The traveler Benjamin of Tudela visited Montpellier in 1165. In his travel diaries, he noted the existence of Batey midrashot kevouot le-Talmud in the city. In addition to these intellectual activities cited in a Hebrew source, Latin documents relate the presence of Jews in trade between Agde, Narbonne and Montpellier. They had a monopoly on silks and fabrics. Representatives of the Mosaic Law were also involved in the effort to protect the city.

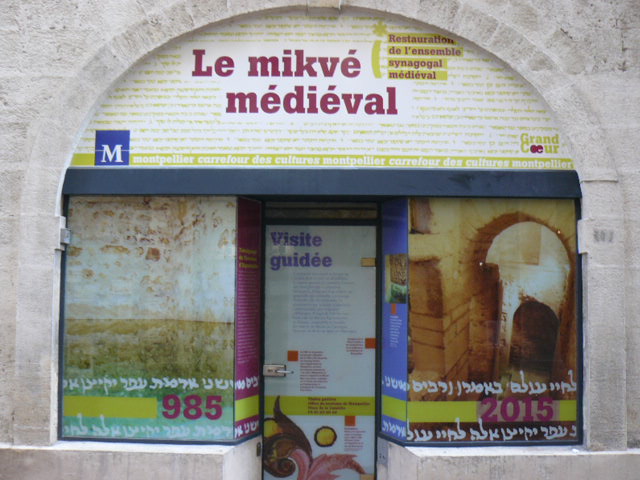

The current rue de la Barralerie is the old central street of the Jewish quarter in the seigneurial stronghold of Guilhem. The religious complex includes a place called synagogal, a house of alms (domus helemosine), a house of studies, and the medieval mikveh , which has been found and restored, all components of the Schola Judeorum; it can be visited at n ° 1 on the street. We can see the 12th century bath having escaped the roughness of time, the undressing room, as well as the basin with its seven underwater steps and its wall orifice decorated with a gargoyle (the first two deepest are from medieval times). A jewel of Romanesque art, made by Christian architects at the request of the Jewish community, it is one of the two oldest religious monuments in the city.

Visible with the Montpellier Tourist Office, this hotspot of Montpellier’s memory is part of an exceptional medieval synagogal ensemble which has been the subject of in-depth archaeological excavations carried out by Christian Markiewicz, associate member of LA3M (Laboratory of Medieval and Modern Archeology in the Mediterranean) and the City of Montpellier. Philippe Saurel, Mayor and President of Montpellier Méditerranée Metropole was very involved in these archaeological investigations, which led to the recent update of additional basins, pavements and spaces adjoining the 12th century Jewish ritual bath.

A Jewish quarter open to mixed Judeo-Christian habitat developed in the 13th century, around rue de la Barralerie, with the mikveh, which was, let us remember, re-discovered in the early 1980s, restored, and then inaugurated in 1985, during the millennium of the city by Georges Frêche, on the occasion of the organization by Carol Iancu, professor at the University Paul Valéry Montpellier 3, of an international scientific symposium on “The Jews in Montpellier and in the Languedoc ”.

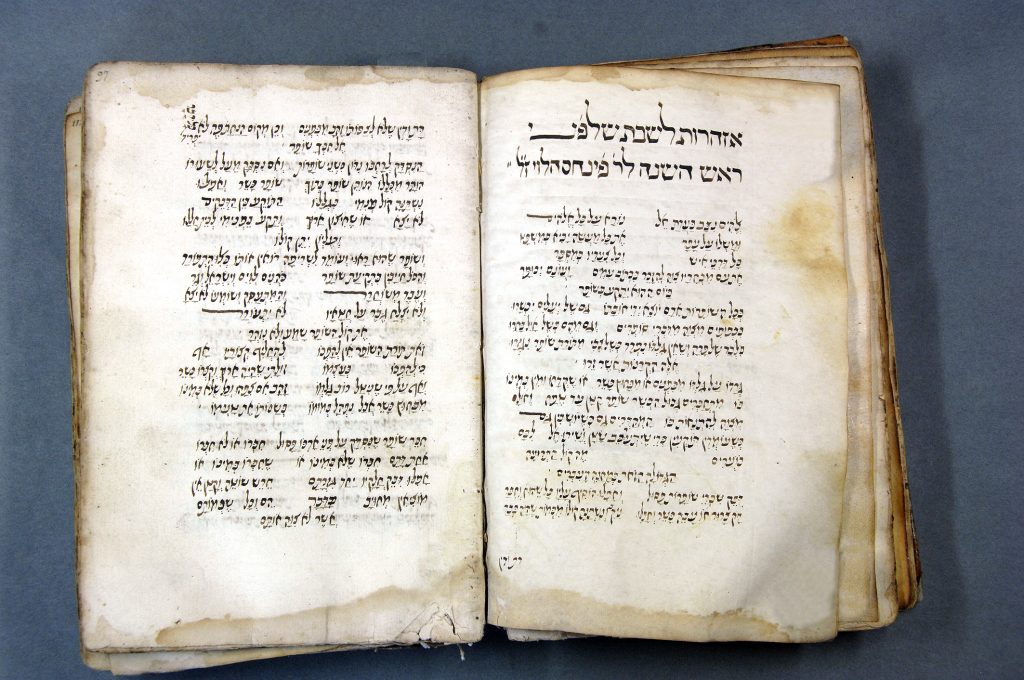

The 14th century was the century of the expulsion of the Jews from France, marked by dismissals (1306 in particular, then 1322 and 1394) and successive reminders (1315; 1359) of the French monarchs. The Jews settle during the last authorized period (1359-1394), rue de la Vieille Intendance very close to the old habitat. Montpellier will have been the scene of famous Maimonidian controversies: a 1st time in 1230, around the writings of RAMBAM: a copy of the Guide of the Perplexed, would have been according to Hillel of Verona, destroyed in public place; a second time around the 1300s against philosophy. Athens and Jerusalem: should we understand the Mosaic law in the light of the Greek sophia? A fideist reading or a reading supported by reason? Intellectual excitement in any case. It is not fortuitous that this takes place in Montpellier, a place of intellectual and theological profusion, and within the Jewish world.

In the 17th century, Jews from Comtat Venaissin had temporary permits to trade in Montpellier.

From 1714, nine Jews settled in the city. Others follow this approach. At the beginning of the 19th century, the Jewish community numbered a hundred people. It was then directed by Moïse Milhau, who represented the Vaucluse department with the Grand Sanhedrin.

Around 60 families made up the Montpellier Jewish community on the eve of the Second World War, or 300 individuals, participating in the celebration of shabbat and festive times; foreign Jewish students (many in medicine) could join them. In 1940-41, and even in 1933 with the rise of Nazism, the installation of anti-Semitism and the introduction of the numerus clausus in the countries of the East (Germany, Hungary, Poland, Romania) is increased by Jewish refugees: 150 homes gathering 750 people, manifested by their contributions, and tangible memberships. A proportion is revealing in this respect, with in 1933, out of 800 French and foreign students registered in medicine, the tenth of Romanian Jewish students amounting to 80!

The place of worship, first located on rue du Jeu de l’Arc, took place on rue des Augustins (now a Protestant temple). Cesar Uziel, of Ottoman origin, who arrived in Montpellier in 1933, first held the office of minister, then that of president of the community, succeeding Leon Brunschwig (died 1934). After him, Louis Kahn will officiate for five years.

In the summer of 1940, refugees from Belgium, Holland, Luxembourg, especially Poland, but also from Alsace-Lorraine and Paris arrived massively in Montpellier. Despite some reluctance, a surge of solidarity is taking place.

With the precious support (obtaining false identity cards) of the Prefect Benedetti, and the Secretary general of the Prefecture of the Hérault Camille Ernst (to which the City recently paid homage), César Uziel (1892-1983) took care of a first group of 250 foreigners, distributed in Montpellier, to the neighboring villages and the hinterland. The main part of this first wave was directed towards Lozère (Lancogne) for a temporary halt.

This does not exclude the whole apparatus of deportations, spoliations (which I have treated widely elsewhere, works in 2000 and 2007), with its harmful lot of denunciations, cowardice, an anti-Semitism erected in State doctrine, the roundups of the fateful summer 42, and internments in the camps of Rivesaltes, and – for the geographical area of Hérault – in that of Agde.

Heroic facts of hope: located in the free zone, Montpellier has served as a refuge for at least fifteen different nationalities, the majority of them Polish (half). The Faculty of Letters welcomed – despite the faux pas of the farrier Augustin Fliche (contrary to the generous attitude of Pierre Jourda) – the great medievalist Marc Bloch before he was shot in Lyon for acts of resistance (1944) ; the Faculty of Medicine was exemplary, thanks to the remarkable action of Dean Giraud (1888-1975) and Professor Balmès (1904-1986) towards hidden Jewish students, defended despite the iniquitous racial laws of the Vichy government, and authorized (“under the cloak”) to take the courses and take the exams.

Throughout these grim years, there are acts of bravery and self-denial of bright men and women who, at the cost of their freedom, risking their lives, saved Jews from the pangs of barbarism. These are the Hassidey Oumot ha-Olam or “Righteous Among the Nations” celebrated by the Yad Vashem Institute in Jerusalem which keeps alive the memory of the six million victims of the Shoah, thereby awarding the “Medal of the Righteous.” Many valiant Montpellier residents have received this high distinction.

At the end of the war, the bloodless Jewish community (about fifty families of Alsatian, Ashkenazi and Turkish origin for the most part) is a mosaic bruised by the Shoah.

In 1946, from rue Marceau to rue des Trésoriers de France, the place of worship of the Association Cultuelle Israélite de Montpellier (ACIM) changed. The Board of Directors, under the direction of César Uziel (who had helped stateless co-religionists fleeing the German advance during the war), acquired the ground floor of a building on rue des Augustins. The synagogue inaugurated in 1952 remained there until 1985, before its transfer to rue Lafon, alongside the synagogue known as Mazal Tov , rue Proudhon. The year 1956 saw the arrival of Rabbi Roger Kahn, whose youthful dynamism changed the community, also following the opening in 1957 of the new Community center on Avenue de Lodève.

The arrival of Jews from North Africa is a historic turning point in Montpellier, as everywhere else in France. Members of the community, all origins combined, accompany these refugees, who have to adapt to countries, Mediterranean certainly, but different in many respects; the newcomers bring a legacy of the warmth of the East, infused with ritual rigor. Their uninhibited and exuberant Judaism revitalizes the community group which remained tenuous.

The arrival of Georges Frêche’s responsibilities was decisive for the Jews. Through his tangible achievements, he becomes a “Jew at heart” for the 6,000 Jews from Montpellier. He left his mark on the Jewish community that was acquired to him.

Let us naturally remember the restoration of the medieval mikveh during the millennium of the city; or even the twinning with Tiberias (where, according to tradition, Maimonides is buried) – already weaving a link between Maimonides and the medieval “City of the Mount” (Ir ha-har, in Hebrew).

In the 1980s and 90s, the development of Montpellier Judaism crystallized around the creation of Radio Juive languedocienne (RJL), today Radio Aviva, co-founded by Carol Iancu to whom we also owe co-discovery of the medieval mikveh of the city, and who also created at Paul Valéry University, the Center for Jewish and Hebrew Research and Studies (1983).

Another offshoot of the Jewish Community and Cultural Center of Montpellier (CCCJ) in 1978 is “The Day of Jerusalem”, an annual popular gathering. The “Jewish and Israeli Film Festival”, which disappeared early, had the merit of dealing with the diversity of Israeli cinematographic creation in a city with a long Zionist memory: there were four Montpellier Jewish delegates to the 1897 Basel Congress, negotiations took place in the prefecture for the departure of the Exodus in Sète.

The 2000s were marked by the creation of a Jewish school and college, as well as the French Committee for Yad Vashem. A generational renewal is manifesting.

Following the discovery of one of the oldest (12th century) European mikvaot, and starting from the observation that in Montpellier, medieval Judaism experienced a golden age until the expulsion edicts of the 14th century, the academics Georges Frêche and the former Chief Rabbi of France, René-Samuel Sirat, created in 2000 the Euro-Mediterranean University Institute of Maimonides (IUEMM) with a view to re-inscribing the medieval figure of Maimonides in the City. The Institute that has established itself in the local cultural landscape is located above the medieval mikveh in the historic Barralerie building where 700 years ago – Jewish passions around philosophical thought clashed.

Developing the history and civilization of Judaism and Israel, fostering interreligious dialogue, constitute the founding axes of this Institute. The room known as “Don Profiat” perpetuates the memory of the last of the Tibbonids.

The Municipality offers since 2008 with the help of the IUEMM and the “New Gallia Judaica”, CNRS team which was integrated in the historic building of the Barralery for a decade, seven didactic showcases for passers-by, which relate the history of medieval Hebrew Montpellier. That is to say if the glorious medieval Jewish history sounds “strong”, as it is said in music, in the “City of Mount”!

Unmissable place of Montpellier, the Maimonides-Averroès-Thomas Aquinas University Institute , whose skills in the daughter religions of monotheism – Christianity and Islam -, were enlarged by Philippe Saurel, Mayor of the City and President of the Metropolis, many events and visitors.

The history of medieval Montpellier and Languedoc Judaism is a story of Judeo-Christian encounters around the Greco-Arab legacy; and also and above all a story of Hebrew passions around Maimonides’ thought and philosophy; passions exacerbated even in the synagogue of the 13th century Jewish quarter, the very place where the Institute is based: a nod to History, undeniable topographical legitimacy.

Page created with the help of Michaël Iancu, Doctor of History and Director of the Maimonides-Averroès-Thomas Aquinas University Institute. Michaël Iancu is the author of Spoliations, déportations, résistance des Juifs à Montpellier et dans l’Hérault, 1940-1944 (Barthélémy, 2000), Vichy et les Juifs. L’exemple de l’Hérault, 1940-1944 (Presses Universitaires de la Méditerranée, 2007) Les Juifs de Montpellier et des terres d’Oc. Figures médiévales, modernes et contemporaines (Cerf, 2014) and texts for the collective works Ombres et lumières du Sud de la France. Les lieux de mémoire du Midi (Les Indes savantes, 2015 et 2016), Nouvelle Histoire de Montpellier (Privat, 2015).

Interview of Michaël Iancu

Jguideeurope : The city of Montpellier is very involved in sharing Jewish cultural heritage. How do you explain this commitment?

Michaël Iancu: Without an apologetic interpretation of local history, it is important to know that in the Middle Ages, Montpellier is not far from having represented an oasis of tolerance, or at least progress in knowledge, in welcoming individuals wherever they came from, opening up to science wherever they came from. Historians have highlighted the privileged place of the city of Montpellier, close to Spain, trading with the Arab world, benefiting from the proximity of Jewish scholars established in Lunel or Béziers.

It is significant moreover that the program of the license in 1309 juxtaposes Galien, Avicenne, Rhazès and Isaac Israeli, in other words the ancient, Arabic, and Jewish medicines of Arabic expression. The Jews were in this “Little Cordoba” that was Montpellier for the medieval period, passers of cultures between Muslim Iberia and feudal Christianity. So, quite naturally, the municipality wanted to find the Jewish roots of the city. Roots certainly essentially Christian, but with significant Hebrew interference.

The discovery of the mikveh is fairly recent. What have we discovered and established about its use in the Middle Ages?

Montpellier is fortunate to have, over the ages, a first-rate archaeological vestige: the mikveh, a Jewish ritual bath dating from the 12th century, known to ancient local scholars (such as Canon Charles d’Aigrefeuille in 1737), found and restored in the millennium year of the city in 1985.

Moreover, the medieval synagogal building where the Institute is based, was declared a “Historic Monument” in 2004, and is currently the subject of investigations carried out by the DRAC and the City of Montpellier with its mayor Philippe Saurel, very involved in the revaluation of the medieval Hebrew Montpellier heritage. Purpose: to try to update the medieval place of worship, the house of alms (domus helemosine) and the house of studies, components of the Schola Judeorum according to cross sources, Latin Christian and Hebrew.

By its name, this place today represents a unique place of openness and meeting. Can you meet us intercultural that marked you?

A Meeting in 2004, Rabelais room in Montpellier, entitled: “The Brotherhood of Abraham, a wishful thinking? Score for a quartet in unison?” with René-Samuel Sirat, founding president of the Maimonides Institute and former Chief Rabbi of France; Dalil Boubakeur, (then) Rector of the Great Mosque of Paris, Jean-Arnold de Clermont, (then) president of the Protestant Federation of France and Guy Thomazeau, (then) Archbishop of Montpellier.

Do you notice any changes in audience expectations compared to the pre-Covid period?

The public has returned in large numbers after the Covid-confinement period even though vigilance is still required. We now film all our events and post them on our YouTube channel. This way, people who cannot travel do not miss out on the Maimonides program.

How do you explain the great success of the Midi Libre’s special issue devoted to Occitan Judaism and is it still available online?

There is a growing interest in better understanding our common history. Montpellier and more broadly the Languedoc region were, for the medieval period, a land of passage and mixing, of Judeo-Christian encounters around the Greek-Arabic legacy. For a long time, all Jewish origins, whether familial or patrimonial, were denied. Today, without going so far as to be proud of it, there is a real curiosity about the Jewish roots of France and Europe, roots that are eminently Christian but also Hebraic. The success of the special issue can be explained in part by this.