Following the resurgence of antisemitic acts in France in the year 2000 and its continuity, many Jews moved, leaving the working-class areas where such attacks became banal, preferring to rent much small apartments in expensive neighborhoods where they felt safer. Two geographic zones have thus welcomed many Jews in the last twenty years.

The East, around the 11th and 12th arrondissements of Paris and the nearby suburbs of Saint-Mandé and Vincennes. And the West, around the 16th and 17th arrondissements and the suburbs of Neuilly, Levallois and Boulogne. But the link to those latter arrondissements is more ancient. In the 19th century, a small part of Parisian Jews migrate to the chic neighborhoods of the western part of Paris. Mostly towards the Parc Monceau area in the 17th arrondissement and the Victor Hugo place in the 16th.

Nowadays, the 17th arrondissement counts 40 000 Jews among the 300 000 living in Paris and its suburbs. Synagogues, restaurants, butchers, delis, schools… The cultual and cultural Jewish life is profuse in this area.

Nevertheless, the arrondissement was first influenced by a more ancient history, notably concerning the impact of important families. Among them, the Pereire brothers. Born in the city of Bordeaux, Emile in 1800 and Isaac in 1806, the pursued their financial career in Paris. Following the saint-simonianist philosophy, they wish to enlarge the economical development beyond its simple sphere. That its flourishment would enable the embitterment of the social condition of all the Parisians. This motivated the launching of grand scale projects. With the help of the State, the Pereire participated in the Universal Exhibit of 1855 and more important the renewal of the Haussmann neighborhood. They also developed the Crédit immobilier, a real estate bank, as well as the Gas heating company. And what they are also well known for, rail and sea transport.

In the 17th arrondissement and the nearby 8th arrondissement, they divide into plots parts of the Parc Monceau. Emile Pereire builds himself a hotel at 10 rue Alfred de Vigny. The brothers invest in real estate projects avenue de Villiers, boulevard Malesherbes and avenue de Wagram. And not far from those streets, building the Saint-Lazare train station. Elected Members of Parliament in the 1860s, the Pereire brothers fervently fought for the gratuity of education. Today, a square and a boulevard carry their name in the 17th arrondissement.

The Nissim de Camondo Museum , located on rue Monceau, is another important place linked to Jewish heritage in this neighbordhood. Abraham and Nissim Camondo, ennobled Italian bankers, bought the piece of land on a part of which the Museum stands today. Isaac Camondo, Abraham’s son, an astute art collector, made one of the greatest donations in the Louvre’s history, also enabling living artists, among which the impressionists, to find a place on its walls.

In 1911, Moïse Camondo, Nissim’s son, has the rue Monceau hotel rebuilt with the help of the architect René Sergent. A building inspired by the Petit Trianon’s architecture. Respected art collector like his brother, Moïse bequeaths the hotel and the artworks he placed there to the nation’s l’Union centrale des arts décoratifs (UCAD) in 1924. On the sole condition that the museum carries the name of his son Nissim, who died fighting during World War I. It’s considered today one of the most beautiful museums of Paris. Among the many books and artworks, a few Jewish books and objects still decorate it.

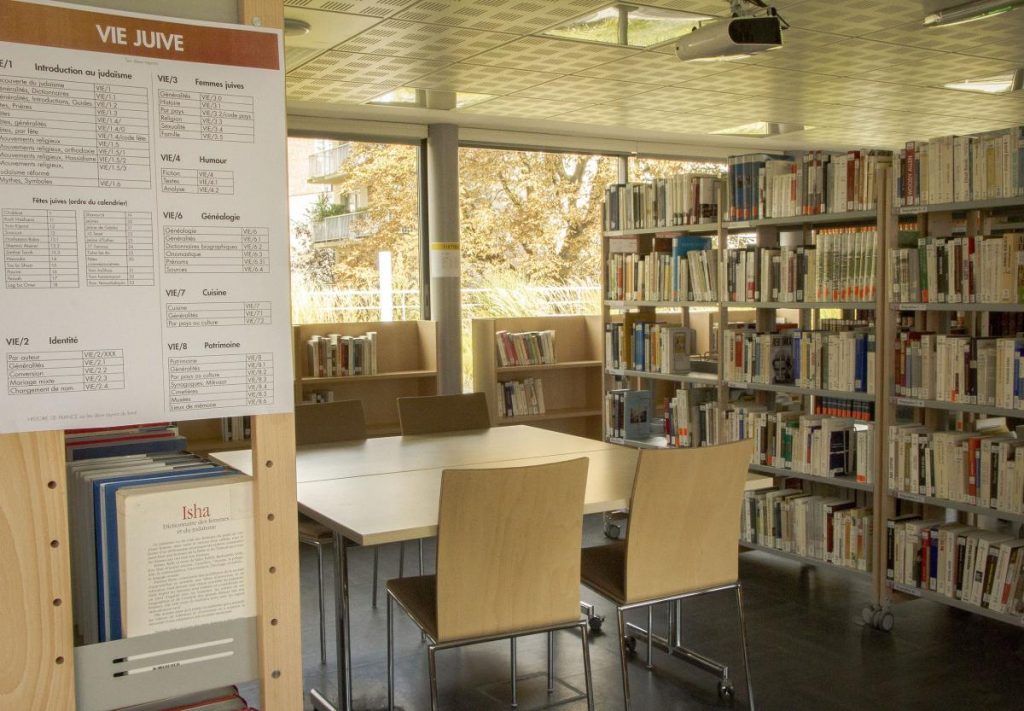

The 16th arrondissement has been welcoming different tendencies of Judaism for more than a century. Both orthodox and liberal. The area also hosts the biggest Jewish library in Europe.

A building mixing orthodox practice and modern architecture is located on rue Montevideo. Following a few resettlements of this community started in 1892 by the Société du culte traditionnel israélite, at avenue Malakoff, then rue Lalo, it was finally established rue Montevideo in 1934.

Built by the architects Julien Hirsch and Roger Kohn, this confined building of five floors welcomes the synagogue in its community center. The magen David isn’t a secondary decorative motif, as it is often the case in more ancient synagogues.

Here, it appears in different manners and colors, as one can witness on its concrete vault. The synagogue’s façade and its interiors are quite sober. Whether it be the bimah at its center or the metallic decorations.

On rue Copernic, close to the Victor Hugo square, stands the synagogue of the liberal Judaïsme En Mouvement (JEM). It was inaugurated in 1907 and headed by Rabbi Louis-Germain Lévy. In the beginning of the 1920s, the synagogue evolved architecturally.

This was caused by its extension and constructions in the courtyard. Mutations also occurred at the end of the 1960s. All those architectural changes explaining the different influences visible inside, between biblical inspiration and artistic movements of the 20th century.

The JEM Copernic synagogue has been the victim of two attacks. First during the Nazi Occupation and later on in 1980. The latter terrorist attack by a Palestinian group has caused the death of 4 persons and many wounded. Admittedly, the early 1980s antisemitic attacks and even more so the ones which started in 2000 have forced a more scrupulous securing of synagogues and Jewish schools, but they haven’t affected the worship, as is the case also regarding the liberal movement which attracts a growing number of Parisian Jews.

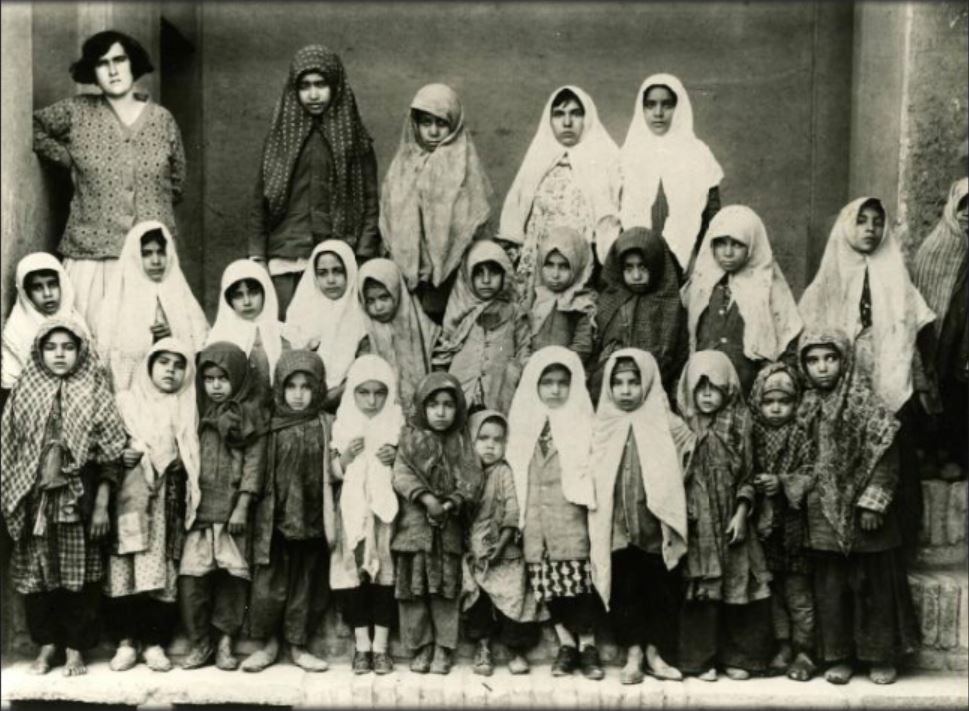

Hotspot of historical and cultural research on Jewish heritage, the Alliance Israélite Universelle’s library possesses the biggest European archives in those fields. Formerly at rue La Bruyère (in the 9th arrondissement), today it’s located rue Michel-Ange. The AIU, famous for its network of schools in Europe, Israel, au Morocco and North America, was created in 1860. With the aim of defending and sharing Jewish culture as well as promoting Human rights.

Nowadays, the AIU keeps sharing cultural and educational values in France and the French speaking world. College studies are also proposed by a cursus on « Biblical and Jewish Humanities » through its Institut Européen Emmanuel Levinas and the Collège des Etudes Juives – Beth Hamidrach.

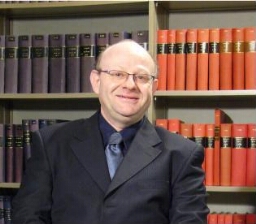

Interview with Jean-Claude Kuperminc, Director of AIU’s Library

Jguideeurope: Under what circumstances was the AIU’s Library created?

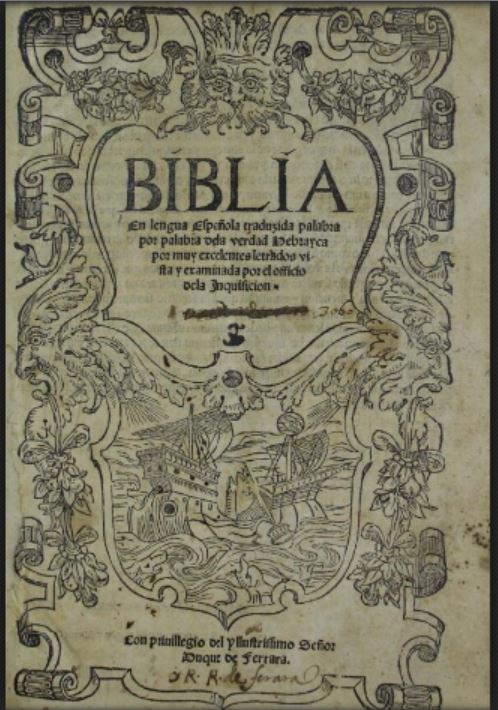

Jean-Claude Kuperminc: When the Alliance Israélite Universelle was created in 1860, it immediately required documentation to understand the fate of the Jews she wished to defend throughout the world. Thus, she establishes a resource center which would quickly become a patrimonial and savant library, under the influence of the AIU’s first leaders. Among which Salomon Munk, Isidore Loeb, the Great rabbis Israël Levi and Zadoc Kahn, who are also key figures in Jewish studies in France. The library receives books, theses, brochures, both from rabbis and the academic world. She also acquires important collections which are the core of its wealth, thanks to the outstanding donation of a benefactor, Benjamin Louis Mayer Rothschild (not related to the famous family) : the Salomon Munk Funds, exceptional manuscripts by Samuele David Luzzatto, the Zadoc Kahn Funds and the Bernard Lazare Funds. In 1939, while it just settled in functional offices at 45 rue La Bruyère, the library already holds more than 50 000 documents.

During the war, it is occupied and plundered by the Nazis working for Alfred Rosenberg. The books and documents are taken to Frankfurt where they’re part of a gigantic Jewish library. Fortunately, it was recuperated the American troops at the end of the war. Between 1945 and 1955, many books are given back to the AIU. Part of the archives, which were stolen by the Nazis and taken again by the Soviets in 1945, only emerged at the end of the 20th century and reintegrated our shelves in 2000. We have called it the Moscow Funds of the AIU archives.

Between 1937 and 1989, the library is resettled at the ground floor of the courtyard of rue La Bruyère. A new building is created there in 1989. Unfortunately, the AIU must leave its private mansion in 2016. Since then, the library welcomes its readers in one of its other historical locations, the former Ecole normale israélite orientale (ENIO) at 6 bis de la rue Michel-Ange, an address it left in 1937. Thus, we’ve come full circle. You can find on this link a movie presenting the library’s history in its former premises.

How many documents can be found at the library today and how do we have access to them?

It’s always hard to establish a detailed account. The library holds about 150 000 books, 3000 collections of newspapers, 1000 ancient manuscripts and 15 incunabulum works. She’s also the proud owner of 2 million items of archives of the AIU institution, essential for 19th and 20th century Jewish studies, particularly the Balkan, Mediterranean and Middle Eastern areas. Add to that 30 000 photos, movies, and sound recordings, then you’ll have an idea concerning the variety and importance of those collections. Since 2005, the library participates in the RACHEL network, which offers a catalogue of all the documents owned by several Parisian Jewish libraries. Since 2018, the AIU proposes its own digital library which gives a free access, free of charge, to more than 20 000 documents (books, newspapers, photos, movies, virtual exhibitions…) on the web.

Do you receive many requests for international research? Concerning especially cities, monuments or genealogy?

Much of our audience comes from abroad, including academics and PhD students. They use the archives of the AIU, but also our collections of old documents. We are partners of the Jewish Genealogy Circle, which actively works to locate names of people in our archives. The AIU was particularly effective in researching the life of its school personnel from 1860 to 1940 around the world. In our digital library, we have privileged documents on synagogues, with nearly 200 photographs and 80 books. You can find the testimony of a library reader at this link.

Among the documents received recently concerning cultural heritage, which one particularly interested you?

Two initiatives caught my attention. These are exceptionally beautiful books of historical interest on two of the most important Parisian synagogues: the Buffault synagogue, dedicated to the Sephardic cult of Portuguese rite, and the Synagogue de la Victoire. In both cases, the faithful of these places of worship have done a remarkable job of historical research and presentation in order to highlight the history of these prestigious buildings which have been illuminating the Parisian Jewish landscape for 150 years.

La synagogue de la Victoire : 150 ans du judaïsme français. Paris : Editions du Porte-plume, 2017.

Elie Balmain et Claude Nataf, Buffault : documents fondateurs et contractuels du Temple hispano-portugais. Paris : Editions E. Balmain, 2018

Which Parisian place of European Jewish cultural heritage do you think deserves to be highlighted?

Professionally, I would say the site of rue Michel-Ange, which today houses the library, the Gustave Leven School and the ENIO synagogue. The building is modern (built in 1965, rehabilitated in 2011), but the place is steeped in history with the statue of Moses, imitating Michelangelo, which was already present when the ENIO prepared the young teachers of the AIU to their future profession in schools. This is also where the philosopher Emmanuel Levinas lived as director of the ENIO. On a personal level, I will opt for the Fleischman Foundation, in the heart of the Pletzl, 18 rue des Ecouffes. It was in this shtibel that my father celebrated his bar-mitzvah in 1935. It’s one of the few locations still representative of the places of worship of Jewish immigrants who arrived from Poland in the 1920s.