The only remaining trace of Tarascon’s Jewish community, which was large in the Middle Ages, is rue des Juifs with its gray-fronted houses. Some of the houses have been restored. Not far from the town, near Fontvieille, there is a fine Romanesque chapel, Saint Gabriel, sheltered by a ruined tower with graffiti in Hebrew characters: T(av) T(av) Q(of) N(un) V(av) [4]956, which corresponds to the date 1195-96 C.E.

It seems that the Jewish presence in Tarascon dates from the middle of the 12th century, as Danièle Iancu-Agou mentions in her book Provincia Judaica: Dictionary of historical geography of the Jews in medieval Provence. But few documents give details of Jewish life during this period.

At the end of the 14th century and the beginning of the 15th, the documents are more numerous and precise. It seems that the Jews then lived mainly in the area between the count’s fortress and the monastery of the nuns. With the presence of a synagogue, butcher’s shop and cemetery, as well as community services. Although the homes of the Jews were officially confined to this area, the separation desired by the authorities was not fully respected by the reality of the meetings and of life. This prompted the authorities to take an official position to force the Jews to return to this neighborhood in 1418.

The 1442 cadastre lists the presence of 36 dwellings in the Jewish quarter. That of 1459 lists two more, as well as eight shops (mainly second-hand and launderers), granaries and a tannery.

The synagogue was located near the city walls and grew by a mikvah in 1442. Social works, especially helping the poor, were very active. The Jewish cemetery was located outside the Porte Condamine, as a document dating from 1426 attests.

Following the murderous demonstrations against the Jews of Arles in 1484, the situation of the Jews of Tarascon deteriorated. Some fled but were forced to return to the city to pay local taxes. Despite the subsequent expulsion and forced conversions, around ten Jews were still present in 1503, as evidenced by tax documents that taxed them. Jews who converted to Christianity were able to resettle in the 16th century. The synagogue and the cemetery were donated to Nicolas Guybert de Tarascon.

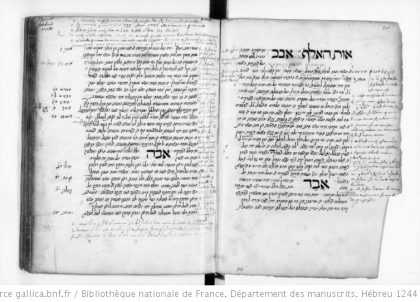

Among the Jewish personalities of the city, we can cite the mathematician Immanuel Bonfils, author of the astronomical book The Six Wings (1365), as well as Joseph Kaspi (1297-1340), philosopher and exegesis, author of Sefer Hasod.