Liege is a city known, like Ghent, for its large university population, but also for its cathedral, its waffles, and its film makers, the Dardenne brothers. The Jewish presence in Liege seems to date back to the Middle Ages. Documents from the 11th century attest to a local religious conflict between a bishop and a Jewish doctor. The case of a priest healed by a Jewish doctor is mentioned in 1138. But in the following centuries, the main mentions of Jewish presence are linked to local conversions to Christianity.

It was not until the French presence in the 18th century that the Jewish population settled there permanently. Thus, 24 Jews were counted in 1811, then about twenty Jewish families at the end of that century, mainly from the Netherlands, Dutch Limburg, Germany and Alsace-Lorraine. The oldest grave in the Jewish cemetery dates from this period. The formal recognition of the Jewish community in Liege did not take place until 1876.

A new Synagogue of Liège , marking this recognition and demographic evolution, was designed in a mixture of styles by the architect Joseph Rémont and inaugurated in 1899. Located near the Palais des Congrès, it is now listed as a historical monument by the Walloon Region.

The Jewish population of Liège increased at the beginning of the 20th century following the arrival of migrants from Eastern Europe working in the very prosperous industrial area of the time. But also Belgian and French students attracted by the quality of its University and the pleasant life in Liège. In 1914 the community, comprising Dutch and Alsatian Jews, was swollen by Russian Jews who had been taking prisoners by the Germans. Some of them settled in Liège from 1917. The international reputation of the École des Mines drew Jews from eastern Europe between the two world wars.

On the eve of the Shoah, there were nearly 3,000 Jews in Liège. About a third were murdered. At the Liberation, there were only 1200 Jews left in the city. Monuments in the synagogue commemorate the victims of the Shoah and also pay tribute to the Resistance fighters.

This number declined over time, reaching 594 in 1959. The community grew to 1,500 in 1968, but declined again to 1,000 in the early 1980s. Since then, the synagogue has also been used as a cultural meeting place.

Due to the unhealthy and dilapidated condition of the buildings next to the Jewish Cultural home and a construction project, it has been temporarily closed since 2022.

Small communities also existed in the surrounding towns of Seraing and Spa. The first one because of the workers of the industrial basin who settled there at the beginning of the 20th century and the second one because of the bathing stays of this city known for its water.

Sources : Musée juif de Belgique, Consistoire, Encyclopaedia Judaica, Politique et Religion : le Consistoire Central de Belgique au XIXe siècle

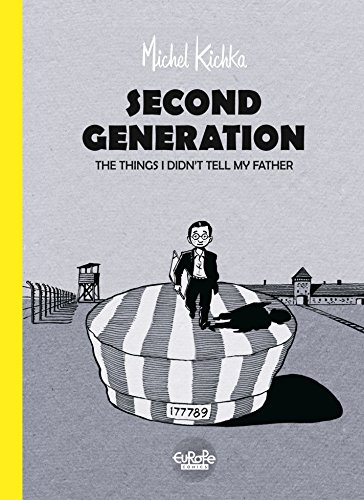

Michel Kichka devoted an album to his childhood in Liège and those memories difficult to share by his father, Henri Kichka, about the Holocaust. In his later years, Henri became an active participant in sharing his experience with high school students in Belgium.

Jguideeurope: You have shared your family’s history in the comic book Second generation. With its moments of happiness and its dark moments too, linked to the war. What motivated the wish of your family to settle in Seraing, in the outskirts of Liège?

Michel Kichka: My maternal grandfather settled there before the war. He opened a clothing store, convinced that there were some good opportunities in the economic heart of the region of Wallonia. His family was able to find a haven in Switzerland when Belgium was occupied. After the war, he came back to Seraing, after a detour via Brussels. My father and my mother managed a clothing store in Seraing, from 1952 or 53 until 1986.

What were the important places which, for your parents, then for you, evoked Jewish culture in the city of Liège and its region?

The Jewish Home of Liège (today we would use the term “Community Center”) where the community would meet for celebrations, was an important place. The synagogue of Liège also, actually there was only one. There, we would celebrate holidays, weddings and mixed bar and bat mitsvahs. The youth would regularly meet at the Ken (room) of the Hashomer Hatzaïr, located on the floors of the Jewish Cultural home.

The community was very homogenous, a big majority of Ashkenazim. Most of the fashion stores, selling men and women’s clothes, were kept by Jewish families in the heart of the city which, during my younger days, carried well its name: the “fiery city”!

What is left today of this heritage?

One of my childhood friends, Thierry Rozenblum, published a book about that subject entitled Une cité si ardente : les Juifs de Liège sous l’Occupation (published by Luc Pire, 2010). He’s working now on a second book. Over time, the majority of the families resettled in Brussels.

Michel Kichka, Second generation: the things I didn’t tell my father. Published by Europe Comics, 2016.