An important city in the Champagne region, Troyes’ old town is shaped like a Champagne cork. With its renowned gastronomy accompanying its beverages, its many buildings protected as historic monuments, its Gothic cathedral and its churches and museums overlooking the Seine. Troyes is also famous in modern times for its textile industry, which flourished in the 19th century, particularly in the hosiery sector. Among the major brands created in Troyes are Lacoste, Petit Bateau and Dim.

The Jewish presence in Troyes probably dates back to the 10th century, at least according to documented archives. A few hundred people were present the next century. throughout the next centuries, the town has remained one of the most important centres of Jewish study of all time, thanks in particular to the immense Rachi de Troyes (his name being written RACHI in French and RASHI in English, we’ll use the original French form in this text), whose memory is honoured by the town and shared by the two places that face each other on the two banks of the rue Bunneval, the Institut universitaire et culturel européen Rachi (Rachi European University and Cultural Institute) and the Maison Rachi (Rachi House), linking the past and the future.

Rachi of Troyes

When you open the five books of the Torah, the Talmud or many other religious works, a word, or rather a name, accompanies your approach to these texts: Rachi. While various sources of commentaries on texts that have been shared for thousands of years can shed light on a particular point, situation or character, Rachi is unanimously recognised as the supreme reference. His ability to provide a link between the biblical texts and all the commentaries he has selected, comparing the most relevant approaches to the most complex questions. He makes reading easier by identifying the literal meaning, the pshat.

A national pride, Rabbi Shlomo Itshaqi, better known as Rachi, was born in the French town of Troyes in 1040. He received excellent rabbinical training from the rabbis Jacob b. Yakar, Isaac b. Judah in Mainz and Isaac b. Eleazar Ha-Levi in Worms, he resettled in Troyes and opened his own study centre. Between eastern France and western Germany stood an economically and intellectually prosperous region, encouraging exchanges on both levels.

As his pupils did not pay for their lessons at the time, the teachers were obliged to support themselves. Thus, since Rachi’s texts include numerous references to working in the vineyard, suppositions began to be put forward about his activity as a winemaker.

Rachi represents the junction of traditional excellence and modernism. As a leading intellectual figure, but also in his involvement in the community, he gave pride of place to the French language in his interpretations. Rabbi Claude Sultan, who directed the Rachi Institute, claimed that French linguists studied his biblical commentaries to discover French words from the Middle Ages. Rachi’s commentaries were not intended for the international audience that has been reading them since the development of printing a few centuries later. At the time, they were mainly clarifications intended for the communities of Champagne, where the langue d’oïl was spoken. When people didn’t understand a word, Rachi would write it down in the Champenese language, adding it to his text alongside the Hebrew terms. This was known as the laazim. Hence the great interest shown by linguists and philologists in these texts.

Christian religious texts, such as those of Nicolas de Lyre, also refer to them. Exchanges between Jewish and Christian thinkers were regular and warm. In Rachi’s time, but also in that of his descendants. His descendants, starting with his three daughters, Miriam, Yokhebed and Rachel, who carried on his teaching. Then, with the creation of the school of Tossafists. Among them were Rabbis Rashbam, Ribam and Rabenou Tam. This school spread throughout the region to Ramerupt, Dampierre and Sens.

All of Rachi’s writings were preserved and later copied. At the beginning of the 16th century, the Jewish community of Venice requested a printing of the Talmud. The publisher Daniel Bromberg obtained permission from the Pope. This was a revolutionary edition, with the text arranged in columns. The basic text is in the middle. Next to it, on the side facing the binding, is the text of Rachi. And towards the outside, the commentaries of the tossaphists. It is important to note that Rachi’s special characters were invented when his texts were published posthumously; he did not use them himself.

Jewish life in Troyes

In the Middle Ages, the Saint-Frobert district around Hennequin street was known as ‘la Juiverie’ or ‘la Broce-aux-Juifs’. Broce means “small dense forest”. It was located between the Quai des Comtes de Champagne and the Boucherat street. It was not a ghetto, Jewish and Christian populations living there in harmony. The old Jewish cemetery was located between the current Médiathèque Jacques Chirac and the Théâtre de Champagne. The Champagne fairs helped to expand the city of Troyes.

From then on, Jewish life in Troyes saw economic prosperity but also persecution, both material and physical, particularly in the 13th century under the reign of Louis IX. The following century saw expulsions under Philip the Fair and Charles VI and the timid return of Jews to the town. As the Jewish cemetery was destroyed to enlarge the town, Rachi’s tomb has disappeared. Not linked with the Jewish presence, a statue of Moses can be found on the corner of the aptly named Hôtel du Moïse, built in 1553 after Troyes burned down in 1524.

The Médiathèque Jacques Chirac (Jacques Chirac Media Library) owns extensive heritage collections, mainly from the 16th and 17th centuries, including those of the Clairvaux Abbey library. It was not until the 19th century that the Jewish community settled permanently in Troyes. On the eve of the Holocaust, some 200 Jews lived in Troyes.

Rebirth of a community

Isidore Frankforter was a businessman of Romanian origin who settled in Troyes. In New York, he met Walter Artzt, a Ukrainian Jew. Haas had designed a special fabric that was stretchable. Frankforter set up the company FRA-FOR and received a monopoly from Haas on the use of his fabric in France. Thus was born the Babygro brand. A success enabling Frankforter to become a pillar in the reconstruction of Jewish life in Troyes.

In the aftermath of the Shoah, there was no longer a Jewish place of worship in Troyes, as it had been severely damaged during the war. In the 1960s, Isidore Frankforter and Rabbi Abba Samoun bought the small house in which today’s Maison Rachi is located at 5 rue Brunneval and then extended it to 7 and 9, buildings they had acquired in 1966.

Frankforter and Samoun wanted to repopulate this community, which had been cruelly affected by the Shoah, and met refugees from North Africa who had landed in Marseille. As en encouragement, they justified “it’s true that Troyes doesn’t have the sun, the mountains or the sea… but there is work”, because the textile industry was flourishing at the time. By the 1960s, there were 350 families in the Jewish community.

Memorial

When the Troyes City Council wanted to pay tribute to Rachi, it could not do so in the old quarter, because of all the building work that had been carried out since the Jews had been expelled there in the Middle Ages. The choice fell on the nearest possible location: the esplanade on which the famous memorial stands opposite the Théâtre de Champagne, located on the place of the destroyed medieval Jewish cemetary.

To mark the 950th anniversary of Rachi’s birth in 1990, the Rachi Memorial , designed by the sculptor Raymond Moretti, was inaugurated in front of an emotional audience. Among them were Robert Galley, the former mayor of Troyes, and Elie Wiesel. The latter recalled the importance of Rachi: ‘His commentary became my companion. Rachi was there, guiding me, telling me that everything is simple despite appearances. I began to love him so much that I couldn’t do without him because, from then on, I found that he was different, radiating friendship.’

Made up of a metal sphere almost 3 metres high, the artist drew his inspiration from the Kabbalah and the acronym for Rachi in Hebrew can be seen on the sphere, which measures 2.20 metres in diameter. It is placed on a hexagonal bowl that features David’s shield and the Hexagon representing France.

Today, the cultural and religious activities of Troyan Judaism are centralised in two places. The Rachi House and the Rachi European University and Cultural Institute provide a complementary approach to appreciating the work of the great master.

Rachi European University and Cultural Institute

Built in 1990, in the same spirit of celebration of the 950th anniversary of Rachi’s birth as the Memorial, the Rachi European University and Cultural Institute today occupies an important place in Jewish study but also in intercultural sharing. Through the study of the Hebrew language, other Semitic languages and comparative civilisations and thought. Troyes’ town hall, the media library and the University of Reims are actively involved in sharing Rachi’s work and influence on biblical, linguistic and cultural studies. Numerous artistic events are also organised there.

Interview with Gérard Rabinovitch, Vice-President of the Rachi European University and Cultural Institute (IUCR).

Jguideeurope: When and how did the idea of creating the Institute come about?

Gérard Rabinovitch: It is essential to remember that the Rachi European University and Cultural Institute was founded over thirty years ago on the initiative of René Samuel Sirat and Robert Galley. Each of them, and together, put the stamp of their personal commitments on the spirit that drives the Institute. They were two exceptional personalities.

René Samuel SIrat was a university professor, responsible for Hebrew language teaching at the Inspectorate General of National Education. He was also a professor at INALCO for thirty years, where he headed the Hebraic and Jewish studies section. In addition to his academic activities, he was Chief Rabbi of France from 1981 to 1988. And at the intersection of his two titles, he founded the UNESCO Chair in ‘Mutual Knowledge of the Religions of the Book and Teaching for Peace’. The French nation elevated him to the prestigious title of Grand Officer of the National Order of Merit.

As for Robert Galley, he was what we call, with consideration and admiration in France, an ‘early’ Resistance fighter, promoted to the title of ‘Companion of the Liberation’. He was an engineer who graduated from the École Centrale de Paris, but above all he was a politician who served as a minister several times between 1968 and 1981, was a member of parliament for Aube and mayor of Troyes. Of Christian tradition, he was very involved in the Judeo-Christian friendship movement, for which he was awarded the prize in 1995. Robert Galley was hailed as a great figure in the service of the country, being elevated to the title of Grand Officer of the Legion of Honour.

The spirit of the Resistance, high academic standards, a biblical humanism, a hermeneutic of the fundamental texts, and the dialogue of cultures, inherited from them, inspire the activity of the Rachi Institute.

From the inspired and initial impetus of its two founders and their successors – including Nelly Hanson, who ensured the perpetuation of its spirit – the Rachi European University and Cultural Institute defines itself as an establishment devoted to the humanities (biblical and Jewish humanities, and European humanities in their intersections, seeding or tensions) in the academic sense of higher and secular education. It offers courses, seminars, research groups, conferences and symposia. It also organises exhibitions, evenings and artistic events focusing on music, literature, poetry and film.

Precisely, with all these teaching tools, the Rachi Institute aims to provide tools and benchmarks for thought and reflection on what we might call monotheistic cultures. The transmission of Jewish thought and culture in all its diversity is one of its key areas of focus, as is the establishment of links and dialogue with other monotheistic cultures on the major ethical and epistemological issues facing our contemporary societies. It seems obvious to me that the magisterial use of Rachi’s name has a strong influence on this.

What does the name of Rachi and the wealth of his teachings inspire in you?

The name Rachi – an acronym for Rabbi Shlomo Ben Izhak, also known as ‘HaTzarfati’ (The Frenchman) – his person, as he has been described as ‘simple’ and ‘modest’; his existence, as the founder of a School that had students from all over the continent of his time; his work, so important that it has been added – under the name of the Rachi Commentary – to the Talmudic corpus, even though it has been considered closed for centuries; all together, it stamps and marks out many of the paths of Jewish and non-Jewish erudite Europe, which was inspired by it.

For the record, the Rachi Commentary was the first book printed in Hebrew in 1475 in Reggio, Italy. At one and the same time rabbi, exegete, talmudist, poet, legal scholar and decision-maker, we can say that he represents – through his person, his life and his work – a kind of ideal type embodying the three recurring intellectual fields of Jewish scholarship: exegetical study, law and poetry. Let us add to this portrait that he embodies the intertwining of the positions of pupil to his masters (those of Mainz, then Worms) and master in turn to pupils (in Troyes) such as Jewish sociality venerates, in a continuous chain.

But perhaps even more than that, for a teaching establishment such as the Rachi Institute, he personifies – in my opinion – what can be the trait of an educator’s subjectivity, at the core of his existence and in all the horizons of a life justified by his actions. In the simplest terms, we could already highlight the fact – so rare in his time – that he took care to teach his three daughters (Miriam, Rachel, Yokhebed). They later married three of his best pupils from the Talmudic School he had founded.

His educational trait is still actively present in the initial motif of his Commentary. The fruitful impetus of this gigantic work is to be found in the desire to bring together all the answers that can be given to a five-year-old about the meaning of the texts, while remaining as concise as possible. Along the way, he established a cognitive system of deduction and conclusion, based on relating the dissimilarities between one example and another.

This trait is no less evident in his Responsa, which enabled Jewish populations confronted with unprecedented life situations to deal with them, by inventing recipes, remedies and responses that could accommodate the unprecedented without departing from the ethical-practical Law.

Finally, we can even see this in his use of the French vocabulary of his time. Borrowed precisely to explain ‘in the text’ a difficult term from the Pentateuch and the Talmud. The words he borrowed – for didactic purposes – from the vernacular French of his time (known as laazim in Hebrew) are so numerous and rich (1,500 to accompany the biblical text, 3,500 to accompany the Talmudic text) that the Rachi Commentary constitutes – according to Claude Hagège and Arsène Darmasteter – the most precious document we have on the state of French as it was spoken in the second half of the tenth century.

Here are a few examples of laazim: chêne, portail, bordel, sommeiller, châtaigner, cannelle, bandeau, chat-huant, pape, fourgon, coudrier, vire, aigrin, contrefait, vautour, assiégeur, aise, huisserie, houblon, fusil, orme… And also the famous tcholent meal, from Chaud lent! With Rachi, we have not only a magisterial figure of Jewish erudition, but also a sublime figure of the European ideal of culture through education.

And if I may say so, I would add that some of Heinrich Heine’s and Abraham Heschel’s formulas on presence, existence and the Jewish condition in the world and its contribution fit him perfectly. If I were to combine them and apply to Rachi, I would sum them up as follows: Rachi was not a builder of Pyramids, but a Builder of Time. You can see that as an educator in his essential being, Rachi is the most honourable name as a roadmap for the Institute, its management and its teams in Troyes.

What contemporary projects is the Institute involved in?

Amongst all its work, and in line with its educational and cultural missions, the Rachi Institute is a partner in the GIP Rachi project, a ‘Rachi-Troyes & Grand Est’ public interest group created in 2023. The aim of this GIP Rachi is to promote the European legacy of Rachi de Troyes to the status of ‘European Heritage’. This should be a matter of course for those who appreciate all that it symbolises.

Otherwise, under the big top of Hesiod’s poem ‘Works and Days’, the Rachi Institute takes part in teaching projects with educational partners such as the University of Reims Champagne Ardennes, the Troyes University of Technology, the École supérieure de Design, Y Schools, the Lycée Marie de Champagne; and in Paris, with the AIU’s European Institute Emmanuel Levinas.

It takes part in cultural activities with the Médiathèque Jacques Chirac, the Friends of the Médiathèque de Troyes Champagne Ardennes, the Maison du Boulanger, the Espace culturel Didier Bienaimé, Aube Musique ancienne, the Passeurs de texte, and the Protection judiciaire de la jeunesse.

It also maintains links within academic Europe in the form of teaching and colloquia, and with several Cultural Centres of foreign representations in France, particularly in Eastern Europe. For example, the Polish and Lithuanian Cultural Centres. And we hope to develop them further.

Rachi House

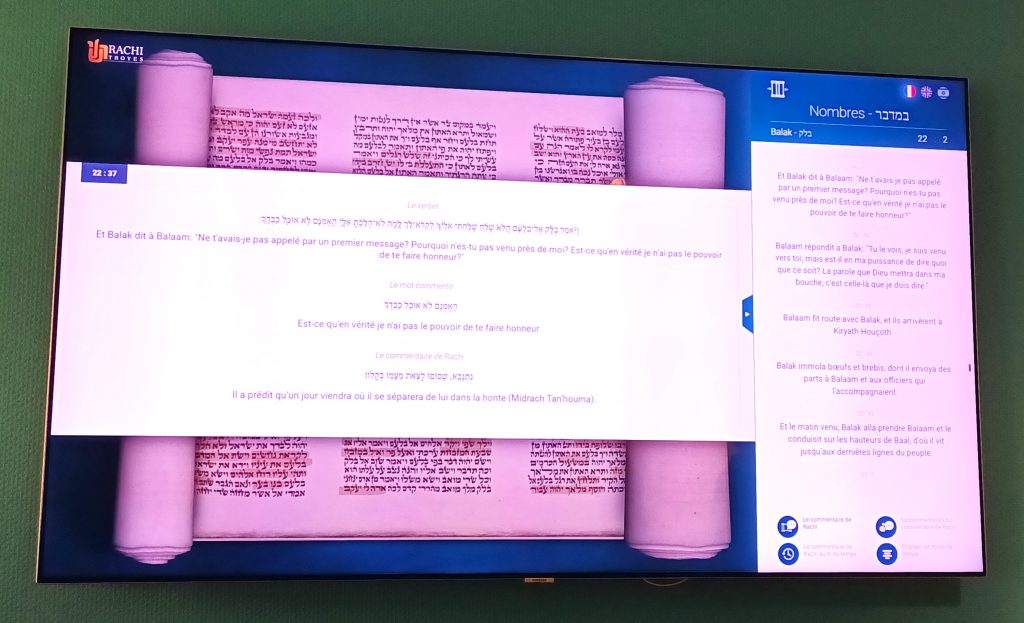

In 2017, the Rachi House was created inside the synagogal space dating from the 1960s. Renovations have been carried out on the interior in recent years, with the installation of a beautiful glass roof combining the different eras. The building has a rich and varied permanent exhibition. It also offers the possibility of consulting all the works containing texts by Rachi in its library, as well as through digital research.

This place is called Maison Rachi (Rachi House) and not Maison de Rachi (Rachi’s House), because the great master probably lived in the old Jewish quarter. What surprises visitors arriving in Troyes is the absence of any material traces. Museums were not fashionable in Rachi’s time, and the lack of financial resources and the difficult situation of the Jews in France at the end of the Middle Ages meant that much was lost over time. It was therefore the main aim of the Maison Rachi to present the work and life of the world’s greatest exegete and most published French author to a wider public.

At the end of the 20th century, major maintenance work was required on the building. The Edmond J. Safra-Geneva Foundation financed the start of this work. Other institutions, as well as private individuals, subsequently contributed to the funding.

At the entrance, you are greeted by Flavie Serrière Vincent Petit’s magnificent stained-glass windows depicting Rachi’s family tree. They were created in 2016, with the help of Jewish historian Gérard Nahon and exhibition curator Delphine Yagüe. The tree is rooted in the names of his three daughters, Miriam, Yokhebed and Rachel. This is followed by the many branches and birds placed on it, allowing his thoughts to fly away to the heavens and return to populate the commentaries on religious texts in the four corners of the world for so many generations…

The parashah of Balak was chosen to accompany the museography of the building. It tells the story of King Balak sending Bilam to curse the people of Israel. An angel appears and encourages him to do the opposite. When he arrives in front of the camp in the time of Jacob, he recites the blessing: ‘How beautiful are your tents, Jacob, and your dwellings, Israel! This text, selected by the House of Rachi, was sent to the architect to inspire his work.

The special feature of the synagogue at Maison Rachi is that it is located in an inner courtyard, under a glass roof. The metal mesh next to the glass roof symbolises Jacob’s tents. An amusing anecdote: as the work was taking longer than expected, the inauguration date was postponed and, as chance would have it, it took place during the week of Balak’s parasha.

All the texts by Rachi that have been found are on display in the magnificent library. 1800 volumes in a wide variety of languages, including French, German, English, Spanish and Italian.

The path we have travelled during the visit allowed us to appreciate a very special museography for each room, with ancient objects and texts, as well as video and research screens. The aim is to tell the story of Rachi’s life and times, as well as the foundations of Judaism. To enable the general public to understand and contextualise this history. We were astonished by an animated film in which viewers follow period characters, including Rachi, as they give a lesson. With the voices of Marc-Alain Ouaknine, Rébecca Eppe and Zacharie Yagüe.

On the 2nd floor, a room is devoted to the post-war activities of the Jewish community in Troyes, in particular the events organised by the youth movement Eclaireurs Israélites. A number of photos are displayed on these walls, including those of one of Troyes’ most famous contemporary figures, the comedian Raphaël Mezrahi. Mezrahi often refers to his hometown in his work.

The next room features a digitised Bible text, providing quick access to each parasha. In French, English and Hebrew. This room also contains texts by Christian thinkers from the late Middle Ages who studied Rachi, including Nicolas de Lyre. He points to Rachi’s contributions to his understanding of the Bible. Luther used Rachi to perfect his translation of the Bible into the vernacular. The next room shows examples of laazim.

Jean-No, an artist from Lorraine, has created a work using metal letters with the characters of Rachi. With the name in stainless steel and the same hexagonal base, like the one at the Rachi memorial opposite the Champagne theatre. In the small inner courtyard, you can contemplate the famous work of the ‘Burning Bush’.

During the works, consideration was given to the possibility of installing a lift, in particular for people with reduced mobility, as is customary in all contemporary museums. However, as the Maison Rachi is located in a listed building, special authorisation was required. The agreement provided for the installation of an external lift, set up in the courtyard and providing access to the various floors. To conceal the lift in the courtyard, a work of art was created over it, measuring nine metres high and one and a half metres wide. The work was created by Flavie Serrière Vincent-Petit, whose family tree greeted us at the entrance to the Maison, and whose creations we follow along the way.

Interview with Jean-David Bensaïd, Head of Development Department at Maison Rachi.

Jguideeurope : What types of tour do you offer?

Jean-David Bensaïd: We currently offer two types of guided tour, lasting one or two hours. We are currently working on setting up self-guided tours. This route would integrate the synagogue, library and oratory in a new and innovative scenography that should be operational next spring.

What other activities are organised at Maison Rachi?

There are many events. For example, we have just welcomed Arlette Testyler, a survivor of the Vel d’Hiv massacre, whose testimony brought together 2,000 schoolchildren at the Théâtre de Champagne. In December 2024, we welcomed François Guillaume Lorrain for his book dedicated to the Righteous, which was one of the last three essays shortlisted for the Prix Renaudot 2024. The Maison Rachi can even be used privately for certain events, such as the reception for the annual seminar of the National Library of Israel next February.

Maison Rachi is also a publishing house. We regularly publish booklets, which, through a fairly detailed popularisation process, enable readers to discover a wide range of themes such as women’s rights and anti-Semitism. Incidentally, we have reworked our entire range to ensure greater consistency with the major New York publisher Prosper Assouline.

Finally, and I was going to say above all, Maison Rachi is a very dynamic synagogue. We are fortunate to have a rabbi, Mickael Amar, who is very active and who, in close collaboration with our two co-presidents and our vice-president of the religious association, regularly organises community activities for the holidays and beyond. The number of full Shabbaths is increasing, which means that we can welcome visitors who want to spend a special moment in the city of Rachi in excellent conditions.

Can you tell us about a visit that particularly moved the people working at the House of Rachi?

Philippe Bokobza, one of the two co-founders along with the President of Maison Rachi, René Pitoun, told me about a very touching visit from one of our visitors who, faced with the digital tables in front of which you can discover each parasha of the year, found the one for his bar mitzvah. He found himself plunged decades back in time and began to sing, with tears in his eyes.

These tables, unique in the world, provide direct access to the sacred text and are much appreciated by our visitors. Adults and children alike find themselves immersed in Rachi’s commentaries in French, English and Hebrew, and they are truly moved.

And to finish this presentation and wish you a pleasant visit, a few aphorisms from Rachi:

Any plan formulated in haste is foolish.

Be sure before you ask your Master about his reasons and sources.

Masters learn from the discussions of their pupils.

Anyone who studies the Laws and does not understand their meaning or cannot explain their contradictions is just a basket full of books.

Do not blame your neighbour in such a way as to shame him in public.

To obey out of love is better than to obey out of fear.

During the Middle Ages, the Aube Region in France hosts many Jewish communities including Villenauxe-la-Grande, Saint-Mards-en-Othe, Plancy-l’Abbaye, Ervy-le-Chätel, Lhuître, Mussy-sur-Seine, Ramerupt, Dampierre , Brienne-le-Chäteau, Bar-sur-Aube and especially Troyes.

The Jewish presence in the city of Troyes probably dates from the XIth century, a fact which can be verified from documented archives. Probably a few hundred people. But among whom the great scholar Rashi.

By opening the five books of the Torah, the Talmud or many other religious works, a word, rather a name accompanies the approach of these texts: Rashi. If comments from texts shared for millennia shed light on such a point, such a situation, such a character, Rashi is unanimous as a leading commentator.

By his capacity to make the link between the biblical texts and all the comments which he has selected, confronting the most relevant approaches to the most complicated questions. He facilitates its reading, by finding the literal meaning of reading, the Pshat.

National pride, Rabbi Shlomo Itshaqi, better known by the name of Rashi, was born in the French city of Troyes in 1040. Having benefited from an excellent rabbinical training with the rabbis Jacob b. Yakar, Isaac b. Judah in Mainz and Isaac b. Eleazar Ha-Levi in Worms, he resettles in Troyes and opens his institute. Between the East of France and the West of Germany a region was prospering economically and intellectually, encouraging the exchanges on the two plans.

Rashi also represents the junction of traditional and modern excellence. A primary reference in text comments but also in its investment in the City, he also highlights the French language in its comments. Rabbi Claude Sultan, who directed the Rashi Institute, said that French linguists were studying his biblical commentaries to find French words from the Middle Ages, Rashi not in fact hesitating to use the language of Molière and the regional language of Champagne to clarify a comment when there was no equivalent in Hebrew. Christian religious texts, like those of Nicolas de Lyre, also refer to him.

The exchanges between Jewish and Christian thinkers are moreover regular and warm. At the time of Rashi but also of his descendants.

Descendants who perpetuated his teaching by creating the school of the Tossafists. Among them are the rabbis Rashbam, Ribam and Rabenou Tam. This school shines in the region in Ramerupt, Dampierre and Sens.

Jewish life in Troyes gradually experienced economic prosperity but also persecution, both material and physical, particularly in the XIIIth century with the reign of Louis IX. The following century saw expulsions under Philippe le Bel and Charles VI and timid returns of Jews to the city.

The old Jewish quarter was located near the Saint-Frobert church and the Jewish cemetery at the entrance to the suburb of Preize. The cemetery having been destroyed to enlarge the city, the tomb of Rashi has disappeared. Near the rue de Preize, an esplanade in front of the Jacques Chirac Media Library was named in memory of Rashi. The Media library possesses vast heritage funds, mainly from the XVIth and XVIIth centuries, among them the ones held at the Clairvaux Abbey library.

In the Middle Ages, the Saint Frobert district, around rue Hennequin, was nicknamed “la Juiverie” or “Brosse aux juifs”. At the time of Rashi, many Jews lived in this neighborhood.

It was only in the XIXth century that the Jewish community settled permanently in Troyes. On the eve of the Holocaust, some 200 Jews lived in Troyes. Today, a few hundred Jews live in the department of Aube.

1990 marked the 950th anniversary of Rashi’s birth. Therefore, two major events during that year honored Rashi’s influence. The latter one was the presentation of the Rashi Memorial , created by the sculptor Raymond Moretti. It was inaugurated before an emotional audience. Among them, Robert Galley, the former mayor of Troyes and Elie Wiesel. The latter recalled the importance of Rashi: “His comment has become my companion. Rashi was there, guiding me, telling me that everything is simple despite appearances. I began to love him so much that I could not do without him because, from then on, I found him to be different, radiant with friendship. “

The memorial is located in front of the Champagne theater. Consisting of a metal sphere of almost 3 meters, the artist was inspired by the Cabbala and we see the acronym of Rashi in Hebrew.

Nowadays, two places centralize the cultural and religious activity. The Rashi Synagogue and the European University Institute Rashi, one opposite the other, are located in the old town of Troyes.

In 1960, the Rashi Synagogue was installed in the old town. Wood is much used in the architecture of building, in harmony with the antiquity of the district. Interior renovations have been carried out in recent years with the installation of a beautiful glass roof, combining eras. There is also a beautiful stained glass window inspired by Rashi’s family tree. The Rashi House, created there in 2017, offers a permanent exhibition about Rashi. The building also holds a library, movies and numerical tools presenting precious manuscripts.

In 1990, in the same spirit as the inauguration of the Memorial, and preceding it, the Rashi Institute opened its doors that year. Today, Since then, it has occupied an important place in Jewish studies but also in intercultural sharing. By studying the Hebrew language, other Semitic languages as well as compared thoughts and civilisations. And by asking the question of the cultural and scientific approach to religion. The Town Hall of Troyes, as well as the Media Library and the University of Reims actively participate in sharing Rashi’s work and influence, precisely on biblical, linguistic and cultural studies.