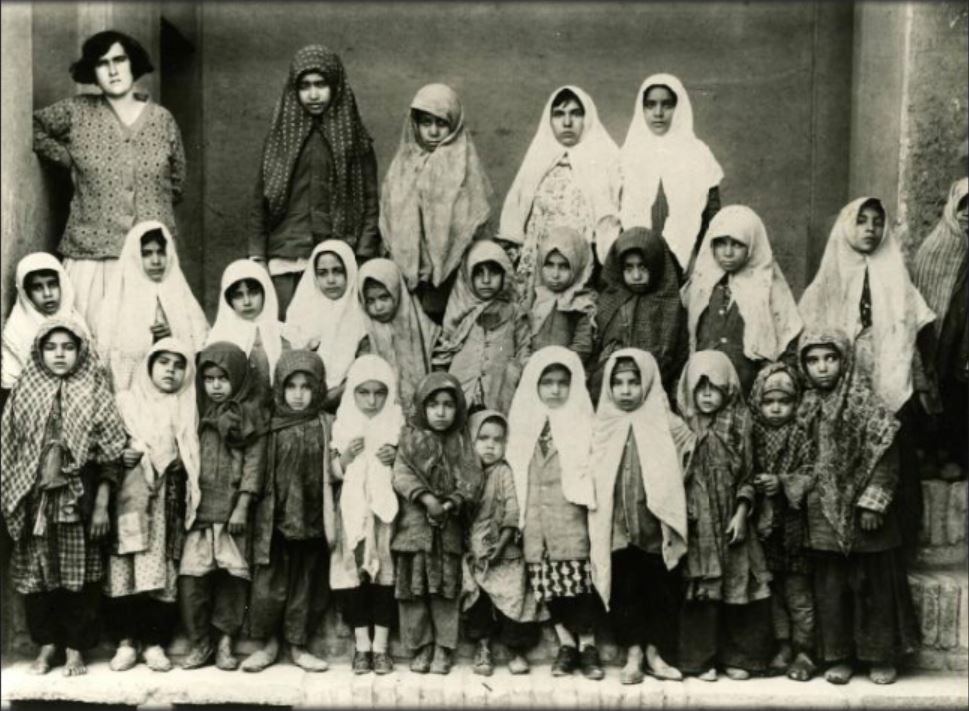

Hotspot of historical and cultural research on Jewish heritage, the Alliance Israélite Universelle’s library possesses the biggest European archives in those fields. Formerly at rue La Bruyère (in the 9th arrondissement), today it’s located rue Michel-Ange. The AIU, famous for its network of schools in Europe, Israel, au Morocco and North America, was created in 1860. With the aim of defending and sharing Jewish culture as well as promoting Human rights.

Nowadays, the AIU keeps sharing cultural and educational values in France and the French speaking world. College studies are also proposed by a cursus on « Biblical and Jewish Humanities » through its Institut Européen Emmanuel Levinas and the Collège des Etudes Juives – Beth Hamidrach.

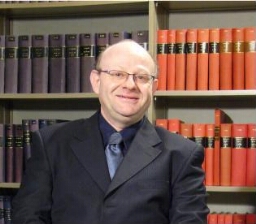

Interview with Jean-Claude Kuperminc, Director of AIU’s Library

Jguideeurope: Under what circumstances was the AIU’s Library created?

Jean-Claude Kuperminc: When the Alliance Israélite Universelle was created in 1860, it immediately required documentation to understand the fate of the Jews she wished to defend throughout the world. Thus, she establishes a resource center which would quickly become a patrimonial and savant library, under the influence of the AIU’s first leaders. Among which Salomon Munk, Isidore Loeb, the Great rabbis Israël Levi and Zadoc Kahn, who are also key figures in Jewish studies in France. The library receives books, theses, brochures, both from rabbis and the academic world. She also acquires important collections which are the core of its wealth, thanks to the outstanding donation of a benefactor, Benjamin Louis Mayer Rothschild (not related to the famous family) : the Salomon Munk Funds, exceptional manuscripts by Samuele David Luzzatto, the Zadoc Kahn Funds and the Bernard Lazare Funds. In 1939, while it just settled in functional offices at 45 rue La Bruyère, the library already holds more than 50 000 documents.

During the war, it is occupied and plundered by the Nazis working for Alfred Rosenberg. The books and documents are taken to Frankfurt where they’re part of a gigantic Jewish library. Fortunately, it was recuperated the American troops at the end of the war. Between 1945 and 1955, many books are given back to the AIU. Part of the archives, which were stolen by the Nazis and taken again by the Soviets in 1945, only emerged at the end of the 20th century and reintegrated our shelves in 2000. We have called it the Moscow Funds of the AIU archives.

Between 1937 and 1989, the library is resettled at the ground floor of the courtyard of rue La Bruyère. A new building is created there in 1989. Unfortunately, the AIU must leave its private mansion in 2016. Since then, the library welcomes its readers in one of its other historical locations, the former Ecole normale israélite orientale (ENIO) at 6 bis de la rue Michel-Ange, an address it left in 1937. Thus, we’ve come full circle. You can find on this link a movie presenting the library’s history in its former premises.

How many documents can be found at the library today and how do we have access to them?

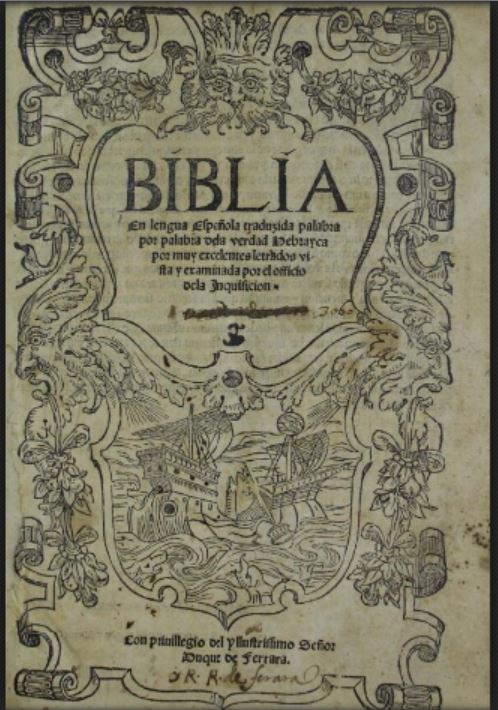

It’s always hard to establish a detailed account. The library holds about 150 000 books, 3000 collections of newspapers, 1000 ancient manuscripts and 15 incunabulum works. She’s also the proud owner of 2 million items of archives of the AIU institution, essential for 19th and 20th century Jewish studies, particularly the Balkan, Mediterranean and Middle Eastern areas. Add to that 30 000 photos, movies, and sound recordings, then you’ll have an idea concerning the variety and importance of those collections. Since 2005, the library participates in the RACHEL network, which offers a catalogue of all the documents owned by several Parisian Jewish libraries. Since 2018, the AIU proposes its own digital library which gives a free access, free of charge, to more than 20 000 documents (books, newspapers, photos, movies, virtual exhibitions…) on the web.

Do you receive many requests for international research? Concerning especially cities, monuments or genealogy?

Much of our audience comes from abroad, including academics and PhD students. They use the archives of the AIU, but also our collections of old documents. We are partners of the Jewish Genealogy Circle, which actively works to locate names of people in our archives. The AIU was particularly effective in researching the life of its school personnel from 1860 to 1940 around the world. In our digital library, we have privileged documents on synagogues, with nearly 200 photographs and 80 books. You can find the testimony of a library reader at this link.

Among the documents received recently concerning cultural heritage, which one particularly interested you?

Two initiatives caught my attention. These are exceptionally beautiful books of historical interest on two of the most important Parisian synagogues: the Buffault synagogue, dedicated to the Sephardic cult of Portuguese rite, and the Synagogue de la Victoire. In both cases, the faithful of these places of worship have done a remarkable job of historical research and presentation in order to highlight the history of these prestigious buildings which have been illuminating the Parisian Jewish landscape for 150 years.

La synagogue de la Victoire : 150 ans du judaïsme français. Paris : Editions du Porte-plume, 2017.

Elie Balmain et Claude Nataf, Buffault : documents fondateurs et contractuels du Temple hispano-portugais. Paris : Editions E. Balmain, 2018

Which Parisian place of European Jewish cultural heritage do you think deserves to be highlighted?

Professionally, I would say the site of rue Michel-Ange, which today houses the library, the Gustave Leven School and the ENIO synagogue. The building is modern (built in 1965, rehabilitated in 2011), but the place is steeped in history with the statue of Moses, imitating Michelangelo, which was already present when the ENIO prepared the young teachers of the AIU to their future profession in schools. This is also where the philosopher Emmanuel Levinas lived as director of the ENIO. On a personal level, I will opt for the Fleischman Foundation, in the heart of the Pletzl, 18 rue des Ecouffes. It was in this shtibel that my father celebrated his bar-mitzvah in 1935. It’s one of the few locations still representative of the places of worship of Jewish immigrants who arrived from Poland in the 1920s.

Today two large bridges cross the Bosporus, completely integrating the Anatolian part of the city with Istanbul proper. Formerly, crossing was by ferry only. Consequently, the Asian districts of Istanbul and its neighboring villages lived according to another rhythm, somewhat at the margins of the pulsing heart of the city. In Kuzgunçuk, a little to the north of Üsküdar, is a significant Jewish quarter nicknamed Little Jerusalem. Today it is home to two beautiful synagogues. The lovely Hemdat Israel Synagogue is also located on the Asian side, near the Haydarpasa train station. The big city looms nearby, but Kuzgunçuk has managed to preserve the atmosphere of a village, a tranquil oasis with views of the Bosporus to the west. Icadiye Street is the heart of the quarter, inhabited by Greeks, Armenians, and, above all, by Jews for more than 400 years. Today, not much more than a few Hebrew inscriptions on stone or wood facades remain to recall the Jewish past.

The elegant Beth Yaakov Synagogue was built in 1878 to take the place of an earlier synagogue on the same site. Restored at the end of the nineteenth, the synagogue opens onto a beautiful garden. Notice the original landscapes on the ceiling.

A Greek church and an Armenian church stand nearby. Higher up the hillside, the Beth Nissim Synagogue serves as a place of worship during the winter months. Constructed in 1840, it is noteworthy for its richly painted hall. The aron dates from the end of the eighteenth century.

A slight distance from the center of Kuzgunçuk, the Nakas Tepe Jewish cemetery is a worthwhile destination during your visit. Many Jews had themselves buried here, even if they lived in the city, because the Asian soil was considered closer to the Holy Land. One can see a few beautiful gravestones from the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. As with other Jewish cemeteries in the city, it has been thoroughly pillaged in the last decades. Its stones have served as construction material for the shanties built by the immigrants from Anatolia.

Descending along the banks of the Bosporus toward the south and after passing Üsküdar, you will arrive at Haydarpasa, a superb train station. Dating from the beginning of the twentieth century, it was the terminus of trains linking the capital to its Ottoman possessions of the Middle East, Jerusalem, Mecca, and Medina. Many Jews arriving in Kuzgunçuk settled in this quarter, whose development was in full swing at the time and where the beautiful new Hemdat Israel Synagogue had just opened in 1899 with the attendance of a number of Ottoman and western dignitaries. The building is surrounded by a garden that, although not apparent from the outside, contains a large rectangular prayer hall with a painted ceiling and beautiful wall decorations. The aron is installed in the middle of one of the broad walls across from the tevah, an arrangement typical of certain Italian synagogues. Not far from here, one can visit a small, well-preserved Jewish cemetery.

In the nineteenth century, the villages along the Bosporus sheltered numerous “minorities” -Greeks, Armenians, and Jews. Swallowed up today by the great metropolis, Ortaköy, Arnavutköy, Bebek, Yeniköy, and others have become sought-after residential areas with interesting traces of this Jewish past, most noticeably in Ortaköy.

On the hills and beyond extend the elegant new neighborhoods of Istanbul. This is where many wealthy Jewish families have settled since the interwar period, and especially in the last few decades, preferring its beautiful, spacious avenues to Pera’a cramped streets. With the large Beth Israel Synagogue and the administrative offices of most Jewish clubs and associations, today the heartbeat of the Jewish community in Istanbul is felt most strongly in Nisantasi and Sisli. The weekly journal Shalom is also located here, with a small bookstore where one can find books on Turkish Judaism.

The Etz Ahayim Synagogue stands near the Bosporus in Ortaköy along the edge of the isthmus where the great ships cross between the Black Sea and Sea of Marmara. The site is one of striking beauty, even if a rather plain and uninteresting modern building has replaced the former structure, which was destroyed by fire in 1941. The original synagogue, which was one of the oldest in Istanbul, was reconstructed in the eighteenth century. In the last few decades, a small Jewish community has formed in Ortaköy. Many of its members came from the great bazaar quarter, where their homes were destroyed by a fire. The synagogue’s magnificent marble aron, featuring two finely carved neoclassical columns and carved wood doors, dates from the early period. Nearby stands the small building housing the Midrash, saved from the 1941 fire and which for more than a century had served the quarter’s Ashkenazic synagogue.

As you walk around Ortaköy, notice the row of eighteenth-century Jewish corbelled wood houses (los diziogos) on Bulguruc Street. At the top of the hill is a small Jewish cemetery established in the nineteenth century and later abandoned. Unfortunately, many of the beautiful tombstones have been destroyed.

As you walk north along the Bosporus, you will come to Yeniköy, where a small reconstructed eighteenth-century synagogue is still in use.

The Beth Israel Synagogue is currently the most active and most frequented synagogue in Istanbul. Modern and functional, the building was enlarged in 1952 according to plans by the architect Aran Deragobyan. Especially noteworthy is the lovely stained-glass above the large 500-seat rectangular prayer hall.

Hasköy is the other Jewish suburb of Istanbul, located on the northern bank of the Golden Horn. When the Ottoman Empire was at its height in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, Hasköy was slightly more populous than Balat and contained a greater concentration of elite Jews.

One of the most famous inhabitants of the quarter, the prestigious physician from Granada Moshe Hamon, was an adviser to Sultan Mehmet II the Conqueror. Also in this quarter the first Jewish printing presses were set up. The most renowned educational and cultural institution of the period, the Gvira Yeshiva, established in the sixteenth century by Joseph Nasi is also located here. “There are more than a thousand homes surrounded by gardens in Hasköy, a beautiful spot with good air”, recalled Evliya Tchelebi, the famous Ottoman traveler and diarist of the seventeenth century who wrote about the 17,000 strong Jewish population -at the time the overwhelming majority in the quarter.

Soon after, the quarter began a period of decay, although the old traditions persisted. In 1858, Abraham de Camondo founded the institute that bears his name, the first Jewish school in the capital to teach according to western principles. The large school building of the Universal Israelite Alliance was opened in the same neighborhood in 1899. In 1955, the building became the administrative offices for the rabbinical seminary (which were later moved to Galata). Today it houses the main Jewish hospice for the elderly in Istanbul (at Köy Mektep Street). Urban reconstruction and the rerouting of major thoroughfares have devastated this neighborhood even more than that of Balat. Only two of the more than thirty synagogues in Hasköy remain.

The Maalem Synagogue was built in 1754. Recently restored after years of abandonment, this elegant building stands in a courtyard protected by a high wall. Two marble columns flank the porch, which opens onto a large, almost square hall with six pillars. The tevah stands in the middle of the room and has the form of a ship, like that of the Ahrida Synagogue. Beneath a small dome with floral decorations, is the aron, whose wooden doors have richly gilt moldings. Simpler and more restrained in the past with its light plastered wall contrasting with the darkness of the wooden pews, the hall interior today alternates between sky blue and white. The restorations have brought to life a part of the mural decorations.

Hasköy is home today to Istanbul’s main Karaite population. Their kenassa (synagogue), Bene Mikra , is a small wooden building behind a large brick wall. According to local tradition, a Karaite temple already existed on this spot in the Byzantine period. The current building, with its lovely portico flanked by two columns and a sculpted triangular pediment, was rebuilt in the eighteenth century after being devastated by fire. Access to the building is by way of a small staircase. Ilan Karmi notes that “As with all Karaite synagogues, this one is constructed below the ground level in order to respect the biblical passage that states, ‘From the depths, I call you, my God'”. Inside, prayer carpets replace the conventional pews for worshippers. The wooden houses surrounding the temple were formerly inhabited by Karaite families.

The Karaites

This dissident sect of Judaism is characterized essentially by its rejection of the oral law represented by the Talmud. Karaite Jews were living in Byzantium even before the Ottoman invasion, as the writings of the twelfth-century traveler Benjamin of Tudela attest. Of interest is his reference to a community of 500 Karaites in Galata, close to the Bosporus in the present-day Karaköy quarter. More than eighty Karaites communities existed in the territory of the Ottoman Empire, as well as in Syria, Egypt, the Balkans, and especially Crimea.

Going back hill to the north, you will arrive at Hasköy’s large Jewish cemetery, the largest in the city along with that of Kuzgunçuk, on the Asian side of the Bosporus. Half abandoned, the cemetery is today bisected by an urban thoroughfare. The road passes just at the foot of Abraham de Camondo’s tomb, a neo-Gothic mausoleum meant to recall for posterity the grandeur of this enterprising financier, who, although living in Paris, asked to be buried in Istanbul.

The Golden Horn is a small estuary created by two rivers that flow into the Bosporus. From one side of the Golden Horn to the other extend traditional Jewish neighborhoods that arose beginning at the time of Jewish settlement in Istanbul in the Byzantine period. Even at the beginning of the twentieth century, more than half the population of the Balat was Jewish, although many were already leaving the cramped houses of this humid district for the “European city”.

The neighborhoods of the Balat, on the right bank, and of Hasköy, on the other side of the river, have remained vibrant and rather exotic in memories of Istanbul -places where Ladino was spoken and one lived according to the rhythms of Jewish festivals and the Shabbat. The names of synagogues, many of which have since disappeared, recall the Sepharad that everyone keeps close to their hearts (Gerouche-Castile -the exiles of Castile-Catalan, Aragon, Portugal, Senioria…). Many European travelers of the nineteenth century gave terrible descriptions of this quarter. Edmondo de Amicis, for example, described it as “the vast ghetto of Balat stretching out like a foul serpent along the Golden Horn with its mold-encrusted huts.”. Marie-Christine Varol offered a more even-handed portrait in her monograph on the Balat: “All manner of social classes are found mixing in the Balat, from well-off merchants to the most humble street peddlers and ragpickers.”.

As in the rest of Istanbul, the many wood houses were vulnerable to devastating fires. The volunteer fire brigade thus held a key place in the life of the community. The houses near the docks (the Karabas area) have been knocked down to make room for a park and an enbankment. Recent Anatolian immigrants occupy most of the small buildings abandoned by Jews. Only a few Jews still live in the area, notably close to the Ahrida Synagogue. These are mainly poor families living on aid from the community. Some Jewish doctors keep an office in the area, near the large Jewish hospital Or Ha-Haïm, which is still active. The inscriptions on the stone facades of the houses and several synagogues still standing in the area evoke memories of its former life. A visit to Balat and Hasköy necessitates a full day.

The fire of 1911

“In 1911, part of the Or Ha-Haïm hospital located in Balat burst into flames and was engulfed in fire. The entire Dibek quarter, including the Gerouche Synagogue and the two Israelite Alliance schools, a part of the Sigri quarter with its synagogue Pol Yacham, the entire Hevra quarter and its synagogue and Talmud Torah, and a large part of Balat fell prey to the flames. Caption: 520 buildings destroyed, 1000 families without shelter…Outside the municipal and communal aid, the gifts of strangers are rapidly amounting to more than 60,000 francs.”

Avram Galanté, History of the Jews of Turkey. (Istanbul: Isis, 1985).

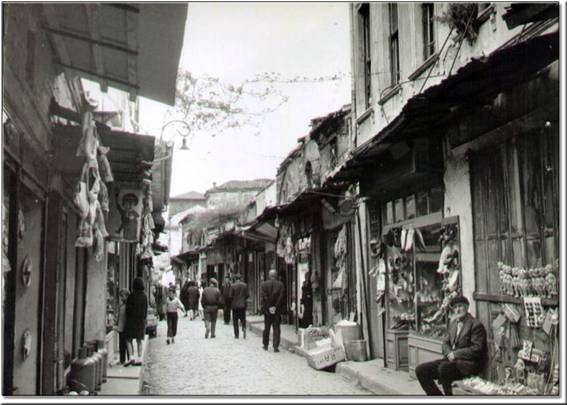

The lively main street of Kürkçü Cesmesi, like the nearby Leblebciler and Lapincilar, is the center of commercial Balat and animated every day except the Shabbat. On Saturdays, the area is dead, a place where even the Turkish and Greek merchants respect the sacred day of rest. Most of the shops at the front of the houses are owned by Jews. The area was known for the manufacture of the fez until this traditional headpiece was outlawed by the republican authorities in 1928. There are also cobblers and makers of Turkish slippers, often Jews from Georgia (los gurdjis). At 6 and 8 Eski Kasap, the street perpendicular to Kürkçü Cesmesi, you can still see two lovely Jewish homes, with a Star of David on the corbelled facade and the inscription “Prosperity on the family”.

The Ahrida Synagogue is the oldest continuously active synagogue in Istanbul. Founded in the fifteenth century by Jews from the Macedonian city of Ohrid, it is also incontestably the most beautiful. The synagogue has kept the name of the small Romaniote community that established it, even though this community was absorbed by Jews arriving from the Iberian Peninsula, who gave the temple its splendor. According to legend, the false Messiah Sabbataï Zevi once preached here.

The main building was rebuilt at the end of the seventeenth century and restored several times thereafter, each time keeping the general outlines of the original design. The large rectangular prayer hall is crowned by a wooden dome, and its ceiling is painted with elegant, typically Ottoman floral motifs. Resplendent with eight columns and ten large windows, the synagogue is luminous. The most recent large-scale restorations, completed in 1992, have returned the hall to its former design, most notably by getting rid of the women’s balcony. As in earlier times, women follow the service from an adjacent hall separated from the main worship space by perforated panels. A unique tevah stands in the center of the hall. Made of varnished wood in the form of a ship, it represents Noah’s Ark and also explicitly evokes the caravels that carried Jews fleeing Spain. The prow points toward the aron, which features magnificent ivory and mother-of-pearl inlaid wood doors. Two other buildings are located in the garden, the Midrash and a heavy stone and brick structure, the old odjara. The latter today serves as a hospice.

Several hundred feet from the Ahrida Synagogue stands the Yanbol Synagogue , the other main synagogue preserved in Balat. Bearing the name of the small city in Bulgaria where the members of the founding community originated, the synagogue was rebuilt in the eighteenth century and restored several times subsequently. Illuminated by its numerous windows, the large hall is crowned by an elegant wooden ceiling decorated with floral and other motifs. The capitals of the columns are finely carved and painted. The tevah in the middle of the hall faces the aron, whose wooden doors are inlaid with mother-of-pearl and ivory like those of the Ahrida Synagogue.

Nearby, at the corner of Feruh Kahya and Mahkme Alti streets, you can visit the old cavus Hammami , frequented by Jews of the quarter, who called it “el bano de Balat”. In both the men’s and women’s areas of the facility, there is a basin reserved as a mikvah for purification.

Going back up the hill toward Balat and the Saint Savior in Chora (Kariye Camii), famous for its mosaics, you will come to the impressive Ichtipol Synagogue . Made completely of wood, the synagogue has a beautiful round stained-glass window bearing two interlaced Stars of David. It was established in the first years of the Ottoman Empire by Jews from the small Macedonian town of Ichtip. Devastated by several fires, it was reconstructed for the last time in 1903. facing at number 63 and 67 on the same street are two beautiful homes notable for their corbelled wooden facades and finely carved decorations. They were once occupied by Jewish families of the area, who, even at that time, had already begun to occupy parts of the neighboring Greek enclave.

The remains of several other synagogues can be found in Balat, sometimes reduced to a simple door, such as that of the Kastoria Synagogue, at 132 Hoca Cakir Street. Along Demir Hisar Street, one can make out the ruined walls of the Eliahuh (at number 231) and Sigri Synagogues. The former Egri Kapi cemetery, which closed in 1839, is now completely abandoned and being devoured by neighboring construction projects. The tombstones bearing inscriptions have been transported to the cemetery in Hasköy on the other side of the Golden Horn.

Lying atop a hill dominating the Bosporus to the north of the Golden Horn, the “European city” of Pera grew up in the middle of the nineteenth century. A place where earlier one could find the shop counters of Genoese merchants, the architecture of Beyoglu, as the Turks call it, is western. Its grand structures such as the covered passages, recall those of Paris, London, or Berlin. Western nationals, taking advantage of the privileges granted by the sultan to those doing business with the empire, settled here and were followed by a number of “minority” populations, including Greeks, Armenians, and Jews. The only remaining part of Istanbul that has no significant mosque, Pera is located across from Stambul, the old city on the other side of the Golden Horn. In contrast, one finds numerous Orthodox, Catholic, and Protestant churches close to its large street, today called Istikal Street.

According to the travel guides from the era when this quarter became the sixth arrondissement of Istanbul in 1857, Beyoglu was an “extension of Europe” characterized by embassies, wine merchants and milliners, cabarets and theaters, luxury hotels such as the Pera-Palas, and Western-style educational institutions such as the Francophone Galatasaray. An intellectual, political, and diplomatic center of the cosmopolitan Ottoman capital in the last decades of the Empire, Pera was also the residential neighborhood of choice for elite Jews open to the ideas and models of the west. Connected by a subterranean funicular to Galata-Karaköy near to the passengers’ port on the Bosporus, Pera is also home of the Neve Shalom Synagogue, the largest synagogue still active. The Italian synagogue, and the administrative offices of the rabbinate are also located here.

The Neve Shalom Synagogue is situated on a small street near the famous Galata Tower (Galata Kulesi). It was built by Genoese in the fourteenth century in a lively quarter that is still at the center of Jewish life in Istanbul. Near the synagogue, one encounters typical Jewish homes of the period decorated with a Star of David on the pediment. The house at 50 Büyük Hendek Street is a good example. The houses at 5 and 7 Timarci Street have their date of construction engraved on a foundation stone calculated according to both the Hebrew and European calendars. A few of the last surviving grand homes typical of the Ladino way of life remain in this quarter. As Ilan Karmi notes in his guide to Istanbul, “Constructed around a central courtyard, these homes, commonly called yahudi hani (Jewish houses), could be comfortably inhabited by a large extended family or a congregation”. One of the best preserved houses of this type is located at 56 Serdari Ekrem Street.

The Neve Shalom Synagogue , designed by the architects Elio Ventura and Bernard Motola, was built in 1951 on the site of a small prayer hall that it replaced. The elegant building has a large hall able to hold as many as 500 people and is decorated with a splendid rose window on the facade imported from Great Britain. Be sure to notice the magnificent woodwork on part of the walls

The tevah and aron are elevated and face the worshippers’ benches, as in most of European synagogues dating from the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries. In the entrance is a plaque recalling the terrible attack on 6 September 1986 that left twenty-three dead. Two Arab terrorists managed to enter the prayer hall during Shabbat services, and after killing the old shamash (the “bedaud”), who tried to stop them, opened fire on the congregation. The strong reaction of the Jewish community to the trauma remains acute; despite the solidarity shown by the authorities and the near-total support of public opinion. The synagogue was restored and reopened in May 1987. Each year, a special commemorative service is held for the victims.

Near the Neve Shalom Synagogue at 87 Büyük Hendek Street is the site of the former Knesset Israel Synagogue in what is now a sports club. A little further down the street is a Jewish elementary and high school complex constructed in 1915 during the war, when the Universal Israelite Alliance schools were not permitted to operate; as Francophone institutions, they were naturally the enemies of the Ottoman Turks allied with Germany.

The Italian Synagogue is discreetly located in a harmonious building behind the wall of a small courtyard. Largely remodeled in the early 1930s, the design preserves the original structure dating from 1887. The centuries-old presence of Italian Jews in the Ottoman capital is attested by the memory of the ancient synagogues of Puglia (Apulia) and Messina, which have since disappeared. In 1866, the Italian Jews separated from the rest of the Jewish community, which they judged to be too traditionalist. Supported by the Italian embassy, they obtained the right from Sultan Abdulaziz to form an autonomous congregation, similar to what already existed for the Ashkenazic community and the Karaites. The facade of the synagogue is restrained but harmonious with its rectangular pediment and brick double staircase leading to the entrance. The prayer hall is painted completely white and surrounded by the women’s gallery on the second floor. Today the Italian community numbers only a few hundred faithful.

Imposing and rather austere from the outside, the Ashkenazic Synagogue stands in the middle of the large street connecting Pera to the lower section of the Galata neighborhoods near the Bosporus. This area is the former banking and financial section of the city, revealed by the names of the streets (Bankarlar Street, for example). In the nearby Voyvoda Street, above the sumptuous staircases that he had constructed, you will find the neighborhood of the great financier Abraham de Camondo. The current synagogue, called the German Hebrew Synagogue according to the plaque on its facade, is the last of the city’s three Ashkenazic temples. It is located in an area where Jews from Hungary, Germany, and France settled beginning in the fourteenth century. Approximately 2000 Ashkenazic Jews live in Istanbul today.

The building was constructed in 1900 following a design by architect Gabriele Tedeschi. The beautiful facade is composed of three richly decorated grand arcades crowned by two domes. It recalls the facades of numerous synagogues built in the nineteenth century in cities of the Austro-Hungarian Empire by emancipated bourgeois Jews. And this is not accidental, since many of Istanbul’s Ashkenazim arrived here from Austria, Bohemia, and Hungary and remained Hapsburg subjects. The plaque at the entrance to the synagogue commemorates, among other things, the fiftieth birthday of Emperor Franz-Joseph, whose wife gave to the synagogue the magnificent aron made of carved alder and inlay and crowned by a wooden dome decorated with gold. The ensemble is of an obvious oriental style with carved wood decorations blending Hebew letters with plant motifs. The rectangular hall can hold 1000 people and is crowned with an azure dome flecked with golden stars. The women’s gallery extends on two floors. In all, the building has seven halls. Four are in the basement, which contains a dining area, the mikvah, Midrash, and a small room for morning prayers.

The Jewish Museum of Istanbul , used to be located in the Zulfaris Synagogue, at the end of a small street near the entrance to the funicular (tunnel) and the famous Galata Bridge at the mouth of the Golden Horn. Closed for more than ten years and reopened in 2000, the current building was remodeled in 1890 with a donation by the Camondo family and replaced most of the original edifice dating from the seventeenth century. The museum is located since 2016 near the Neve Shalom synagogue.

Like other synagogues of the “European city”, the Zulfaris Synagogue takes its inspiration from Western models of emancipated Judaism. The imposing marble aron has two arrows on the side and is neo-Gothic in style. It was conceived by one of the architects who constructed Saint Anthony, the Pera quarter’s large, beautiful Catholic church.

The lovely rectangular hall measures 50 ft. x 23 ft. Its second-floor gallery houses a permanent exhibition on the life and history of Turkey’s Jews. Naim Guleryuz, the museum curator and the community’s historian, explained: “We wanted to illustrate six centuries of harmonious existence and to show our fellow believers and others that the Jews of Turkey have actively participated in the life of this country”. Several Sifrei Torahs crowned with the crescent and star are on display, as well as religious objects, decorated with Ottoman symbols. You will discover in the display cases and on the walls examples of the flourishing Jewish and Ladino press from the end of the nineteenth and beginning of the twentieth centuries, as well as portraits of famous Jews of the time in diplomacy, the arts, and even the military. The museum gives information on Jewish scholars who fled Hitler’s Germany and found refuge in Turkey, as well as Turkish diplomats such as the consul of Rhodes, Salahattin Ülkümen, who saved many Jews during the war by giving them Turkish papers.

Saint John’s Wood, Hampstead, and, above all, Golders Green and Stamford Hill are the heart of London’s Jewish life and have numbers of shops. Amusingly enough, most of the shops selling kosher products are now run by Indians.

Opening of the Jewish Museum and the London Museum of Jewish Life

The Jewish Museum was founded by Cecil Roth, Wilfred Samuel and Alfred Rubens in 1932. It was originally located at Woburn House in Bloomsbury. In 1994, it found a new home in Camden Town.

In 1983, the London Museum of Jewish Life (formerly the Museum of the Jewish East End) was opened. Its main ambition was to safeguard and present the Jewish cultural heritage of the East End, which historically was home to the vast majority of Jews before they moved to other areas, particularly those in the north. Over time, the museum also became involved in presenting Jewish life in other areas, sharing memories of the Holocaust and organising anti-racism programs.

The two institutions, remaining in their original locations, were brought together under the management of the Jewish Museum in 1995. Fifteen years later, the new Jewish Museum London opened in a refurbished former factory in Camden Town.

In 2015, the Jewish Museum joined forces with the Jewish Military Museum to host and share its heritage. Personal stories of Jewish Crown soldiers, their letters, literary and artistic creations, medals, and objects of worship are available.

The Jewish Museum also presents the story of Leon Greenman, a Holocaust survivor who fought for the sharing of the memory of the Holocaust, and was involved in many school programs until his death in 2008. In a room provided by the museum for the sharing of this memory, there are also other recorded survivor testimonies.

Since 2023, the Jewish Museum London has been operating outside its walls while work is underway to create a new permanent site.

Other Jewish institutions of London

The Jewish Museum has two buildings, one in Camden and the other in Finchley. Founded in 1832, the museum in Camden houses the world’s finest collection of religious and other objects, many of them brought by immigrants from the Norman Conquest to more recent times. Particularly notable are the eighteenth-century portraits, an interactive map showing population movements in Great Britain, an Italian aron from the sixteenth century, the oldest Hannukah lamp in England, and illuminated marriage contracts.

The Sternberg Centre for Judaism , located in the London Borough of Finchley, is a community centre hosting many Jewish institutions, many of them from the Liberal and Masorti movements. It is named after the philanthropist Sigmund Sternberg.

It was inaugurated in 1981. Among the institutions it oversees are the Akiva School, the New North London Synagogue and the Leo Baeck College, named after the famous rabbi. Founded after the war, this training centre, inaugurated in 1956, became a leading training centre for liberal rabbis and in 1975 ordained its first woman rabbi, Jacqueline Tabick. Until 2007, it hosted one of the two sites of the Jewish Museum in London.

Opening of synagogues in new areas

The migration of London Jews from the centre to the north encouraged the opening of synagogues in different neighborhouds.

Opened in 1876, the synagogue of St John’s Wood benefited from the geographical development that motivated Jews to move beyond the East End. A community centre in 1957 and a synagogue seven years later brought more people to Grove End Road. Note its beautiful stained glass windows by David Hillman.

At the end of the 19th century, as the Jewish population gradually left the East End, some moved to Hampstead. Several associations came together to create a synagogue that would follow the German and Polish rites. The Hampstead Synagogue was built in 1892.

The second major Sephardic synagogue founded after Bevis Marks, the Lauderdale Road Synagogue served the Jewish community in the west. It was inaugurated in 1896 in the Byzantine style. Among its great leaders was Rabbi Solomon Gaon. The synagogue welcomed Nathan Saatchi on his arrival, father of the famous advertisers and active donors to the community.

This Orthodox synagogue of Golders Green was founded in 1915. The arrival of many Jewish families over the years led to the development of educational and cultural institutions within the synagogue. The development of the railway beyond Golders Green in 1924 and the changing demographics led to the arrival of Jews in the Edgware area. The Edgware United Synagogue was built in 1934.

In the late 1920s, a group of Jewish residents of Wembley expressed a desire to establish a place of worship in the area. The Wembley Synagogue was founded in 1934. As the Jewish presence in the area grew, an extension to the synagogue was built in 1956.

Development of various Jewish movements

Founded in 1964 and led by Rabbi Louis Jacobs following famous debates on biblical interpretation, the New London Synagogue is today a major centre for the Masorti movement. Its rabbis are very involved in contemporary social debates.

Better known as the Kinloss Synagogue, the Orthodox Finchley United Synagogue was opened in 1967. It can accommodate over 1400 people and offers many cultural and associative events. A Persian Rite synagogue is also located inside the building.

Among the Jewish cemeteries in North London, the main ones are Hoop Lane Cemetery and Willesden Jewish Cemetery (opened in 1873 and containing over 20,000 graves).

Of the Jewish presence in the City during the Middle Ages, there remains little more than memories, but it is a pleasure to walk around here. The three streets around the Bank of England -Poultry, Cheapside, and Old Jewry- were home to a community before the expulsion of 1290.

Jewry street, near Aldgate Underground station, is where the Jews took refuge during the riots that broke out at the coronation of King Richard I in 1189. And in Creechurch Lane the Cunard building marks the spot where the first synagogue was built in London after Cromwell’s decision to allow Jews back onto English soil.

Bevis Marks frequented by Disraeli and Montefiore

Still close to Aldgate Underground station, up Duke’s Place, we come to Bevis Marks Synagogue , which was built in 1701 by the Portuguese and Spanish Jews after the return of the Jews from 1655 onward. The synagogue was located within the city walls, and its site was chosen so that it would not be visible from the street because the community wanted to remain discreet.

Extremely well preserved, it is one of the oldest and most handsome synagogues still in use in Great Britain today. It also has a rich history, having been frequented by Sir Moses Montefiore and Benjamin Disraeli and because of its links with the Rothschild family. In addition, it houses one of the finest sets of pews from the Cromwellian and Queen Ann periods. The interior was strongly influenced by the mother synagogue in Amsterdam, which indeed donated one of the candelabras.

Jewish life near the docks

The East End has a long tradition of immigration. Located close to London’s docklands, it welcomed Huguenots and Irish immigrants and, after them, Jews. Today, its population is mainly made up of immigrants from India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh. This evolution is amusingly embodied in the history of the gloomy building on the corner of Fournier Street and Brick Lane: originally a Huguenot church, it later became a synagogue and is now a mosque. Before World War II, some 100,000 Jews lived here. There are now only 6,000. To get an idea of the old days, read Israel Zangwill (1864-1926), called the “Jewish Dickens”. Zangwill paints a highly enjoyable and marvelously vivid picture of Jewish daily life here during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

The synagogue on Princelet Street is a real treasure. Built in 1870 on the foundation of an old Huguenot house dating from 1709. It was closed in 2020. In the area still, you’ll find the Dutch Synagogue on Sandy’s Row , installed in a Huguenot chapel of 1766.

Promenades in the West End’s quarters and gardens

The West End of London also has plenty to satisfy visitors’ curiosity. The history of British Zionism reminds us that Chaim Weitzman and other Zionists used to meet at 17 Piccadilly, which is also where Lord Rothschild received Lord Balfour’s famous letter on 2 November 1917. Hyde Park has a small garden laid out in 1983 in memory of the Shoah.

The New West End Synagogue is one of London’s finest. The first stone was laid on 7 June 1877 by Leopold de Rothschild, and the synagogue opened on 30 March 1879. It is similar in appearance to the Princes Road Synagogue in Liverpool. Both were built around the same time by the same architect, George Audsley. There are fine stained-glass windows, as well as twenty Sifrei torah, embroidery, and silverware from the early eighteenth century.

The synagogue on Great Portland Street, also known as the Central Synagogue , was built on the site of London’s first Ashkenazic synagogue, consecrated in 1870. It was destroyed by a German bomb on 10 May 1941 and rebuilt in 1958. This modern structure has twenty-six stained-glass windows illustrating the Jewish festivals.

The historical synagogues of Westminster, Marble Arch and Western

The very handsome Westminster Synagogue , close to Harrods, has a unique collection of 1000 Torah scrolls. Confiscated by the Nazis in Bohemia and Moravia, the scrolls were transported to London in 1964. They can be viewed on request.

The Marble Arch Synagogue represents the union of two places of worship: the Western Synagogue (founded in 1761) and the Marble Arch Synagogue (1957). The Western was the first to be built outside the City. And the first one where sermons were held in English. This union came into being in 1991. One of its former rabbis was Jonathan Sacks.

About twenty Jews who had moved to the West End met in 1840 to find a place to worship. The first synagogue, opened in 1842, was in Burton Street. It moved to Upper Berkeley Street in 1870. The West London Synagogue is part of the Reform movement and has about 3000 members and many cultural activities.

The precious documents of the Imperial War Museum

On the other side of the Thames, the Holocaust Museum is housed in the Imperial War Museum . Among the surprising objects on display here are a cart from the Warsaw Ghetto that was used to carry corpses and a railway car used in the deportation (a donation from the Belgian railways authority). Also worth a mention for its originality is the exhibit showing how Jews have contributed to Her Majesty’s Army from the Crimea through to the present.

Among the Jewish cemeteries in the center of London, the main ones are Alderney Road Cemetery (the oldest Ashkenazi cemetery, used from 1697 to 1852), Brady Street Cemetery and the Novo Cemetery (one of the oldest traces of Jewish presence in London).

“Here is buried the body of Sieur Salomon de Perpignan, one of the founders of the Free Royal Drawing School established in the year 1767 of the glorious reign of Louis XV in the city of Paris…Died 22 February 1781”. These are the words on one of the oldest tomb in Paris’s Jewish cemetery. They give an idea of the social importance acquired by the “Portuguese” Jews of Paris in the eighteenth century, even though they were only “tolerated” as an exception to the expulsion edict, which was still in force.

This small plot of land was bought on 3 March 1780 by Jacob Rodrigue Pereire, an “agent of the Portuguese-Jewish nation in Paris”. The legality of the cemetery was recognized in an edict that allowed Jews to be buried there “at night, without noise, scandal, or ceremony, in the accustomed manner”. The cemetery was closed in 1810, when Père Lachaise opened a special area for Jewish sepulchers. It now lied hemmed in between the tall buildings of this modern quarter.

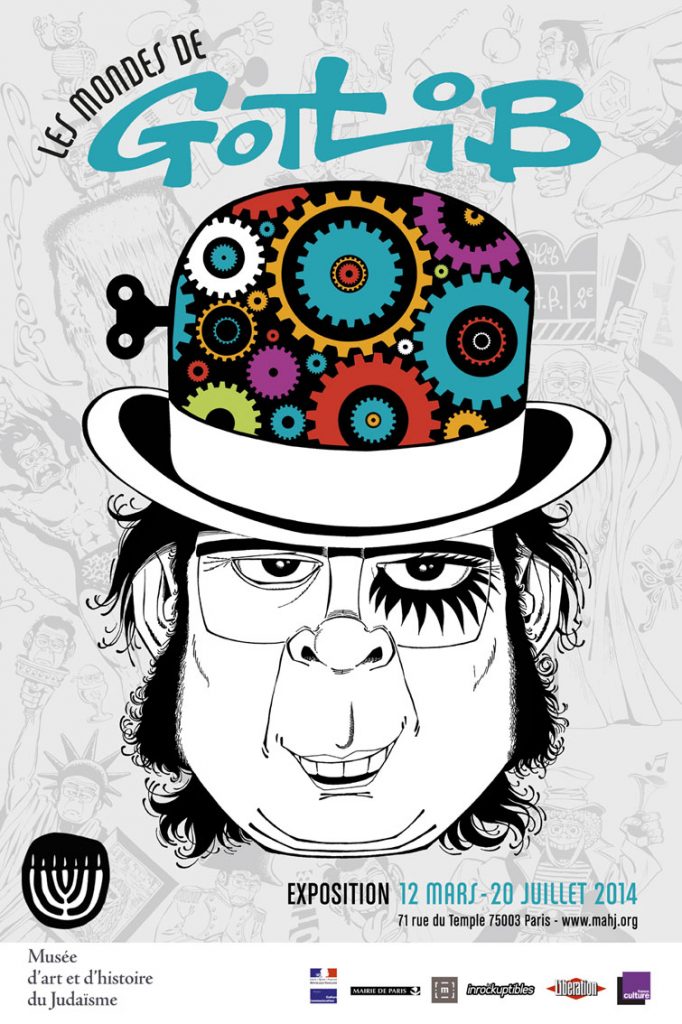

Many Jews lived in the artistic neighborhood of Montmartre before the war. Among them, the families of artist Marcel Gotlib and writer Joseph Joffo. A beautiful synagogue is still there today.

In addition to its architecture and activities, the Opéra de Paris (or Palais Garnier) is notable for its extraordinary ceiling painted by Marc Chagall in 1964.

Not far from here, in a room at Hôtel de Castille (37 rue Cambon), Theodor Herzl wrote The Jewish State. This was the founding work of political Zionism, which bore fruit some fifty years later in the proclamation of the State of Israel.

The synagogue on rue de la Victoire is the biggest in Paris. This is where the Jewish community’s official ceremonies are held. Consecrated on September 9 1974, it was, according to the original design, supposed to to have an entrance on rue Ollivier (today’s rue de Châteaudun). However, on the advice of her confessor, Mgr. Bernard Bauer, a Hungarian of Jewish origin, Empress Eugénie opposed this idea: the Grande Synagogue de Paris must not open onto a main thoroughfare !

The synagogue was built to plans by the head architect of the City of Paris, Adrolphe, who was himself a Jew. The overall conception is a rather florid Romanesque, with Moorish echoes. Outside, the main facade is forty-three yards high. On it, the Hebrew inscription under the two Tablets of the Law reads: “My house shall be called the house of prayer for all peoples”. Inside, the large prayer hall and the five arches are flanked by two galleries. The upper gallery was designed purely for architectural effect. Nowadays, though, it can be used to hold worshippers during major celebrations, this increasing the synagogue’s capacity.

The building, which is thirty-four yards high to the keystone, is fifty-two yards long and thirty-three wide. Its only decoration is twelve stained-glass windows by Lusson, Lefèvre, and Oudinot representing the symbols of the biblical Twelve Tribes.

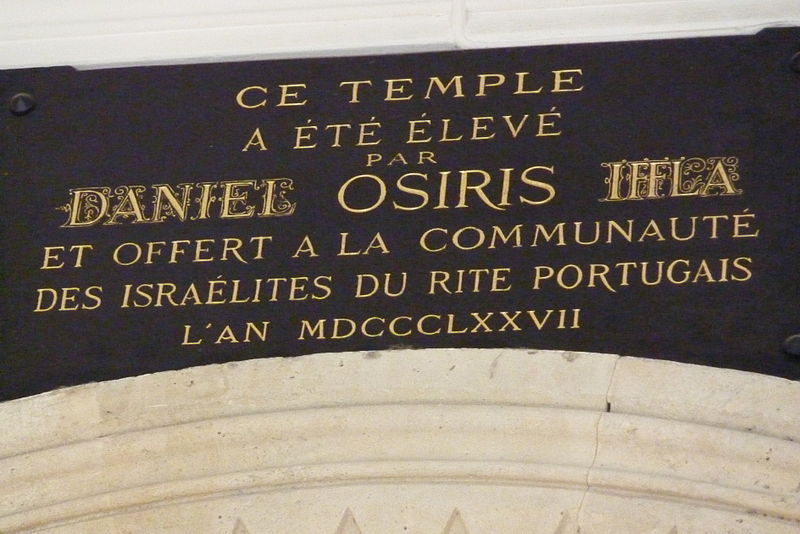

In 1874 the leaders of the Portuguese Jewish community refused the fusion of Sephardic and Ashkenazic rites and, at the same time, decided to build their own temple. To this end, a non-trading stockholders’ company was set up by Jews from Bayonne, Comtat Venaissin, and the Ottoman Empire with a view to buying land and financing construction.

The architect Stanislas Ferrand was entrusted with the design. The resulting synagogue , on rue Buffault, was consecrated on 3 September 1877. The facade is twenty eight yards high. On it, the following lines from Deuteronomy are written in Hebrew: “Blessed are you when you come in, and blessed are you when you go out”.

Inside, the gallery is supported by six marble columns. The arches around the keystone form the Tablets of the Law and have biblical names inscribed on them.

At the center of the prayer hall, a large seven-branch candelabrum stands on the altar. To the rear, a large staircase with a wrought iron balustrade leads to the cupboard that houses the Torah scrolls. Above the cupboard, emerging from sculpted stone clouds, are the Tablets of the Law.

The Tsarphat

During the early planning stage in 1850, the synagogue on rue de la Victoire was intended to house a unique French rite, the Tsarphat, a single liturgy combining Portuguese chants and Alsatian pronunciation. This generous idea caused no end of debate. In 1866, a report by the consistory noted that ‘The construction of the temple on rue de la Victoire will make it possible to fulfill the oft-expressed wishes of our coreligionists from the German rite and the Portuguese rite, namely to meet in a shared-sanctuary, in a word to establish there a unified rite that is so desirable in every way”.

The war with Prussia in 1870 delayed the project. Finally, on 17 May 1874, Zadoc Kahn, the grand rabbi of France, brought together 150 Sephardic notables, who, after a debate, firmly rejected the idea. The synagogue on rue de la Victoire would thus become an Ashkenazic temple. However prayers were still spoken “in the oriental manner” for another fifteen years; they had not given up all hope of fusion.

At the beginning of the twentieth century, the legendary bohemia of Montparnasse included many Russians Jewish painters who had fled the anti-Semitic pogroms of the day. Among them were Soutine, Chagall, and Zadkine. Others, such as Modigliani, were simply attracted by the city’s prestige and contributed to the tremendous creative effervescence of the day.

These inspired individuals, spurred on by these emancipations, settled in Paris at the beginning of the 20th century. By confronting and sharing their art thanks to the French sculptor Alfred Boucher, who wanted to bring together young artists without resources to work in a fraternal spirit. A former rotunda from the 1900 Universal Exhibition, with 200 studios. A city within a city, it brought together Fernand Léger, Marie Laurencin, Matisse, Soutine, Modigliani, Chagall and Douanier Rousseau, as well as writers Apollinaire, Tchekov and Max Jacob.

Among them were many Jewish artists fleeing the pogroms and quotas to settle in Paris. There, to see Expo 1900, its museums, salons and the development of the art market with its galleries. Boucher nicknamed his artists ‘his bees’, hence the building’s nickname: the Beehive .

This gave rise to the term ‘Paris School’, referring to the non-French artists who took part in this artistic encounter between these artists and the muse city. With this willingness to look inside and outside themselves. And the appearance of extras, figurines of childhood in their works, these characters always so touching and so distant from their childhood, removed by the twists and turns of History, like the violinist on a roof in a painting by Chagall, cheering up the shtetl.

Division 22 of the Montparnasse cemetery is the resting place of the painter Jules Pascin, one of the “artistes maudits” who lived out his wild, nocturnal life in this quarter. Born in Bulgaria in 1885, he committed suicide in Paris in 1930.

A drawing engraved on his tombstone evokes his work, accompanied by the words: “A free man, hero of dreams and desire, opening the golden doors with his bleeding hands, flesh and blood, Pascin disdained to choose and, master of life, ordained his own death.” A little further on, in Division 28, a white stone bears the name of the officer Alfred Dreyfus (1859-1935). Here lies the man who was wrongly accused of high treason, of betraying French military secrets to Germany.

West of Montparnasse, near the avenue de Ségur, curious travellers will make a point of visiting what older Parisians consider to be one of the capital’s most handsome and original synagogues. The Chasseloup-Laubat synagogue. , consecrated on September 29 1913, was designed by the architect Bechmann. The square hall has sides fifteen yards long. The gallery is supported by wooden columns that rise all the way to the octagonal wooden dome of the roof.

The synagogue JEM Beaugrenelle , part of the liberal Judaïsme En Mouvement (JEM) offers one of the most original modern architectural creations. It is located at the movement’s Community center which also hosts a reception hall and classes, inaugurated in 1980 by Rabbi Daniel Farhi. The building is covered with ceramic tiles and is visible from two streets superposed.

The interiors of the synagogue are quite sober, using mostly wood and Hebrew scriptures. Rabbi Delphine Horvilleur participates in numerous contemporary national debates and projects, having been after Pauline Bebe the second nominated woman rabbi. The movement has since been joined by other men and women rabbis.

The Massorti movement appeared in France in the 1980s. Several Massorti communities are present in Paris. The largest being that of Adath Shalom , headed by Rabbi Rivon Krygier. The presence and contemporary development explains the modernity of the synagogues welcoming the liberal and massorti movements. The one where Rivon Krygier officiates is located rue George Bernard Shaw, in the 15th arrondissement. A district that harmoniously hosts three important synagogues of Parisian life, each linked to a movement.

Talking about moving, many steps, images and sounds whirl around the stage of the Rachi – Guy de Rothschild Center which welcomes many events related to Jewish culture in its big auditorium. Among them concerts, conferences and major annual events such as the Jazz n’Klezmer Festival with artists from all over the world sharing the stage here and all around France and the Diasporama Festival dedicated to Jewish themed movies tackling all types of subjects.

Movements are a big part of music. Created in 2006, the European Institute of Jewish Music is dedicated to collecting, preserving and disseminating Jewish musical heritage in France and abroad. On stage, Guy Bedos spoke of the diversity of Jewish cultural expression, pointing out that for Enrico Macias, what Serge Gainsbourg sang was probably not quite Hebrew. It’s this diversity of places, times, styles and eras that you’ll discover at the IEMJ, whose website features numerous playlists, radio and TV broadcasts and concerts. Wishing you a pleasant musical journey.

In the eighteenth century, the area around the Place Saint Paul was known as “the old Jewry”. Until the first years of the twentieth century, the square itself bore the name Place des Juifs. The narrow streets here are best explored on a Sunday morning, when everyday Jewish life has resumed after the Shabbat.

Rue Pavée is a few yards from the Saint Paul métro station. This is the pletzel, which is yiddish for small square. In this street, which runs perpendicular to rue des Rosiers, stands a surprising registered historical building in the “nouille” (noodle) style. This is the Pavée synagogue designed in 1913 by Hector Guimard, then the leading exponent of Art Nouveau, who is responsible for Paris famous métro entrances.

Jews have lived on rue des Rosiers since the middle ages. When Charles VI expelled them from his kingdom, the street fell empty -or so it seemed. That the newly emancipated Jews came back in this same street after the French Revolution, some 400 years later, had led historians to suggest that Jewish families went on living here in secret during the intervening centuries. Thus, when the edict was revoked, it was natural for many of the returning Jews to join fellow believers.

In all likelihood an oratory was built on the upper floor at 17 rue des Rosiers a few years before the French Revolution. Unfortunately, the relevant archives were destroyed during the Nazi occupation. Rue des Rosiers 10 leads to the Rosiers – Joseph Migneret garden , located between several buildings, named in honour of the teacher and headmaster of the Hospitalières Saint-Gervais primary schools (located in one of the buildings surrounding the garden) who saved Jewish children during the Holocaust.

Today, in spite of its many luxury stores, rue des Rosiers remains an important center of Parisian Jewish life with its bookstores, especially the Temple Bookstore , the main reference with the mahJ’s library for books concerning Judaica.

Once a major center for Eastern European Jewish gastronomy, with the Goldenberg restaurant in particular, the Florence Kahn and Sacha Finkelsztajn delicatessens are still very popular, particularly for their Ashkenazi dishes, haloth and pastries. Since the early 2000s, other Jewish specialities have been delighting tourists. These include L’As du falafel and Schwartz’s with its New York-style pastrami sandwiches. For lovers of Israeli cuisine and its famous pita bread, don’t miss Miznon, designed by the famous chef Eyal Shani. The menu features spicy fish, ratatouille and homemade cauliflower in a warm, relaxed atmosphere. But also the Café des Psaumes, bringing together different generations of enthusiasts of the Pletzl atmosphere around conferences, concerts, workshops and courses. A plaque has been placed over the entrance to the former Goldenberg restaurant in tribute to the victims of the terrorist attack on 9 August 1982.

Many Jewish moneylenders lived on rue des Écouffes. In old French, escouffe was the word for a bird of prey, the kite, which was the symbol for pawnbrokers. The street name thus recalls the financial professions to which Jews were limited by the authorities. Until the beginning of the twentieth century, rue Ferdinand Duval was called “rue des Juifs” (Street of the Jews). Realizing that this moniker might be offensive, City Hall renamed it Ferdinand Duval, after a prefect of Paris.

On rue du Temple, you will find Galerie Saphir, founded in 1979 by Francine Szapiro, a journalist with a passion for art, and her husband, a doctor and founding member of the French Commission for Jewish Archives. At a time of Jewish cultural reconstruction, they shared the dream of opening a gallery that would showcase all aspects of this culture, its manifestations, ritual objects and ancient books… without confining it to a ghetto, motivated by the desire to show the reciprocal contribution of the surrounding cultures.

Their first gallery was on the boulevard Saint-Germain, and was opened by Elie Wiesel with an exhibition on postcards and Judaism designed to show the diversity of the Jewish world. They then began exhibiting Alain Kleinmann, then Shelomo Selinger. Then they moved to the current gallery.

Right next door to the gallery, on the same rue du Temple, is the unmissable mahJ, inaugurated in 1998.

The Hôtel de Saint Aignan, a superb seventeenth century mansion, now houses the Museum of Jewish Art and History (Musée d’Art et d’Histoire du Judaïsme) remarkable both for its collections and for its ambition. The museum is the fruit of a three way cooperation between the City of Paris, the Culture Ministry and community institutions.

The museum is based on a collection assembled in the 19th century by the conductor Isaac Strauss. Like his Viennese namesakes, the French Strauss composed waltzes and got society dancing during the Second Empire. His success soon spread beyond France’s borders, and his passion for Jewish history led him to collect ritual objects from all periods during his travels around Europe. In 1890, this remarkable collection was acquired by Baroness Nathaniel de Rothschild, who donated it to the State. The museum also brings together objects that were long on display at the Museum of Jewish Art – now closed – opened after the war in Montmartre (wooden models of Polish synagogues made after the war by students at the ORT vocational school), the collections of the Consistoire of Paris (Torah crown, Galicia, 1810) and those of the Fondation du judaïsme français, as well as its own acquisitions (painting by Samuel Hirszenberg, The Jewish Cemetery, 1892).

The visit starts on the first floor with the fundamental texts and symbolic objects. The rooms that follow reveal the diverse facets of Judaism. The medieval Jewries are represented by tombstones discovered in the nineteenth century when boulevard Saint Germain was built. Italy and its ghettos are represented by liturgical furniture (a circumcision chair [Kisei shel Eliyahu] from the early eighteenth century), silverware, and embroidery. Amsterdam, London and Bordeaux are evoked by objects and prints (a painting by Jean Lubin Vauzelle of the synagogue at Bordeaux, 1812) that exemplify integration of the Jews cast out of Spain. Considerable space is devoted as well to the celebrations that punctuate the Jewish year: Purim rolls, Hannukah lamps, a nineteenth century Austrian sukkah decorated with a view of Jerusalem.

Two sections, the Traditional Ashkenazic World and the Traditional Sephardic World, offer overall artistic and religious views of these two main ritual communities. A sequence entitled “Emancipation: The French model” offers a historical vision from the French Revolution onward (an 1867 painting by Edouard Moyse shows the Great Sanhedrin of Paris), highlighting key moments of integration. The Jewish presence in twentieth century art presents works from the early decades of the last century. Underlying these runs the eternal question of Jewish expression in art through folklore, ornament, biblical sources and calligraphy.

The evocation of the Shoah is intended as a memorial, a pause in the itinerary. Finally, temporary exhibition rooms open to contemporary artists, an auditorium for concerts, lectures and screenings, a library, a photo library, a video library and a tea room complete this impressive ensemble.

Our interview with Paul Salmona, Director of the mahJ, who tells us about the history of the museum and its great moments, as well as the its future projects.

Jguideeurope: What is the origin of the choice of place to host the mahJ?

Paul Salmona: The idea of a museum of Judaism in Paris is quite old, but it crystallized in 1980 with the exhibition at the Grand Palais of masterpieces from the Jewish collection of the Musée de Cluny. The project then took shape with the search for a place. Claude-Gérard Marcus, an elected official from Paris, convinced Jacques Chirac to make the Saint-Aignan hotel available, acquired by the city in 1962 as part of the Marais safeguard plan. At the same time, Jack Lang undertook to co-finance the project and to deposit the Cluny collection there. A prefiguration association was created in 1988 and ten years later the museum opened under the aegis of Laurence Sigal, the first director. It made sense to install it in this aristocratic palace occupied from the 19th century by workshops of furriers, tailors, cap makers and hatters, halfway between the rue des Rosiers and the synagogue of Nazareth, in a neighborhood which welcomed waves of Jewish immigration from eastern France, then central and eastern Europe. A work by Christian Boltanski recalls this story in a work entitled “The Inhabitants of the Hôtel de Saint-Aignan from 1939” and installed in a courtyard.

Can you tell us about some particularly striking moments in the mahJ?

There are so many in 22 years of intense activity. Among the acquisitions, mention should be made of the donation of the 2,600 archives of the Dreyfus affair by the captain’s family, or the purchase in 1988 of the Austrian soukkah, Laurence Sigal’s first acquisition against payment; we can mention the gift of the Columns of Guerry by Georges Jeanclos by the artist’s family, the purchase of 435 old photographs by Helmar Lerski thanks to a public subscription… Before taking up my post, I was very marked by the he exhibition “Future Futur” which revealed to the French public the avant-garde of the years 1914-1939 which aspired to create a truly Jewish modern art by drawing on the traditional folk art of Yiddishsland. Another example is the Golem Exhibit, which showed how this myth permeates the West even though few people know that it was originally a Jewish legend. The Charlotte Salomon exhibition was a real discovery for the public, which had as its posterity the reissue of Vie? Ou théaâre? by Le Tripode, a huge success for an art book of this ambition. I am also thinking of the self-portraits of Arnold Schönberg, which were little known and whose exhibition made a big impression on the public. The mahJ has also given a good place to the 9th art with “From Superman to the Rabbi’s Cat” and “The worlds of Gotlib” or “René Goscinny, beyond laughter”.

Can you think of another place related to Jewish cultural heritage that is important to you personally and that deserves to be better known?

I am thinking first of the synagogue of Cavaillon, built in the middle of the 18th century on the site of the medieval synagogue. Very rococo style, it is well highlighted by its recent restoration. It is the witness of a vanished world, that of the Comtadin Jews, which had survived the medieval expulsions but disappeared with the Emancipation and the departure of these rural elites to the big cities. I am also thinking of the medieval Jewish monument of Rouen, discovered by chance in the courtyard of the Palais de Justice in 1976. It is the oldest Jewish archaeological remains in elevation, dating from the end of the 11th – beginning of the 12th, whose architecture has the same qualities as those of contemporary Romanesque churches. After the discovery, it had been covered by a hideous slab of concrete, hampering its conservation and complicating its visit. It is a place that bears witness to the importance of the Jewish presence in France before the expulsions of the late 14th century. It is also located rue aux Juifs, a toponym that recalls the central place of Jews in cities in the Middle Ages in France. Recent archaeological research tends to show that this building was a synagogue. Benches were found on the first floor with a “header” stone at the bottom which probably supported the holy ark.

We were previously talking about these disappearing places of Jewish cultural heritage. Conversely, the mahJ has an expansion project. Can you tell us more?

The mahJ currently has a permanent course of 1000 m² dating from the 1990s, which is insufficient. We have an ambitious but realistic extension project under the Anne Frank Garden. It will make it possible to gain 1,000 m², and create rooms of 550 m² for temporary exhibitions. As for the current temporary exhibition rooms, they will allow the permanent exhibition to be extended to an additional 400 m². The route will start with the Jewish presence in France in Antiquity (essential for schoolchildren) and will continue with the height of Franco-Judaism in the interwar period, the rescue of the Jews during the Occupation, the reconstruction of Judaism in France after 1945 and the contemporary collection. It is an 18 M € project which benefits from the financial support of the city of Paris and the State for two thirds. We are therefore looking for € 6 million from private donors. We hope to open in 2025 in a completely renewed museum.

As you walk toward the Place des Vosges, you’ll find on this beautiful place the Charles Liché Synagogue , built in 1963 and named after its founder and rabbi.

One street behind, there is the Synagogue on rue des Tournelles . The original building, from 1861, was burned down during the Paris Commune of 1871. It was rebuilt following a design by Marcellin Varcollier in a style close to that of the synagogue on rue de la Victoire.

The facade features the Tablets of the Law and the Paris city coats of arms. Consecrated in 1876, this synagogue has a visible metal inner structure built in the workshops of Gustave Eiffel more than ten years before his famous Tower. The two rows of galleries, made entirely of iron and cast iron, provide both support and ornament.

The sculptures on the Saint Anne portal of Notre Dame Cathedral offer one of the most moving testimonies we have to medieval Judaism.

The frieze in question, just above the doorway, dates from the late twelfth century. It represents the Virgin’s mother, Saint Anne, meeting her future husband, Saint Joachim. The unknown artist used Parisian Jews as his models in order to represent these early Christians. The men have the long robes and pointed hats worn by Jews in medieval times.

The left-hand side illustrates Anne and Joachim’s wedding. Wrapped in his prayer shawl, the rabbi stands between the betrothed, whom he takes by the hand. All the details here evoke the atmosphere of a Parisian synagogue. The artist has painstakingly sculpted the arks, the eternal lamp, and the piles of books that are so characteristic of Jewish life.

The iconography in the center is purely Christian: an angel announces the coming birth of Mary to the barren couple.

On the right, Anne and Joachim are taking their offerings to the synagogue. On the altar is a Torah scroll. The end of the frieze depicts two Jews in conversation. These stone figures convey images of Judaism from ancient times.

On the two central buttresses on the main facade, notice the niche on the right housing The Vanquished Synagogue, an allegorical statue by Fromanger depicting the eyes covered by a snake, a broken scepter, and crown trodden underfoot.

The pendant statue on the left is The Church Triumphant by Geoffroy Dechaume. These sculptures were made during the restoration work undertaken by Viollet le Duc in the nineteenth century, replacing the original sculptures destroyed during the Revolution.

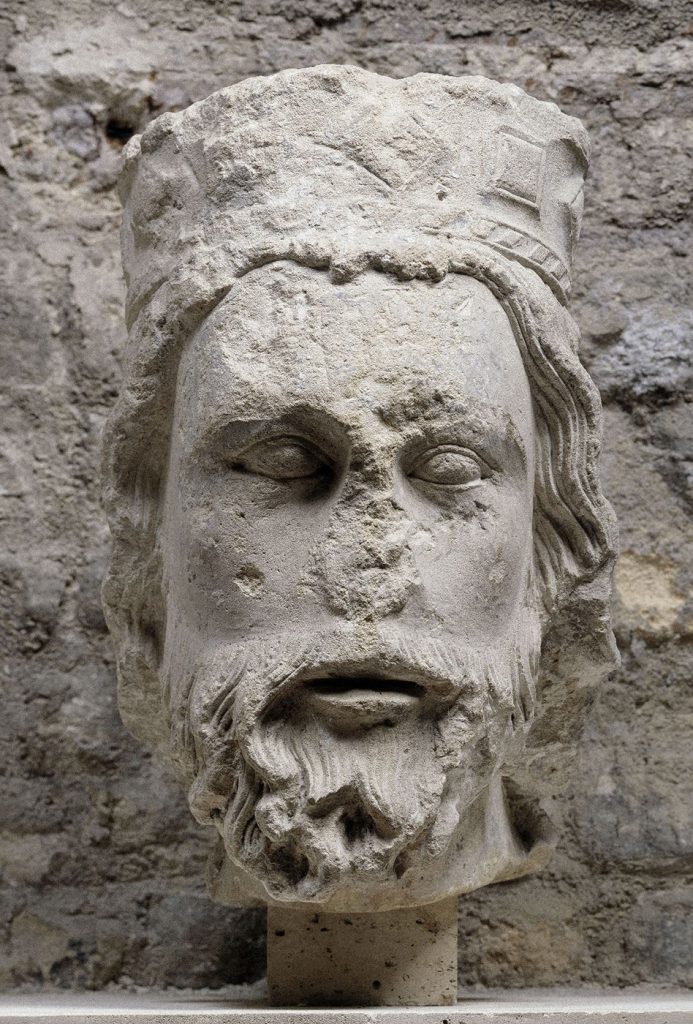

Just above them, the Gallery of Kings represents twenty-eight kings of Judah and Israel who, according to Christian tradition, were the ancestors of Jesus. In 1977, 364 fragments of sculptures from Notre Dame that had been smashed during the Revolution were found during work on rue de la Chaussée d’Antin. Although no traces of the Vanquished Synagogue were found, twenty one of the twenty eight heads of the kings of Judah and Israel were discovered. These are on display at the Cluny Museum (Musée national du Moyen Âge des Thermes de Cluny).