It’s a strange feeling when you arrive in Drancy. The former internment camp and the Shoah Memorial opposite it are located near the junction of the avenues Jean Jaurès and Henri Barbusse. The town of Drancy, in the Seine-Saint-Denis department, is home to a large number of shops, cafés and markets.

Would it be a challenge to push open this door, to enter this memorial and discover the painful history that took place there? Especially with so many traces of the U-shaped buildings that made up the camp still very much in evidence.

The Drancy Shoah Memorial does not wait for visitors to open its doors. It builds bridges between the past and the future, organising numerous themed and educational workshops, school meetings, cultural events and temporary exhibitions, in addition to its permanent exhibition. The aim is to preserve the memory of the past and facilitate its transmission, particularly to young people.

Drancy is located to the north-east of Paris. It can be reached either by car or by taking the RER or metro, then a bus. 200 metres from the junction of avenues Jaurès and Barbusse, past the gymnasium, you come to the site of the cité de la Muette , which became the Drancy internment camp.

It surrounds the esplanade renamed Charles de Gaulle after the war in tribute to the general who rose up against the collaborationist Vichy regime with his appeal from London on 18 June 1940, refusing to surrender France. The plaque was installed in 1990.

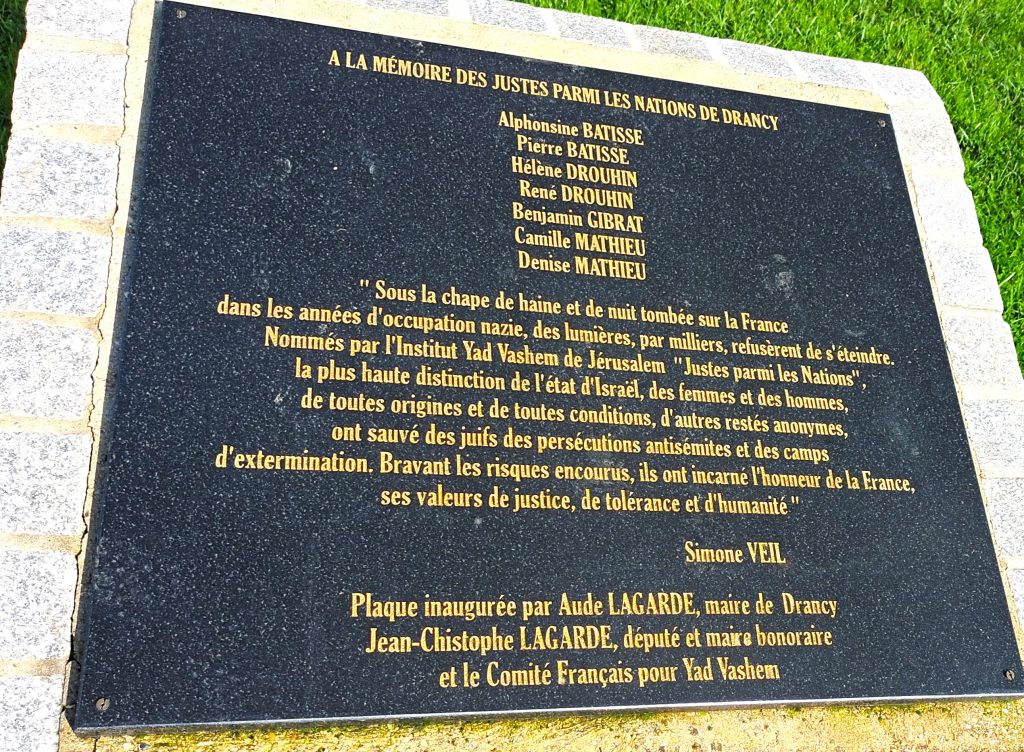

Next to it, a plaque pays tribute to the Righteous Among the Nations of Drancy: Alphonsine Bâtisse, Pierre Bâtisse, Hélène Drouhin, René Drouhin, Benjamin Gibrat, Camille Mathieu and Denise Mathieu. Beneath these names is a quotation from Simone Veil, the survivor of the camps and a symbol of courage and resilience through her personal and political life. The plaque was unveiled by Aude Lagarde, Mayor of Drancy, and MP Jean-Christophe Lagarde.

The Cité de la Muette was built between 1930 and 1937, with the aim of providing a ‘modern’ form of collective housing, on the initiative of the Office départemental de l’habitat. In July 1940, the building was requisitioned by the Germans to house French and British prisoners of war.

The Drancy camp was emptied of prisoners of war in July 1941 in preparation for the second round-up of Parisian Jews. More than 4,200 Jews, all men, were arrested and interned at the Drancy camp. As the plaques on the outside wall of the building on the right remind us, 63,000 of the 76,000 Jews deported from France between 1942 and 1944 were sent to Nazi extermination camps from Drancy.

Following the Liberation, from September 1944, the camp was used as a prison for people suspected of collaboration. The cité de la Muette was then adapted to accommodate housing, which were rented starting in 1948.

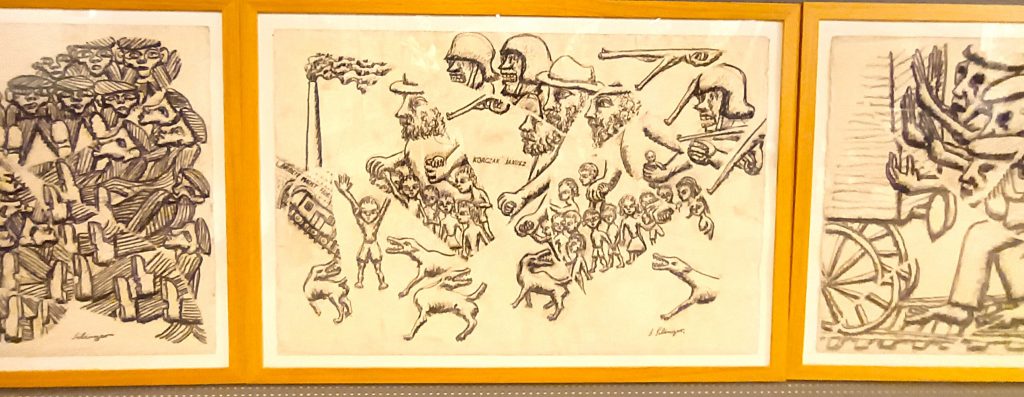

The Drancy monument was erected much later, in 1976, at the instigation of a committee led by Maurice Nilès, mayor of Drancy and a former Resistance fighter. It was created by the sculptor Shlomo Selinger. Born in Poland in 1928, he was deported with his family in 1942. He survived many concentration camps, but his parents and other members of his family did not.

He migrated to Israel, where he learned drawing and sculpture. He continued his training at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris in 1956. He went on to create hundreds of works. In 1973, he won first prize in the international competition launched to create the Drancy memorial. Following this, he took part in a number of meetings with schoolchildren, sharing his story and the love of life that helped to build his resilience.

The memorial wagon, located near the memorial, was installed in 1988.

The Drancy Shoah Memorial was built on the initiative of the Fondation pour la Mémoire de la Shoah. Located opposite the cité de la Muette, it was designed by architect Roger Diener and inaugurated in 2012 by French President François Hollande.

The basement of the Shoah Memorial building in Drancy houses temporary exhibitions. The documentation centre is on the first floor, with educational rooms on the second floor. The permanent exhibition is on the third floor.

As you enter, you’ll see a series of videos on the left and a chronology of the site since it was built in 1931 on the right. Each video lasts several minutes, recounting different moments and aspects of the history of the Drancy internment camp through images and personal accounts. The films for the ellipse and the exhibition as a whole were directed by Patrick Rotman.

The first video focuses on the roundup of 20 August 1941 and the arrival of the first Jewish internees at the Drancy camp. It shows how the gendarmes sealed off the 11th arrondissement of Paris, where many working-class Jews were living at the time. Testimonies, in particular that of a man who explains how on that day a gendarme asked him to put his bike on the side and get on a bus with others, without knowing that his destination would be Drancy.

The 2nd video shows the dramatic beginnings of the Drancy camp. The 3rd video is entitled ‘Transit camp for French Jews, the last stage before deportation’. It shows how they were brought to Drancy, a place whose construction was not completed and therefore not ‘functional’. Initially, a large number of them were crammed into rooms, prevented from doing anything except certain humiliating chores, administered by the Nazis and guarded by the gendarmes.

The 4th video is devoted to the administration of the Drancy camp, with the three camp leaders, Theodor Dannecker, Heinz Röthke and the infamous Aloïs Brunner. To raise the level of brutality even higher, Brunner placed the French gendarmes outside the camp and had the Viennese SS impose order with an iron fist. The 5th video is devoted to the Austerlitz, Levitan and Bassano labour camps, where Jews were placed to sort the looted goods of the Jews.

The 6th video focuses on the Rothschild hospital, which was transformed into a prison hospital and housed Jewish inmates suffering from serious illnesses. This did not prevent roundups, in particular one in which the German authorities came and took away many of the sick, even people who had undergone major surgery the day before.

The 7th video is entitled ‘Friends of the Jews and Righteous from the Drancy camp’. It shows young men and women, most of them in their twenties, imprisoned at Drancy and required to wear the words ‘friend of the Jews’ on their jackets, as they were accused by the authorities of having come to the aid of their fellow Jews or simply having opposed the wearing of the yellow star. Some of them marked their stars ‘Auvergnat’ or ‘Breton’ and even in jazzy ‘swing’ mode to make fun of this discriminatory measure. In the camp, these Righteous continued their rebellion, discreetly trying to help the Jews, as did a handful of gendarmes guarding the camp.

The last video focuses on the fate of children in the Drancy camp. At first, the prisoners were men. From August 1942, women and children were also deported. The video gives the floor to men and women, children at the time, who recount the conditions of survival in the Drancy camp. The way in which the adults organised schooling for them, using notebooks received in parcels, to do homework and dictate. And the struggle against despair, particularly when a lady began to sing in a barrack room, the children listening with emotion and enjoying this moment imposing a shade of color on the camp. Most of the children interned at Drancy between 1942 and 1944 were deported.

Opposite the videos is a chronology of the Drancy camp. It describes the construction of the La Muette housing estate, the imprisonment of prisoners of war and then that of the Jews rounded up.

The first Paris roundup, known as the ‘Green Ticket’ roundup, took place in May 1941. 3,700 Jewish men were taken to the Pithiviers and Beaune-La-Rolande camps in the Loiret region. The Drancy camp was emptied of prisoners of war in July 1941 and the more than 4,200 Jews arrested during the second round-up, all men, were interned in the Drancy camp. There they were placed under the responsibility of the Prefecture of Police and guarded by the gendarmerie.

The terrible living conditions and especially the threat of starvation provoked anger among the first internees. They were then allowed to receive parcels of food and clothing, but these were searched and often confiscated by the gendarmes keeping watch. A black market was created. One person testifies in a video how, as a child, he remembers that a gendarme had sold a packet of cigarettes at an exorbitant price to a detainee and that on the same day another gendarme stole the packet from him during a search in order to resell it the next day.

Following around thirty deaths, a German military medical commission released around a thousand patients between 4 and 7 November 1941. On 22 June 1942, the first deportation convoy left the Drancy camp for the Auschwitz concentration camp. On 16 and 17 July 1942, following the Vel d’Hiv round-up, almost 2,000 men and 3,000 women were sent to the Drancy camp. Heinz Röthke took over from Theodor Dannecker. From 14 August 1942, children were also deported.

In June 1943, Aloïs Brunner, an SS captain, became camp commander. The last large convoy of deportees left for Auschwitz on 31 July 1944. The labour camps annexed to Drancy opened their doors during this period. The Lévitan camp, located on the Faubourg Saint-Martin in Paris, opened on 10 July 1943, the Austerlitz camp on 20 October 1943 and the rue Bassano camp on 15 March 1944. On 17 August 1944, Aloïs Brunner fled before the advance of the Allied forces and continued deporting Jews from territories still controlled by the Nazis.

At the far left of the permanent exhibition, paintings depict this daily life. These are by Jane Levy, a woman from an Alsatian Jewish family who was born in Paris in 1894 and studied at the Ecole des Arts Décoratifs. She was arrested in November 1942, interned in the Drancy camp and deported with her brother Albert to Auschwitz on 31 July 1943. In her paintings, we discover the barracks with the clothes hanging on the beds and the saucepans lined up next to them. There are also works by Georges Horan, born in St Petersburg in 1894. An industrial draughtsman, he was interned in various camps, including Pithiviers and Drancy, and liberated on 13 March 1943. 56 prints have been collected in which the painter depicts the daily life of the prisoners.

Alongside these paintings and drawings, a model of the camp has been reconstructed, showing each entrance and the guard posts, toilets and other areas, including the stairways leading to deportation. It shows that the Drancy camp consisted of 5 blocks with 22 staircases. Blocks 1, 2, 4 and 5 contained eighty rooms. The internal layout of block 3 changed from period to period.

At the far right of the room, panels show the itinerary of the main deportation convoys: the bureaucratic process, and the departures from Drancy. How it was carried out by the Nazi authorities in collusion with collaborators. The methodical preparation of the convoys, with the names of the people on the files that were sent, the establishment of the list of deportees. Also the timetable for all the convoys. The section of the exhibition devoted to the deportations ends with the faces of convoy 71, which left Drancy on 13 April 1944. Photos of the children and letters written and thrown from the train recount what happened to them and try to alert the population.

A small white room, just next to the section devoted to the deportation, has two benches where visitors can sit and listen to a series of letters from prisoners being read out.

Opposite the entrance to this room are objects belonging to prisoners. These include a bag embroidered with the words ‘Grunman Lieba, escalier 20, chambre 11, bloc 5, matricule 38 32, Drancy’. There is also an armband with a deportee’s number, the number 239 of Léa Darcis and other everyday objects.

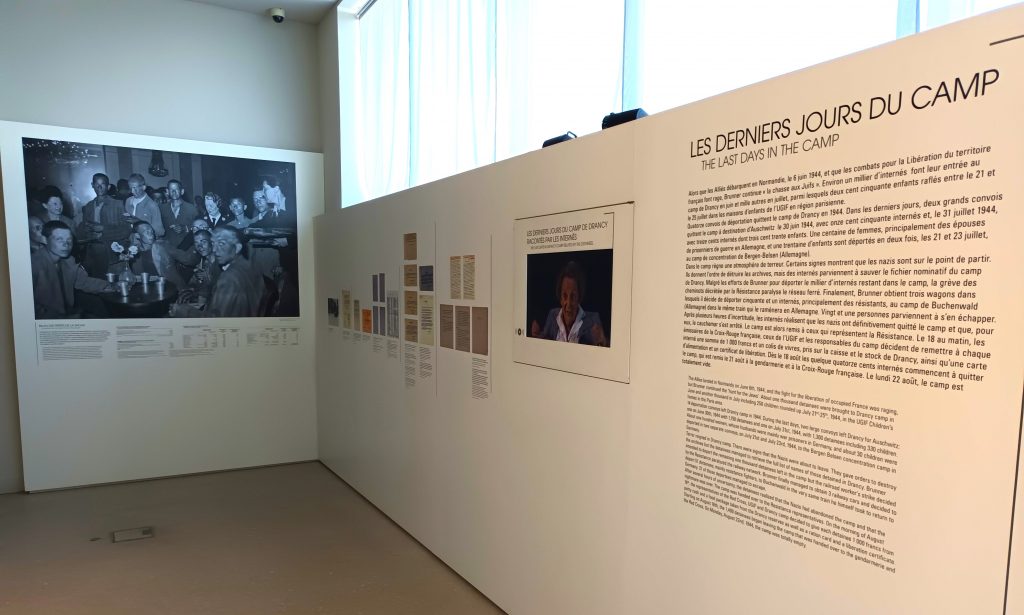

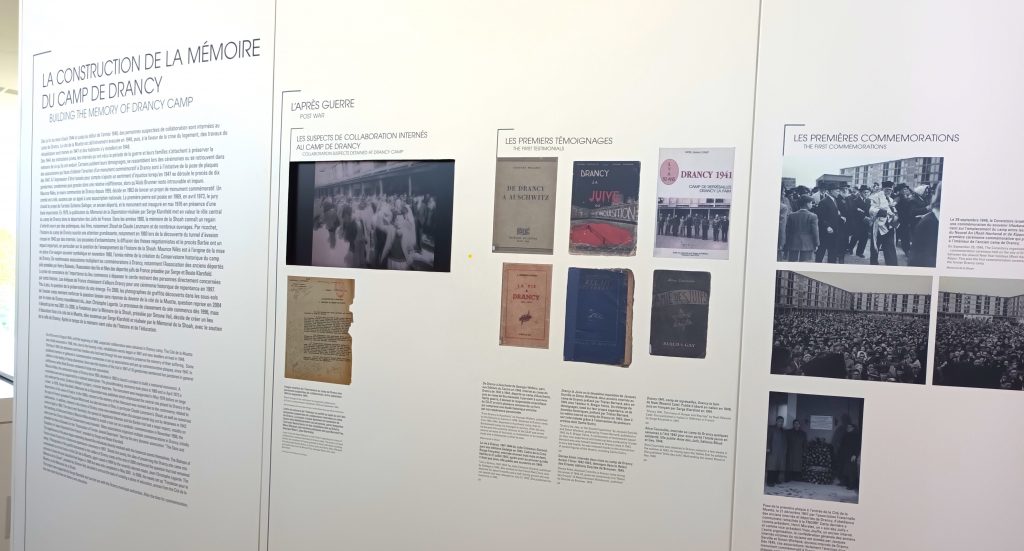

The exhibition ends at the entrance on the left, with panels describing the last days of the camp, with numerous testimonies and documents, as well as the death toll from the Shoah. This is followed by the work of remembering. It shows how the site was rehabilitated following the Liberation. First for people suspected of collaboration, then for the tenants when the renovation work was completed in 1948.

The first testimonies of survivors of the deportation were also published and shared. But, unfortunately, as Simone Veil recounts in her autobiography, at first these were words that were virtually inaudible, as the time had come to tell stories of the Resistance in order to restore the nation’s image. Many survivors of the Shoah also chose to remain silent, rebuilding their lives, so as not to be confronted with the immense wave that was too close and threatened to overwhelm their survival. The main aim of this Jewish resilience was to create the best possible life for the next generation, to take revenge on ‘fate’ and to help create a fairer society.

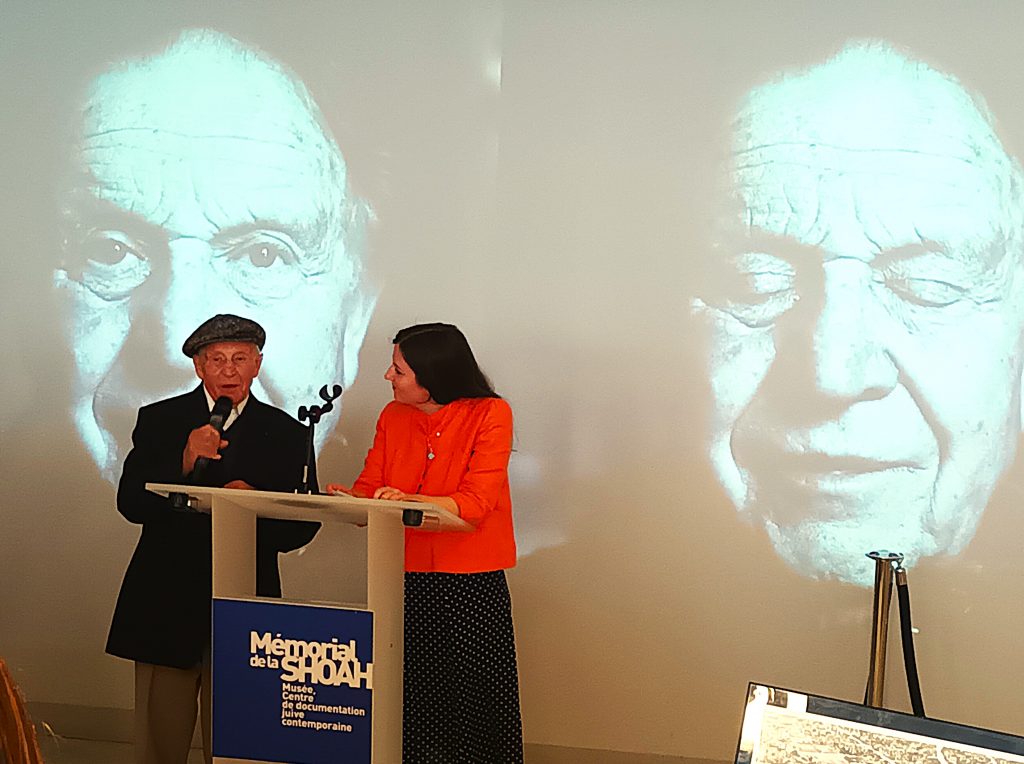

A magnificent exhibition dedicated to the work of Shelomo Selinger is presented in 2025-6. The opening took place in the presence of the artist and his wife Ruthy Selinger. Sixty works, some of which have never been seen before, pay tribute to the victims of the Holocaust, in particular the heroines Mala Zimetbaum, Zivia Lubetkin and Haika Grossman.

But also to Janusz Korczak.

An important memorial work. Also present in Selinger’s paintings is an ode to the celbration of life, this Jewish revenge of the aftermath on the death desired by various totalitarian regimes.

Interview of Eléonore Ward, Head of the Memorial Museum of Drancy

Jguideeurope: On 23 October 2024, you organised an Open Day for teachers. Do you feel that there is a very strong awareness among teachers of the contemporary importance of sharing the history of the Shoah?

Eléonore Ward: Yes, this awareness is real: the last witnesses are disappearing, discrimination in the broadest sense is at a very high level and this year we are commemorating the 80th anniversary of the liberation of the camps. But above all, and more generally, this history is taking its rightful place in the school curriculum. It is studied three times in the course of a child’s schooling: in CM2, teachers introduce the concept and deal with anti-Jewish persecution and in particular the special fate of hidden children. In 9th grade, pupils acquire many more keys to understanding the Second World War (the mechanisms of anti-Semitism, Nazism and the collaboration of the Vichy regime). Later in high school, the study becomes increasingly in-depth, with the added challenges of remembrance and the historiographical approach.

So we’re seeing a huge demand from teachers, and not just in history-geography. We have developed a very diverse range of teaching resources, covering a wide range of subjects such as artistic and cultural education, media and information literacy, citizenship and so on. In addition to this range of courses, teachers can receive training so that they are more at ease with the content when they return to the classroom. Coming to Drancy gives pupils a unique opportunity to understand what happened through a concrete, material place: the historic site of the former Drancy camp, now the Cité de la Muette.

What programmes does the Drancy Memorial organise for young people?

The educational programmes offered by the Shoah Memorial are primarily school-based, with teachers of history and geography as well as literature, music and other subjects. Most classes take part in an hour and a half guided tour or a 2 to 3-hour educational workshop that includes a guided tour. These workshops take things a step further by getting pupils involved in a range of activities (historical research, debates, artistic creation, etc.).

In addition, we organise multiple events: testimonies from survivors, film screenings followed by debates, meetings with authors, theatrical performances, etc., as well as outdoor remembrance trails to explore local history in greater depth.

Finally, the Drancy Memorial is developing longer-term projects with a more qualitative approach. For example, we meet with pupils on several occasions as part of a project-based teaching approach. In particular, on themes such as how to learn to become guides at Drancy, taking part in a poetry competition on remembrance, taking part in a commemoration ceremony, etc.

As well as schoolchildren, we are also delighted to welcome young people outside school (municipal centres, young elected representatives, civic associations, etc.) and families for film screenings, testimonies or workshops. Don’t hesitate to contact us for more information. Our content is tailored to the needs and characteristics of each group.

How long have you been organising the Drancy Rendez-Vous and can you tell us a little more about this initiative?

The Drancy Rendez-Vous were set up a few years ago. Over the last year, we’ve considerably expanded the offer. The aim is to offer activities for the general public in a variety of formats (conferences, guided tours, workshops, testimonials, screenings, debates, etc.) to help them explore the subject in greater depth. The themes are also diverse: they can be history and remembrance, but also literature, philosophical reflections, film analysis, etc.

In my opinion, the Drancy Shoah Memorial is a place of remembrance, but it is no less alive for that. Such a sensitive subject can also bring together a wide range of people to continue learning together, open up to others and commit to an inclusive society. To find out more, please consult the museum’s quarterly cultural programme. All our activities are free and open to all.

Can you tell us about a memorable encounter with a visitor?

That’s a difficult question to answer! I can think of a number of people, in particular the inhabitants of Drancy who sometimes never dared to open the door, intimidated by the solemnity of the place. I’m also thinking of visitors from the four corners of the world, very moved, in a quest for the truth about their ancestors who spent time at Drancy during the War. But there is one in particular that stands out in my memory, that of Victor Gotajner, interned for a few days as a child with his mother. He came back to Drancy for the first time in his life, at the end of 2024, and he had tears in his eyes. After a few discussions, I invited him one Sunday to share his story with the public. It was a very powerful moment for everyone.