Trondheim’s synagogue is doubly unusual: it is the northernmost synagogue in Europe and the only one that has served as a train station, before the building became a synaogue in 1925!

Jews first settled in Trondheim in the 1880s. They quickly became very integrated, participation in all economical, social and cultural aspects of life. The Jewish community in Trondheim has never really recovered from the mass deportation of its members in March 1942. The city’s Jews were arrested by the Norwegian police and were detained at the Falstad camp, near Trondheim.

Today, the synagogue also welcomes the city’s Jewish Museum. The museum opened in 1997, celebrating the city”s 1000th anniversary. The latter proposes two permanent exhibitions. One devoted to the life of Jews in Trondheim and in the area. A second one focuses on the historical aspect of the Jewish community in Trondheim, especially during the Holocaust and the impact thereafter.

The museum also focuses on themes such as immigration, diversity, identity, integration, antisemitism before and now, and genocide together with the relationship between minority culture and the societal majority. Educational programs have been created by the museum and a large number of the museum’s visitors are pupils from primary school and high school as well as students.

A Holocaust Mémorial has been built at the city’s cemetery.

Interview with Tine Komissar, Manager of the Jewish Museum of Trondheim

Jguideeurope : Can you present us some of the objects shown at the museum?

Tine Komissar: Here are 4 objects I’m happy to present to you.

Prison suit. It was owned by Julius Paltiel of Trondheim (1924-2008). Most of the prison uniforms from the Nazi concentration camps during World War II were made in the sewing barracks at some of the larger concentration camps, including Dachau, Sachsenhausen and Ravensbruck. Despite the fact that the uniforms were made in different sizes, which were not marked on the suits, the suits were not distributed adapted to the size of the prisoners. The prisoners therefore had to adapt their own prison uniforms so that they fit better.

The marks on the suits consisted of a rectangular shaped patch, usually in cotton, with prisoner numbers in addition to a triangular-shaped patch with letters. The triangle referred to the different types of prisoners, and was color-coded; yellow triangle for Jewish prisoners, red for political prisoners, green for criminal prisoners, black for “antisocial” prisoners or Roms, pink for gay prisoners and purple for prisoners belonging to Jehovah’s Witnesses. The letters in the triangle referred to nationality.

This prison suit belonged to Julius Paltiel. In October 1942, he was deported by the Nazis from his home in Trondheim. He was detained at Falstad prison camp, before being sent on to Bredtveit prison in Oslo. In February 1943, he was sent with the ship D / S Gotenland to the concentration camp Auschwitz. Upon arrival, Julius was taken out to forced labor. He miraculously survived his stay in Auschwitz, and the death march of the Buchenwald concentration camp. In the weeks before the liberation in 1945, Julius went into hiding from the Nazis, who systematically picked out the Jewish prisoners in the camp. Everyone who was gathered was shot. The SS soldiers followed orders from Berlin that everyone should be exterminated.

In order not to be discovered, Julius tore off the yellow mark on the prisoner’s suit. He then took a non-Jewish mark from a dead prisoner and sewed it on his own suit to make it harder to detect that he was Jewish. This is why the suit has a red triangle, as shown in the picture. Buchenwald was liberated by American forces on April 11, 1945.

When Julius returned to Trondheim after the war, his family and many friends were gone. He resumed the family business, spending the rest of his life telling his story, including to thousands of young people around the country.

Wedding dress. It belonged to Malke Rachel Mahler (f. Leimann). She was born on April 2, 1896 in Śniadowo, Poland to parents Samuel and Lea Leimann. She came to Norway and Trondheim in 1916. Simon Mahler had already been in the country for three years. He was born on December 31, 1886 in Saldus, Latvia. He made a living as a transport trader and had traveled a lot both in Sweden and in Norway when the two met.

Malke and Simon married in 1916/1917. They settled in Tempe, having five children: Sara Bella (1918), Abraham Bernhard (1920), Salomon Hirsch (1922), Selik Elieser (1923) and Mina Scholamis (1927).

Malke, Simon, and the children Abraham, Selik, and Mina Mahler were deported and killed in Auschwitz during World War II.

Only Solomon and Sarah survived. Salomon managed to escape to Sweden. Sara was married to a non-Jewish man, and was not deported but imprisoned in several concentration camps in Norway during the war.

Cart, Production 1895 – 1905. The cart is probably from approximately 1900. Hennoch Klein came to Norway from Lithuania in the mid-1890s. He settled in Trondheim in 1901, after several years as a transport trader. Here, he started the business H. Klein in 1902, which operated in Trondheim until 1978. A continuation of the store, Kleins, is still run today by Henoch’s great-grandson, Robert.

Henoch Klein’s son, Josef, has said that every day he pulled the cart with him from his home in Øvre Møllenberg street to the family-run business, H. Klein, which in the 1910s was located by Bakke Bridge in Trondheim. The origin of the carriage is uncertain, possibly it was taken by the Klein family when they moved to Trondheim from Lithuania in the 1890s.

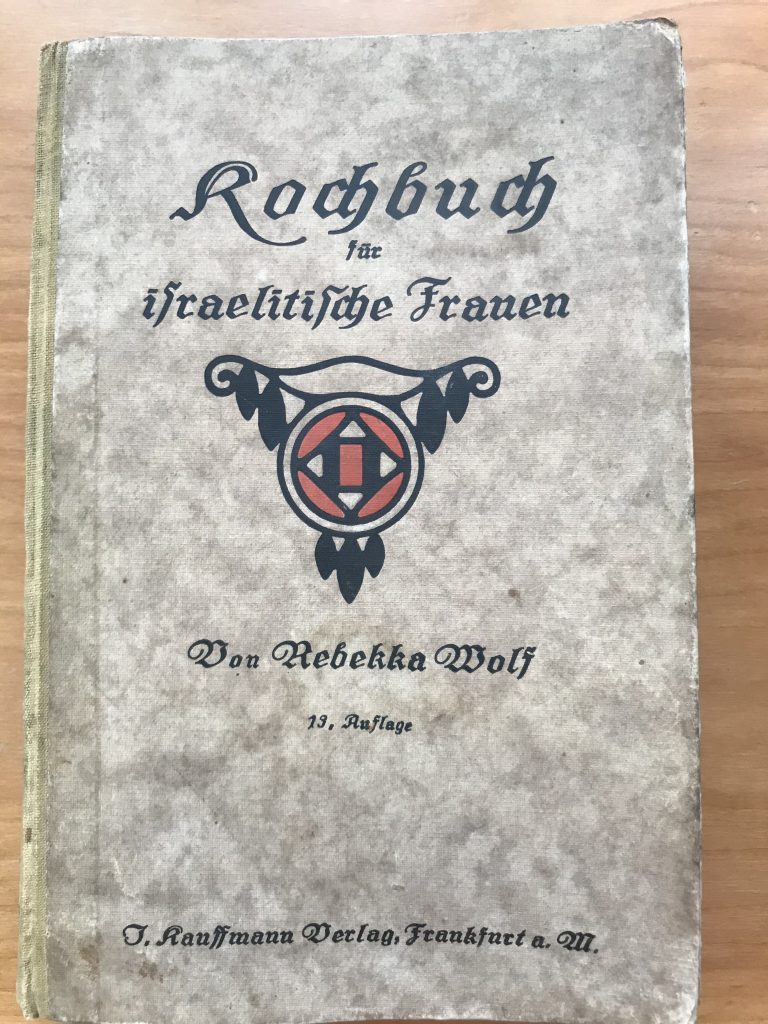

Kochbuch für israelitische Frauen, Rebekka Wolf (born Heinemann). A beautiful little cooking book with additional information on the blessings on shabbat and high holidays and advise on keeping a Jewish household. Also advise on making meat kosher. A special chapter is dedicated to the food on Pesach.

Can you tell us a bit more about the educational programs created by the museum?

The educational programs are directed for Norwegian student from 12 -25 years old. The Jewish Museum of Trondheim offers a variety of teaching programs for primary school, high school and college/university.

- “Norwegian-Jewish traditions, rites and culture”: An educational program which encourages active learning through activities with, for example, ritual objects. The pupils get to research the synagogue and study the similarities and differences between a synagogue and other places of worship. Through this learning resource, pupils will learn about Jewish symbols, holy days and traditions. If desired, pupils can learn about kosher foods. Educational films, which give an introduction into how Jewish holidays and ceremonies are celebrated in Norway, will also be shown.

- Home. Gone. The Jews from Trondheim: This program gives pupils an introduction to the history of the Jews from Trondheim and what happened in the city during the Second World War. By exploring the exhibition and the application, pupils will gain knowledge of Norwegian-Jewish history. The history is told through individuals and family histories. By doing this, the Jewish history becomes more concrete and alive. Pupils will also gain first-hand experience of historical source material which gives an insight into Norwegian war history.

- Nothing is as it seems – conspiracy theories and source criticism: Conspiracy thinking throughout world history has had catastrophic consequences, such as ethnic cleansing and genocide. Social media has made it easier than ever to spread conspiracy theories. In order to evaluate which information is reliable, you need skills in source criticism. This educational program makes use of film, websites and group activities in order to show pupils what characterizes conspiracy theories, and how we can identify them.

- Jewish footprints in Trondheim – Guided Tour: A historical journey through the downtown of Trondheim. Over the course of two hours, the guide will lead the pupils around central points in the city where Jewish families from Trondheim lived and worked. Through the guided tour, the pupils will get to know the Jewish history of the city, from when the Jews migrated to Norway in around 1880, through to the Second World War and up to the present day.The guide will have objects such as photographs and letters which belonged to the people who lived at the different addresses along the tour route. The tour gives the pupils an opportunity to reflect on ethical questions linked to human worth and attitudes, in addition to questions about how it is to be a refugee and immigrant in Norway in today’s society.