Unlike the majority of other cities in the region, the Jewish presence is attested in Orléans from the 6th century.

In 585, the Orléans Jews participated in the welcoming ceremony in homage to King Gontran. It seems that they asked him for the possibility of building a new synagogue following the destruction of the previous one. The Jewish community of Orleans was quite large in number in the Middle Ages.

Orléans became in the 12th century an important center of Jewish studies with personalities such as Isaac ben Menahem, Abraham ben Joseph, Eleazar ben Meir, Yaakov of Orleans and especially Joseph ben Isaac Bekhor-Shor.

The Jews were expelled from Orléans in 1182 and the synagogue turned into a chapel. They were able to relocate there, but under many conditions and impositions. There was in the following century a district of the Jewry and two synagogues in the city. But at the end of the 14th this relocation ended with the expulsion of the Jews from France.

Following the wind of emancipation from the French Revolution, a small community was reconstituted in Orléans in the 19th century with around 40 members having a synagogue.

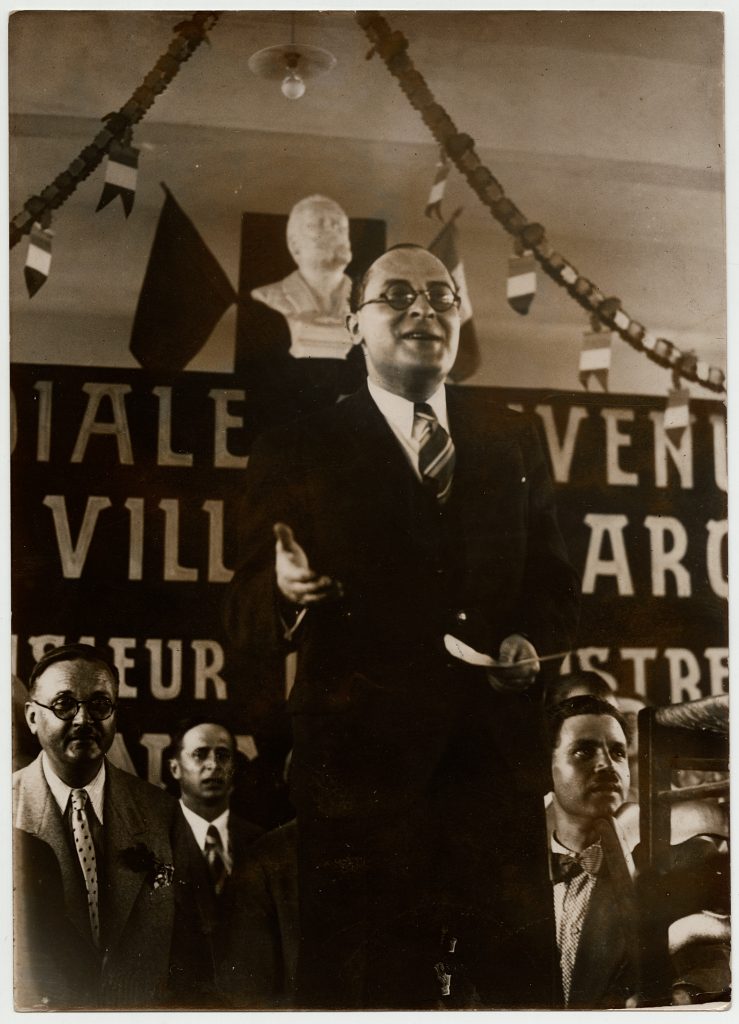

On a plaque commemorating the soldiers who died for France during the First World War is the name of Léon Zay. Director of the regional newspaper “Le Progrès” du Loiret, he was also the father of Jean Zay. The latter was born and raised in Orléans. Member of Parliament for Loiret, he became Minister of Education and Fine Arts in the Popular Front government from 1936 to 1939. He was behind many school reforms and the Cannes Film Festival. He left the government in 1939 to join the army and go to the front. He was arrested by Vichy troops and imprisoned in 1940. He was assassinated by militiamen in 1944.

The Nation paid a tribute to Jean Zay after the war. When he entered the Panthéon in 2015 (with the other Resistance fighters Germaine Tillion, Geneviève de Gaulle-Anthonioz, Pierre Brossolette), the city organized a series of events to mark the transfer of the coffin. A high school in Orléans bears his name. A strong tribute to Professor Samuel Paty took place there following his assassination in 2020.

In May 1969, Orléans Jews, who numbered around 500 people, fell victim to a conspiratorial rumor, creating a climate of tension in the city. The efforts of local authorities, intellectuals and the press deconstructed this rumor.

In 2020, the city has 400 Orléans Jews and a synagogue since 1970, located in a former oratory provided by the city and the bishopric.

Interview of Olivier Loubes, historian, member of the STUDIUM research group (University of Toulouse) and author of the book Jean Zay. The Unknown of the Republic (Colin, 2012), an expanded reissue was published, under the title Jean Zay. The Republic in the Pantheon (Dunod: Ekho, 2021).

Jguideeurope: How did you become interested in the work of Jean Zay?

Olivier Loubes: By chance and out of necessity. Chance was my appointment as a high school professor in Orléans in 1989. Necessity was my research work for a DEA, then a Thesis, which focused on the relationship between school and nation in the first half of the 20th century.

One day in the Les Temps Modernes bookstore in Orléans I was leafing through Jean Zay’s remarkable book Souvenirs et solitude which had just been reissued and the bookseller asked me what I thought of it. I share with her my admiration for this book and its author. With that, she confesses to me that it is about her father. This meeting with Catherine Martin-Zay changed my life as a historian. Catherine and her sister Hélène Mouchard-Zay, gave me access to Jean Zay’s personal archives, before they were given to the National Archives in 2010. Since then, I have written two books on Jean Zay, one on the creation of the Cannes Film Festival under his leadership, as well as some twenty articles to better publicize his work and his time.

What were the great moments of his life that linked him to Orléans?

As he said himself, Jean Zay knew every stone in Orleans. He was born there, spent his childhood there, studied from elementary school to high school. He worked there, in his father’s diary, then as a lawyer. His political life began as a deputy for Orleans in 1932. All his life (except his law studies in Paris) until his arrest in 1940 was linked to this city.

The republican commitments of Jean Zay motivated you in particular in the writing of this book. Are these beliefs inherited from his family?

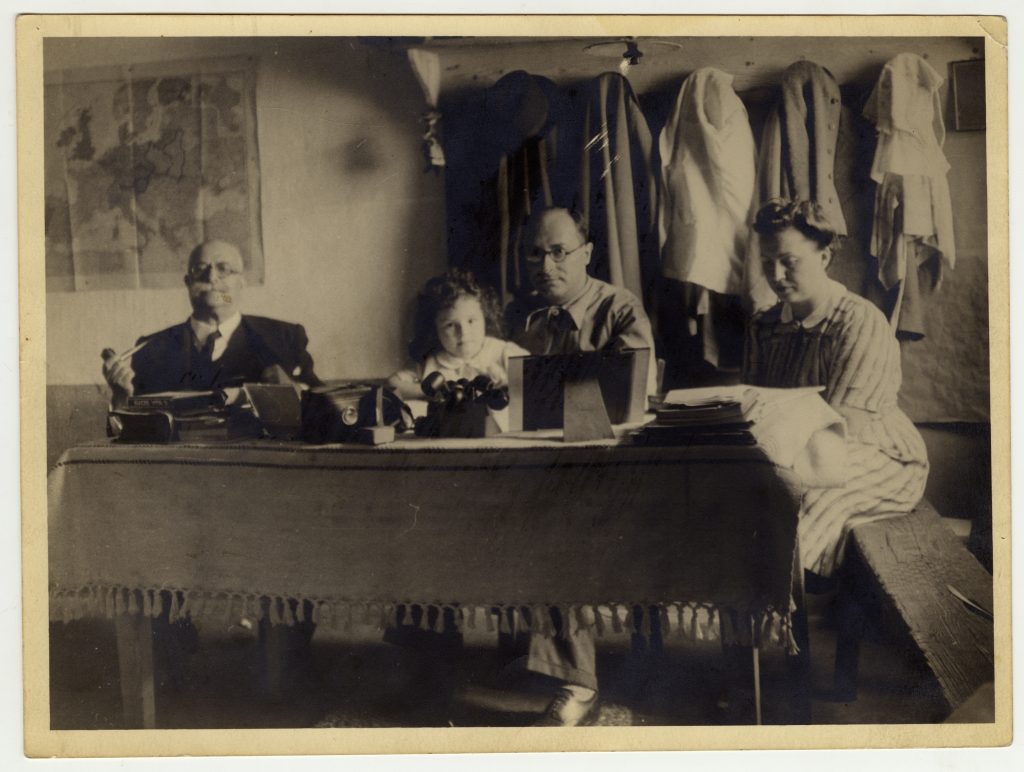

Jean Zay was born into a family of people “mad about the Republic” as Pierre Birnbaum calls them. With a Jewish father and a Protestant mother, these religious minorities who fought fiercely for this Republic which granted them equal rights. The family of his mother, Alice Chartrain, defended the cause of Captain Dreyfus. Originally from Alsace, his paternal family opted for French nationality in 1870, already showing a strong attachment. Léon Zay is a radical-socialist republican close to the Socialists, an employee of the Dreyfus newspaper Le Progrès du Loiret, of which he will become the Editor-in-Chief. Jean Zay grew up in this highly politicized family within the Republican left and got involved early, helping to found the “Republican Secular Youth” in Orleans. An approach anticipating the Popular Front, by bringing together young people from different left-wing parties. The bond with his parents remains very strong. When Jean Zay is imprisoned, his father (his mother was then deceased), his wife and his two children stayed in a hotel next to the prison to stay near him.

His Republican commitments are sometimes difficult to understand nowadays and not highlighted enough, motivating the writing of this book which was published in 2012 and is now available in pocket edition with additions, in particular on the pantheonization and the attacks that his person and his memory are still suffering. So many personalities claim his heritage, although sometimes very far from his vision, it was therefore interesting to present his commitment to the Republic. A parliamentary-type Republic that he imagined as a social democracy guaranteeing the right to education, housing, health, retirement …

How are these commitments important in our contemporary debates?

First, because these values of parliamentary republic and social democracy can inspire in depth many contemporary reflections on change in the Fifth Republic. It should be added that it is important to note that Jean Zay’s engagement also took place at a particular time. The anti-fascist dimension of his fight is not negligible, both in France and abroad. Jean Zay’s creation of the Cannes Film Festival is a direct response to Mussolini and Goebbels’ stranglehold on the Venice Film Festival. He is at the origin of cultural diplomacy, believing that liberal democracies must show their strength in this way.

Two fights led by Jean Zay are particularly echoed today. First, that the education be of the best possible quality and shared by all. Then, that the democratization of culture allows a strong political democracy. Combining action with rhetoric, he fought for better budgets and better use of education and culture.

Are his school reforms at the center of his fight?

Not when he began his political career in 1932, for he was then a generalist in politics. All predicted him a meteoric rise to the highest steps, being appointed minister at 31 years old. Nevertheless, in his concern for building social democracy, these fights for the school are at the heart of his project, since he was appointed Minister of National Education and Fine Arts in 1936. Si Jules Ferry wanted to make school accessible to all in order to train citizens, Jean Zay adds to it the desire that pupils and students from different social backgrounds continue their studies as far as possible so that they guarantee the functioning of democracy social.