The history of the Jews in Cologne is documented from the year 321 AD, almost as long as the history of Cologne. Over its history, the Jewish community of Cologne has suffered persecutions, many expulsions, massacres and destruction. The community numbered about 19,500 people before its dispersal, murders and destruction in the 1930s by the Nazis before and during World War II. The community has re-established itself and now numbers about 4,500 members. Because of its historical continuity, today’s Jewish synagogue calls itself the “oldest Jewish congregation north of the Alps”.

2000 years of Jewish history

Cologne was founded and established in the 1st century AD and it is reasonable to assume that the spread of Christianity in any Roman province was preceded and accompanied by the existence there of Jews. The presence of Christians in Cologne in the 2nd century would therefore argue for the settlement of Jews in the city at that early date. Judaism was recognized as a religio licita (permitted religion). In 321, a decree of Emperor Constantine the Great of 321, permits Jews to be appointed to the curia. In another document, from 341, it is recorded that the synagogue was provided with the emperor’s privilege. These decrees of Constantine remained for some centuries the only accounts of the existence of a Jewish community in Cologne.

During the Middle Ages, Cologne flourished as one of the most important trade routes between east and west Europe. The first documentary reference to the Jews in Cologne in the Middle Ages was in 1426 when a report mentions a 414 year old synagogue turned into a church. The number of Jews in the community during the last quarter of the 11th century was not less than 600. The markets of Cologne had attracted many Jewish visitors who had partly stayed. Italian Jews are mentioned in the stories about the Crusaders in Cologne.

Persecutions and pogroms

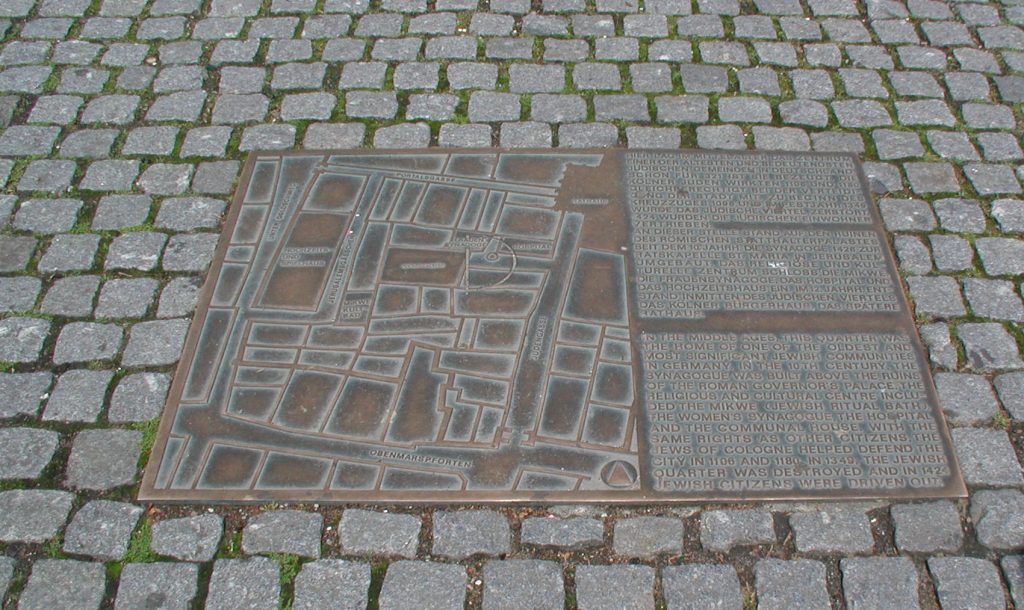

During the Middle Ages, the Jewish community had been settled in a quarter near the Rathaus. Still now the name “Judengasse” testifies its existence. During the First Crusade in 1096 there were several pogroms. On 27 May 1096, hundreds of Jews were killed in Mainz during the Rhineland massacres. A similar thing happened in July of the same year in Cologne. The Jews were forcibly baptized. The permission of Emperor Henry IV to let the Jews who had been forcibly baptized go back to their faith was not ratified by Antipope Clement III. During the Second Crusade, it seems that the Jews of Cologne were somehow spared.

An early pogrom against had taken place after the Battle of Worringen on 8 June 1288. For days afterwards a persecution of Jews swept through the surroundings of Cologne. In 1300, a wall was built around the Jewish Quarter, presumably paid for by the Jewish Community itself.

In the course of St. Bartholomew’s Night in 1349 the Jewish quarter near the town-hall (Rathaus) was attacked, after which killing, plundering of Jewish properties, and arson followed. In its escape from the riot one family buried its belongings and merchandise. The hoard of coins was discovered during excavations in 1954 and is now exhibited in the Kölnisches Stadtmuseum .

The Jews of Köln seemed, according to documents, to have returned only in 1369, although a small community was documented beforehand.

There is proof that by 1372 a small Jewish community had again sprung up in Cologne. At the request of Archbishop Frederick, the Jews were admitted to the town and obtained a temporary protection privilege for ten years. To this, however, the Council attached some conditions. For the privilege of admission there was a tax . After further extensions of the right of residence the Council proclaimed in 1404 a more restrictive Judenordnung. It ordained that the Jews had to be recognizable by wearing a pointed Jewish hat and banned any displays of luxury on their part. In 1423 the Cologne Council decided not to extend the temporary right of residence, which expired on October 1424.

Spitirual and intellectual development

In 1424, Jews were banned from the town “for eternity”. Following the medieval pogroms and expulsion of 1424, many Jews of Cologne emigrated to central or northern European countries like Poland and Lithuania. The offspring of these emigrants returned to Cologne at the beginning of the 19th century and lived mainly in the area of Thieboldsgasse on the southeast side of Neumarkt. Only a few Jews remained near Cologne and settled predominantly on the eastern bank of the Rhine (Deutz, Mühlheim, Zündorf). Later new communities developed, which grew over the years. The first community in Deutz lived in the area of the present Minden Street (“Mindener Straße”).

After the destruction of the community during Second World War, the medieval foundations were discovered, among them a synagogue and the monumental Cologne mikveh (ritual bath). The archeological survey was conducted after the war by Otto Doppelfeld from 1953 to 1956. On the basis of the awareness of history the area has not been reconstructed after the war and has remained as a square in front of the historical Rathaus. Today, the Jewish quarter is part of the Archeological zone of Cologne.

In Cologne there was one of the largest Jewish library of Middle Ages. After the massacre of the Jews in York, England in 1190, a number of Hebrew books from there were brought to and sold in Cologne. There are a number of remarkable manuscripts and illuminations prepared by and for Jews of Cologne during the 12th to the 15th centuries and now kept in various libraries and museums throughout the world. Cologne was as well a center of Jewish learning, and the “wise of Cologne” are frequently mentioned in rabbinical literature. A characteristic of the Talmudic authorities of that city was their liberality. Many liturgical poems still in the Ashkenazic ritual were composed by poets of Cologne.

The Jewish cemetery of Cologne is mentioned in 1906 and was of a size of about 30000 m2. The eldest tombstone found to this day is from 1152.

Right-Rhenish Deutz and its Jewish quarter

After the expulsion, the few Jews who remained in the city, began to re-establish a community in right-Rhenish Deutz, today part of Cologne. In 1634, there were 17 Jews in Deutz, in 1659 there were 24 houses inhabited by Jews and in 1764 the community consisted of 19 people. Towards the end of the 18th century the community still consisted of 19 people. The community was located in a small Jewish “quarter” in the area of Mindener and Hallenstraße. A synagogue, first mentioned in 1426, was damaged by the immense ice drift of the Rhine in 1784. The mikveh associated with the synagogue probably still exists under the embankment of the Brückenrampe (Deutzer Bridge). This first synagogue was then replaced by a new small building on the west end of “Freiheit”, the today’s street “Deutzer Freiheit” (1786–1914).

The history of the Jewish communities outside the city center is revealed above all through the remains of the Jewish cemeteries. There are right-Rhenish Jewish cemetery in Mülheim, in Zündorf , and one in Deutz. The latter was given to the Jews of Deutz by Archbishop Joseph Clemens of Bavaria in 1695 as a rented land. The first burials in the Jewish cemetery of Deutz took place in 1699. When in 1798 the Jews were again permitted to settle within the old city walls of Cologne, the cemetery was also used by this community until 1918.

Synagogues in Cologne

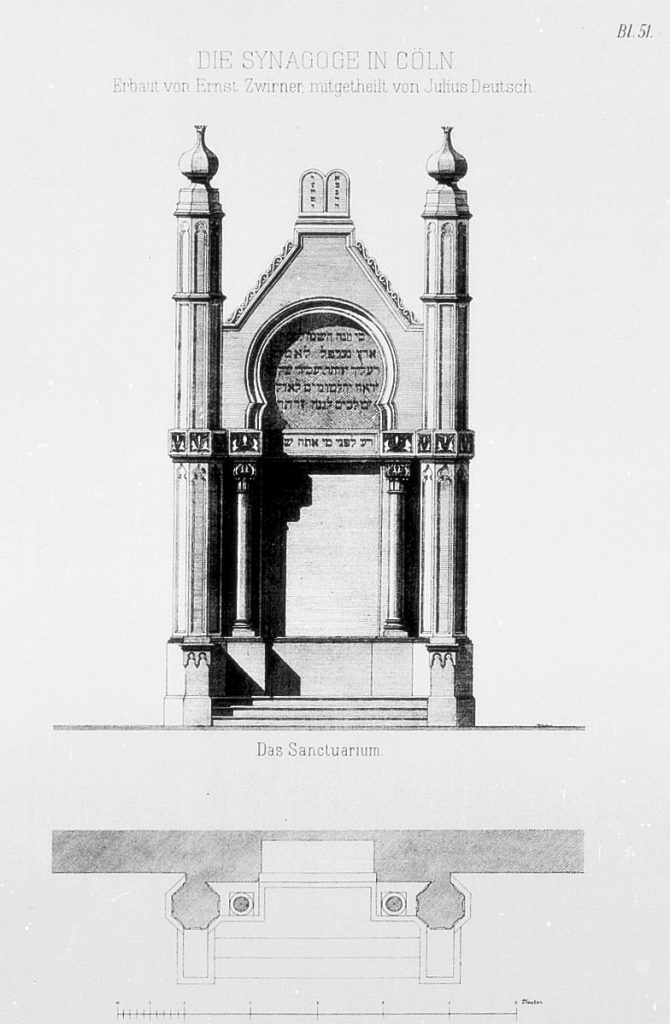

Due to the growth of the community and the disrepair of the prayer hall in the former Monastery of St. Clarissa, the Oppenheim family donated a new synagogue building at Glockengasse 7. The number of members of the community was now about of 1,000 adults. While in Medieval times the “quarter” had been built close to the synagogue in Cologne “Judengasse”, by now the Jews lived in a decentralized area among the rest of the population. Many lived in the new periphery quarters near the city walls.

The project was won by Ernst Friedrich Zwirner, leading architect of the Cathedral of Cologne, who designed a building in Moorish style. The new synagogue was inaugurated after four years of construction in August 1861. The inner and outside design was to remind the bloom of Jewish culture during 11th-century Moorish Spain. The new synagogue had a façade of light sandstone with red horizontal stripes as well as oriental minaret and a cupola covered with copper plates. The ornaments in the inside were inspired by the Alhambra of Granada.

The new synagogue, which was valued positively by Cologne people, had seats for 226 men and 140 women. While set on fire in November 1938, the rolls of the Torah of 1902 could be saved, thanks to the Cologne priest Gustav Meinertz. After the war they were placed in a glass cabinet in Roonstrasse Synagogue. After a restoration, carried out in Jerusalem in 2007, they are now used again in the liturgies in Roonstrasse Synagogue, rebuilt after the war.

Built between 1895 and 1899, the Roonstrasse Synagogue was also destroyed during the Cristal night. It was rebuilt in 1959 and hosts today a community center, a kosher restaurant and a permanent exhibition about Cologne’s Jewish past.

The modern times

The head office of the Zionist Organization for Germany was based in Richmodstraße near Neumarkt square, Cologne, and was founded by lawyer Max Bodenheimer together with merchant David Wolffsohn. Bodeheimer was president until 1910 and worked for Zionism with Theodor Herzl. The “Kölner Thesen” developed under Bodenheimer for Zionism were — with few adjustments — adopted as the “Basel Program” by the first Zionist Congress.

About 40% of the Jews of Cologne had emigrated by 1939. In May 1941, The Gestapo started to concentrate all Jewish from Cologne in so-called Jewish houses. From there they were transferred to the barracks in Fort V in Müngersdorf. On 21 October 1941 the first transport left Cologne for Łódź, the last one was sent to Theresienstadt on 1 October 1944. Immediately before the transport the fair hall in Cologne-Deutz was used as a detention camp. The transports left from the underground part of the Köln Messe/Deutz Station. The deported people went to Łódź, Theresienstadt, Riga, Lublin and other ghettos and camps in the east which were only transit points: from here they went to extermination camps. When the U.S. troops liberated Cologne on 6 March 1945, between 30 and 40 Jewish men who had survived in hiding were found. More than 11,000 Jews from Cologne were murdered during the Holocaust.

On the site of the Archeological zone of Cologne, a Jewish Museum is under construction since 2010. It will be about 7000 m2 and will explore 2000 years of Jewish presence in Cologne.

A small synagogue was built in 1949. The Jewish community underwent a small renaissance, and as the number of worshippers increased, a synagogue was built ten years later on Roonstrasse, on the site where the large synagogue was burnt down during the Shoah. The project was supported by the German Chancellor at the time, Konrad Adenauer, himself a former mayor of Cologne who had been dismissed by the Nazis. Representatives of the political, religious and cultural authorities attended the inauguration.

In 2020, a city streetcar was decorated with texts and symbols announcing the 2021 celebrations marking 1700 years of German Jewish presence. With the words “Schalomschen Koln!” emblazoned on the vehicle.

In 2025, Cologne’s Jewish community numbered 5,000.