In the eighteenth century, the area around the Place Saint Paul was known as “the old Jewry”. Until the first years of the twentieth century, the square itself bore the name Place des Juifs. The narrow streets here are best explored on a Sunday morning, when everyday Jewish life has resumed after the Shabbat.

Rue Pavée is a few yards from the Saint Paul métro station. This is the pletzel, which is yiddish for small square. In this street, which runs perpendicular to rue des Rosiers, stands a surprising registered historical building in the “nouille” (noodle) style. This is the synagogue designed in 1913 by Hector Guimard, then the leading exponent of Art Nouveau, who is responsible for Paris famous métro entrances.

Jews have lived on rue des Rosiers since the middle ages. When Charles VI expelled them from his kingdom, the street fell empty -or so it seemed. That the newly emancipated Jews came back in this same street after the French Revolution, some 400 years later, had led historians to suggest that Jewish families went on living here in secret during the intervening centuries. Thus, when the edict was revoked, it was natural for many of the returning Jews to join fellow believers.

Another world

“You cross the bridge, turn right behind the Hôtel de Ville, and there you are in another world. The street is too narrow, the houses too tall, and all of them cracked. Between the shops you glimpse gloomy courtyards with gloomy lights at the back. There are Hebrew words on the posters, on the signs, and even on the labels of the bottles in the wine merchant’s window. The secondhand man buys up old newspapers, rags, crusts of bread, metals, and tailors’ and cap-makers’ offcuts.”

Edmond Fleg, L’Enfant Prophète (The Child Prophet), Paris, Gallimard, 1926.

In all likelihood an oratory was built on the upper floor at 17 rue des Rosiers a few years before the French Revolution. Unfortunately, the relevant archives were destroyed during the Nazi occupation.

Today, in spite of its many luxury stores, rue des Rosiers remains an important center of Parisian Jewish life with its bookstores, especially the Temple Bookstore, the main reference with the mahJ’s library for books concerning Judaica. Among the many restaurants, we can mention Miznon.

Many Jewish moneylenders lived on rue des Écouffes. In old French, escouffe was the word for a bird of prey, the kite, which was the symbol for pawnbrokers. The street name thus recalls the financial professions to which Jews were limited by the authorities.

Until the beginning of the twentieth century, rue Ferdinand Duval was called “rue des Juifs” (Street of the Jews). Realizing that this moniker might be offensive, City Hall renamed it Ferdinand Duval, after a prefect of Paris.

The Hôtel de Saint Aignan, a superb seventeenth century mansion, now houses the Museum of Jewish Art and History (Musée d’Art et d’Histoire du Judaïsme) remarkable both for its collections and for its ambition. The museum is the fruit of a three way cooperation between the City of Paris, the Culture Ministry and community institutions. Items amassed by the conductor Isaac Strauss in the nineteenth century form the basis of the museum’s collection. Like his Viennese namesakes, the French Strauss composed waltzes that were popular with Second Empire society. His success soon reached beyond French Second Empire ballrooms and, on his travels around Europe, this keen student of Jewish history set out to acquire ritual objects from every period. In 1890 his remarkable collection was bought by Baroness Nathaniel de Rothschild, who donated it to the state. The museum also houses the objects formerly exhibited at the Musée d’art juif. Now closed, this museum was established in Montmartre at the end of World War II and contained wooden models of Polish synagogues made by students of the ORT trade school. In addition, the museum has the collections of the Consistory of Paris (Torah crown, Galicia, 1810) and those of the Fondation du judaïsme français, plus its own acquisitions (The Jewish Cemetery, a painting by Samuel Hirszenberg from 1892).

Our interview with Paul Salmona, Director of the mahJ, who tells us about the history of the museum and its great moments. He also presents the current exhibition dedicated to Pierre Dac and the museum’s future projects.

Jguideeurope: What is the origin of the choice of place to host the mahJ?

Paul Salmona: The idea of a museum of Judaism in Paris is quite old, but it crystallized in 1980 with the exhibition at the Grand Palais of masterpieces from the Jewish collection of the Musée de Cluny.

The project then took shape with the search for a place. Claude-Gérard Marcus, an elected official from Paris, convinced Jacques Chirac to make the Saint-Aignan hotel available, acquired by the city in 1962 as part of the Marais safeguard plan. At the same time, Jack Lang undertook to co-finance the project and to deposit the Cluny collection there. A prefiguration association was created in 1988 and ten years later the museum opened under the aegis of Laurence Sigal, the first director. It made sense to install it in this aristocratic palace occupied from the 19th century by workshops of furriers, tailors, cap makers and hatters, halfway between the rue des Rosiers and the synagogue of Nazareth, in a neighborhood which welcomed waves of Jewish immigration from eastern France, then central and eastern Europe. A work by Christian Boltanski recalls this story in a work entitled “The Inhabitants of the Hôtel de Saint-Aignan from 1939” and installed in a courtyard.

Can you tell us about some particularly striking moments in the mahJ?

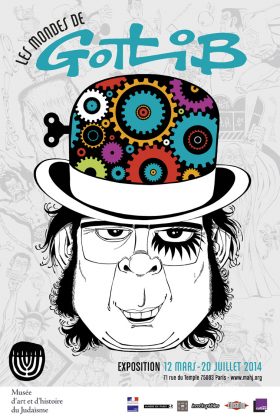

There are so many in 22 years of intense activity. Among the acquisitions, mention should be made of the donation of the 2,600 archives of the Dreyfus affair by the captain’s family, or the purchase in 1988 of the Austrian soukkah, Laurence Sigal’s first acquisition against payment; we can mention the gift of the Columns of Guerry by Georges Jeanclos by the artist’s family, the purchase of 435 old photographs by Helmar Lerski thanks to a public subscription… Before taking up my post, I was very marked by the he exhibition “Future Futur” which revealed to the French public the avant-garde of the years 1914-1939 which aspired to create a truly Jewish modern art by drawing on the traditional folk art of Yiddishsland. Another example is the Golem Exhibit, which showed how this myth permeates the West even though few people know that it was originally a Jewish legend. The Charlotte Salomon exhibition was a real discovery for the public, which had as its posterity the reissue of Vie? Ou théaâre? by Le Tripode, a huge success for an art book of this ambition. I am also thinking of the self-portraits of Arnold Schönberg, which were little known and whose exhibition made a big impression on the public. The mahJ has also given a good place to the 9th art with “From Superman to the Rabbi’s Cat” and “The worlds of Gotlib” or “René Goscinny, beyond laughter”.

Can you think of another place related to Jewish cultural heritage that is important to you personally and that deserves to be better known?

I am thinking first of the synagogue of Cavaillon, built in the middle of the 18th century on the site of the medieval synagogue. Very rococo style, it is well highlighted by its recent restoration. It is the witness of a vanished world, that of the Comtadin Jews, which had survived the medieval expulsions but disappeared with the Emancipation and the departure of these rural elites to the big cities. I am also thinking of the medieval Jewish monument of Rouen, discovered by chance in the courtyard of the Palais de Justice in 1976.

It is the oldest Jewish archaeological remains in elevation, dating from the end of the 11th – beginning of the 12th, whose architecture has the same qualities as those of contemporary Romanesque churches. After the discovery, it had been covered by a hideous slab of concrete, hampering its conservation and complicating its visit. It is a place that bears witness to the importance of the Jewish presence in France before the expulsions of the late 14th century. It is also located rue aux Juifs, a toponym that recalls the central place of Jews in cities in the Middle Ages in France. Recent archaeological research tends to show that this building was a synagogue. Benches were found on the first floor with a “header” stone at the bottom which probably supported the holy ark.

We were previously talking about these disappearing places of Jewish cultural heritage. Conversely, the mahJ has an expansion project. Can you tell us more?

The mahJ currently has a permanent course of 1000 m² dating from the 1990s, which is insufficient. We have an ambitious but realistic extension project under the Anne Frank Garden. It will make it possible to gain 1,000 m², and create rooms of 550 m² for temporary exhibitions. As for the current temporary exhibition rooms, they will allow the permanent exhibition to be extended to an additional 400 m². The route will start with the Jewish presence in France in Antiquity (essential for schoolchildren) and will continue with the height of Franco-Judaism in the interwar period, the rescue of the Jews during the Occupation, the reconstruction of Judaism in France after 1945 and the contemporary collection. It is an 18 M € project which benefits from the financial support of the city of Paris and the State for two thirds. We are therefore looking for € 6 million from private donors. We hope to open in 2025 in a completely renewed museum.

The visit starts on the first floor with the fundamental texts and symbolic objects. The rooms that follow reveal the diverse facets of Judaism. The medieval Jewries are represented by tombstones discovered in the nineteenth century when boulevard Saint Germain was built. Italy and its ghettos are represented by liturgical furniture (a circumcision chair [Kisei shel Eliyahu] from the early eighteenth century), silverware, and embroidery. Amsterdam, London and Bordeaux are evoked by objects and prints (a painting by Jean Lubin Vauzelle of the synagogue at Bordeaux, 1812) that exemplify integration of the Jews cast out of Spain. Considerable space is devoted as well to the celebrations that punctuate the Jewish year: Purim rolls, Hannukah lamps, a nineteenth century Austrian sukkah decorated with a view of Jerusalem.

Two sections, the Traditional Ashkenazic World and the Traditional Sephardic World, offer overall artistic and religious views of these two main ritual communities. A sequence entitled “Emancipation: The French model” offers a historical vision from the French Revolution onward (an 1867 painting by Edouard Moyse shows the Great Sanhedrin of Paris), highlighting key moments of integration. The Jewish presence in twentieth century art presents works from the early decades of the last century. Underlying these runs the eternal question of Jewish expression in art through folklore, ornament, biblical sources and calligraphy.

The Shoah is commemorated by a kind of memorial, a break in the sequence. Last, this impressive complex has temporary exhibition rooms for contemporary artists, an auditorium for concerts, talks and film screenings, a library, a photo library, a video library, and a tearoom.

The Memorial to the Unknown Jewish Martyr (Mémorial du Martyr Juif Inconnu) was built in 1953 by international subscription on land made available by the municipality. The facade presents texts in French, Hebrew, and Yiddish in remembrance of the victims of the Shoah. In front of the building, designed by the architects Georges Goldberg and Alexandre Persitz, there is a symbolic basin inscribed with the names of the main Nazi camps and the Warsaw ghetto. It serves as a light well for the underground crypt with its perpetual flame. The upper floor os the building has rooms for temporary exhibits on the war and its genocide. The Center for Contemporary Jewish Documentation (CDJC) library and archives are wholly dedicated to the Nazi period.

As you walk toward the Place des Vosges, you’ll find on this beautiful place the Charles Liché Synagogue, built in 1963 and named after its founder and rabbi. One street behind, there is the Synagogue on rue des Tournelles. The original building, from 1861, was burned down during the Paris Commune of 1871. It was rebuilt following a design by Marcellin Varcollier in a style close to that of the synagogue on rue de la Victoire. The facade features the Tablets of the Law and the Paris city coats of arms. Consecrated in 1876, this synagogue has a visible metal inner structure built in the workshops of Gustave Eiffel more than ten years before his famous Tower. The two rows of galleries, made entirely of iron and cast iron, provide both support and ornament.

The Saphir Gallery has been an essential part of Jewish artistic life for nearly half a century. It is above all the work of Elie and Francine Szapiro. A couple involved in (re)discovering and sharing a cultural heritage that refuses to be lost, despite the blows of history. Confirmed artists and revelations, so many were exposed on the first floor of the gallery or in the basement which is an architectural work in itself, dating back several centuries. Francine Szapiro welcomes us, evoking the genesis of the gallery, but also its contemporary role. In particular in the context of the European Days of Jewish Culture, with the exhibition “Plastician struggles: tribute to Ukraine”.

Jguideeurope: How was the Saphir Gallery born?

Francine Szapiro: In 1979, I was a journalist with a passion for art, working for the Ark, the Jewish Telegraphic Agency and other media. My husband was a doctor with a passion for history and a founding member of the French Commission for Jewish Archives. In this period of Jewish cultural reconstruction, we had the common dream of opening a gallery where all aspects of this culture would be presented, its manifestations, ritual objects and ancient books… without enclosing it in a ghetto, motivated by the desire to show the reciprocal contribution of the surrounding cultures.

Who were the first artists to be exhibited?

There were so many! My husband and I were passionate about sharing our favorites and discoveries in a place where we could meet and exchange. And the dream finally came true. Our first gallery was located on the boulevard Saint-Germain, and was inaugurated by Elie Wiesel with an exhibition on postcards and Judaism to show the diversity of the Jewish world. We began by exhibiting Alain Kleinmann, then Shelomo Selinger. This small 15 m² gallery has hosted many other large events since then.

How do you perceive the evolution of interest in Jewish art?

I would love to be able to sit down one day and tell this story in detail. My husband and I were part of the generation that wanted to rebuild a heritage that had been destroyed or dispersed during the war. We knew at the time great collectors like Victor Klagsbald, who is the father of Laurence Sigal, the former director of the mahJ. In the aftermath of the war, these collectors searched everywhere for evidence of Jewish life in the past, at the flea market or in other sales places. My husband organized the first international judaica sale. People then realized that it could have a market value, and saved pictorial and written objects from loss and destruction. Thus, we have seen two generations in the gallery. The one of those who wanted to reconstruct the dispersed life, then the one who wished to affirm its insertion in the century, the will of integration and assimilation, moving away a little from this quest at all costs of traces. This did not prevent some young people from being very interested and involved in the search for the Jewish cultural heritage. This desire was particularly evident during the European Days of Jewish Culture. This European desire to gather is very important. We have had the pleasure of participating in these days since the beginning.

During the EDJC 2022, Ukraine was in the spotlight at the Saphir gallery.

We presented the exhibition “Plastician struggles” just before the summer with various artists that we will resume. Among them, the writer Hubert Haddad who we discover as a painter impregnated with Kabbalah or Bruno Edan, artist who died in 1981 at the age of 23 and to whom the art historian Delphine Durand has devoted a magnificent monograph. Three artists of Ukrainian origin also participate. Serge Kantorowicz, who was a refugee in France during the war, and who lost a large part of his family in Ukraine during the Shoah.

He rebuilt himself through painting, working in the Maeght studios where he made friends with great artists. Sam Szafran is his cousin. Serge has developed a very poetic and personal world that leaves the traditional representations. We also welcomed to the gallery the work of Igor Pototsky, a Ukrainian refugee we met recently, considered a great writer, poet and illustrator. And finally the young Ukrainian artist Yana Bystrova. This artist is going through difficult times, not knowing what happened to her works that were left in Kiev for an exhibition. Many Ukrainian artists and writers come to us, souls in pain who try to find links. Other artists are presented during this exhibition.

Among them, Sergio Birga, who died a year ago. A Florentine who went to meet the great German, Austrian and Belgian expressionists who had survived the Holocaust. He immersed himself for 50 years in the world of Kafka, building a very expressionist work around the writer. Birga was also a great wood engraver.

So we wanted to break down the fields of creation between engraving, sculpture, painting and even photography. By presenting, for example, the works of the contemporary photographer Jorge Amat, author of a beautiful film on Serge Kantorowicz and many others on art and cinema. Not to mention the work of Michel Kirch, son of a rabbi, whose work is the testimony of a quest for identity and spirituality.

The gallery is above all a place of encounters, reunions and sharing of a Jewish culture, and in the context of this exhibition it celebrates the vitality of a fighting Ukraine.

Saphir Gallery, 69 rue du Temple, 75003 Paris