Landlocked between Romania and Ukraine, Moldova has enjoyed a turbulent history over the past two centuries. Following the Bucharest Treaty of 1812 putting an end to the conflict between it and Constantinople, St. Petersburg annexed the eastern part of the Principality of Moldavia, under Ottoman suzerainty, and named it Bessarabia.

Bessarabia, then overwhelmingly made up of Romanian-speaking Moldovans, thus became a territory of the Russian Empire, which remained isolated from the process of creating modern Romania, consecrated in 1859 by the union of the Principalities of Wallachia and Moldova. In 1917, in the context of the collapse of the Russian Empire and the Soviet Revolution, Bucharest claimed its rights over the Romanian-speaking provinces of Bucovina and Bessarabia, which were thus attached to Greater Romania in 1918.

In 1939, following the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, the Soviet Union, which had never accepted the loss of Bessarabia, recovered this territory, which it retained until the outbreak of Operation Barbarossa and the arrival of Romanian troops in the region. In 1944, the USSR regained control of Bessarabia. The part of this region with access to the Black Sea coast is transferred to the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic, and the rest of Bessarabia becomes the Moldovan Soviet Socialist Republic, one of the 15 republics making up the Soviet Union. In 1991, Soviet Moldova gained independence and became the present Republic of Moldova. A small country of hills resolutely off the beaten track, Moldova has a rich Jewish history, that of Bessarabian Judaism, of which Meir Dizengoff, Dina Vierny and Robert Badinter are among the most illustrious children.

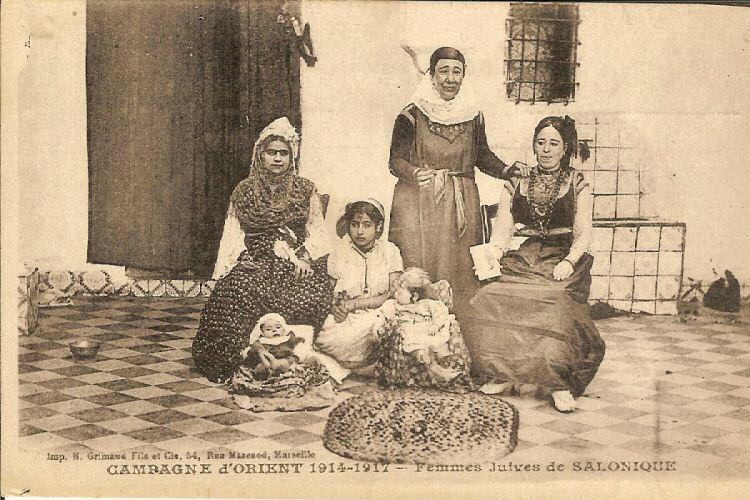

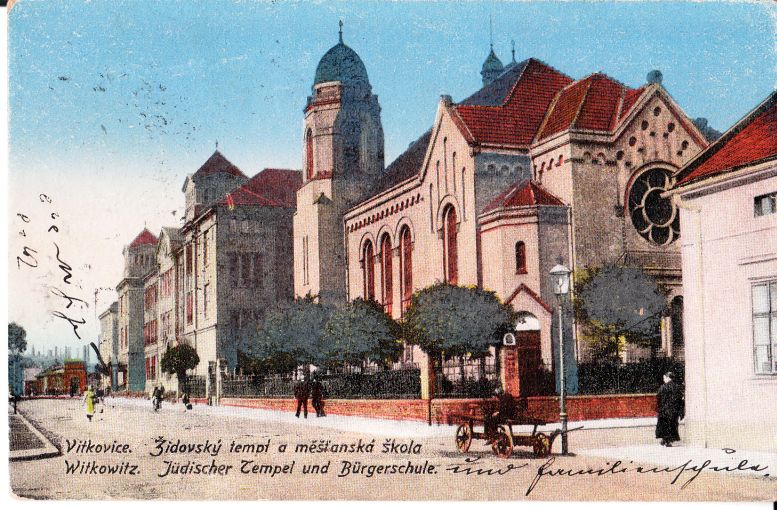

The first traces of Jewish settlement date back to the 1st century AD, when the Roman Empire conquered Dacia, a historic region corresponding to the present-day territories of Romania and Moldavia. However, it is especially from the 15th and 16th centuries that the Jewish presence will be established in a more structuring way in the region. It effectively served as a crossing point between Constantinople and the city of Lvov, then in Poland, and a number of Jewish traders from the Sublime Gate gradually set up trading posts in Bessarabia, thus developing the first communities in the region.

The Judaism of Bessarabia was marked by important developments after the annexation of this region by Russia in 1812. At that date, Bessarabia was home to a Jewish community of about 20,000 people, or about 5% of the total population, and this proportion grew very rapidly during the nineteenth century. First of all, Bessarabia is included in the “Zone of Residence”, this territory established by Catherine II in 1792 in the west of the Russian Empire and in which the Jews had citizenship. Second, St. Petersburg is pursuing a policy aimed at promoting the settlement of Bessarabia by settlers from the rest of the Russian Empire in order to promote its integration into the latter and facilitate its economic development. A number of incentives are implemented: exemption from taxes, levies, and military service for new arrivals; absence of serfdom, aid for the creation of farming communities.

In addition, Bessarabia, located on the edge of the Russian Empire, still remained in the nineteenth century, relatively untouched by the waves of anti-Semitism already hitting the empire of the Tsars. It is in this context that a certain number of Jews from other regions of the Zone of Residence settled in Bessarabia, in a more general movement of migration of Jews from northern Russia (Lithuania, Ukraine, White Russia) to the recently conquered South (in addition to Bessarabia, Odessa region, and further west of Nikolaïev and Kherson). The Jewish population of Bessarabia thus represented 80,000 people during the 1850s and then more than 230,000 at the beginning of the twentieth century, for a global population that also increased, reaching 1,500,000 in 1897. In addition to the economic attractiveness of a region to be developed, the situation of the Jews there was comparatively better than in the rest of the Russian Empire.

Until the 1840s, for example, there were no restrictions on the Jewish community in terms of land rights, the possibility of operating drinking establishments, or even settling in areas near the borders of the Empire. This explains the emergence of one of the peculiarities of Bessarabian Judaism: its strong rural dimension, evidenced by the existence of some twenty Jewish agricultural settlements in Bessarabia in the middle of the nineteenth century.

The adoption of an imperial decree in 1882 forbidding Jews from all over the Empire to exercise rural activity led to a reflux of the Jewish population of Bessarabia towards the urban centers, Akkermann, Orhei, and especially Kishinev, the capital of the province, of which more than one inhabitant in two is, at the beginning of the twentieth century, of Jewish faith. Until then living in good harmony with the other peoples of Bessarabia, Moldovans, Russians, Ukrainians, Armenians, Gypsies, Germans, the Jewish community of Bessarabia will experience the bitter experience of its first pogrom in April 1903. The Kishinev pogrom, unleashed following the discovery of the body of a young Russian boy and the false antisemitic accusations that “he had been assassinated by Jews seeking to recover his blood to prepare matzot”, caused fifty deaths and several hundred wounded. The poet Haim Bialik, commissioned by the historical commission of the Jewish community of Odessa, his hometown, to investigate the drama will draw from his visit to Kishinev a long poem, “The city of the massacre”.

The impact of Kishinev’s pogrom was considerable. A drama bringing, for the first time, international attention to the plight of the Jews in Russia. In France, Jean Jaurès will take the example of the Kishinev pogrom to criticize the policy of rapprochement with Saint Petersburg then implemented by the Combes government. The events of Kishinev also played a crucial role in the development of certain currents of the Zionist movement, in particular that structured around Vladimir Jabotinsky, whose translation into Russian of Bialik’s poem was a huge success. The Kishinev pogrom also played a major role in raising awareness among European Jewish communities of the need to defend themselves, as evidenced by the development of many Jewish defense leagues after this massacre. As early as 1904, it sparked off a major wave of departure to Eretz Israel, known in the history of Zionism as the second aliya.

With the integration of Bessarabia into Greater Romania in 1918, the Jews, like all the inhabitants of the region, became Romanian citizens but were generally considered as suspects in the eyes of the Bucharest authorities, who saw them as in the other minorities of Bessarabia, potential agents of Moscow, in any case citizens whose loyalty to their new homeland would be doubtful. This trend deteriorated with the development of state anti-Semitism in Romania during the 1930s, which reached its peak with the coming to power of Marshal Antonescu in 1940. It was from the start of Operation Barbarossa that the Shoah begins for the Jews of Bessarabia. After an initial phase – during the summer of 1941 – of extreme violence, mass executions by gunshots, drownings, and imposed famines, during which more than 100,000 people died, most of the Jews remaining in Bessarabia were herded into the ghettos of Transnistria, a region of Ukraine situated between the Dniester and Bug rivers and occupied by the Romanians until 1944 with co-religionists from Bucovina and the rest of Romania. It is estimated that around 380,000 Romanian victims of the Shoah, a majority of which lived in Bucovina and Bessarabia.

At the end of the war, this region became Soviet again, and most of the Jews who had fled it during the war resettled there. During the 1970s, the Jewish community in Soviet Moldova numbered around 100,000 people. When Soviet Jews began to be allowed to emigrate to Israel, tens of thousands of them made alya, one of the most famous being Avidgor Liebermann, born in 1958 in Chisinau. The alias of the Jews of Moldova gained momentum after independence in 1991, mainly for economic reasons.

The Jewish community in Moldova currently represents, in its broadest sense, around 10,000 people, most of them living in Chisinau. After two difficult decades, a Jewish renewal is currently at work in Moldova, structured spiritually by the Chabad community and culturally by the community center of Chisinau. In addition, a number of historic sites hitherto neglected by the authorities now appear to be receiving some renewed interest.

The Jewish presence in Cyprus probably dates from the 3rd century BC, during the Roman conquest of the island.

There seems to have been at least three synagogues, in Lapethos, Golgoi and Constantia-Galamine. The Jews took part in the revolt against Rome led by Artemion in 117 and were driven from the island by the Romans as a punishment.

The Jews settled there over time, as Benjamin de Tudela attested in the 12th century. A stabilization that continued until the advent of the Ottoman Empire.

From the end of the 19th century, following the British conquest and the rebirth of Zionism, dozens of Jewish families settled on the island. Some hoping to be able to reach Palestine then under British mandate but limiting access. In 1901, the island had 120 Jews, most of them living in Nicosia.

Following the rise of Nazism in Germany, hundreds of Jews found refuge in Cyprus. When the war ended, the island was used by England as a detention camp for more than 53,000 Jews who wished to join Israel.

They suffered from very difficult living conditions, somewhat alleviated by the help of international organizations like the Joint Distribution Committee (JDC) and the help of thousands of courageous Cypriots. Many of the prisoners had to wait there until Israel’s independence in 1948.

In 1951, only 165 Jews lived in Cyprus, a figure that fell to 25 in 1970. It took a few decades for that number to rise again significantly.

In 2005, a Chabad House opened in Larnaca, the first official Jewish place of worship for centuries. A few hundred Jews then lived in Cyprus. Arieh Zeev Raskin became its first rabbi.

Apart from the Chabad House in Larnaca, there are also four other similar places on the island. In Nicosia , Paphos , Limassol and Ayia Napa .

In 2020, this figure will be close to 3,500. Not to mention Israeli tourism, which has been on the rise for the past twenty years, with the two countries maintaining strong economic, cultural, and security ties. The country also hosts many civil marriages of Israelis, but also of Lebanese, who do not wish to depend on the religious authorities of their respective countries.

A Jewish museum is currently under construction in Larnaca to showcase the contributions of Jewish culture to the island as well as the courageous actions of Cypriots during the war to help refugees. It will also feature 19th-century Torah scrolls.

It seems that the Jewish presence on the island of Malta dates back more than 3000 years! Sailors descended from the tribes of Zevouloun and Asher accompanied Phoenician sailors. An ancient union between Jews and Phoenicians, which prospered and grew stronger over the centuries.

Traces of this link can be found in particular on the island of Gozo in the north-west of Malta, where sailors landed at the time. Similar traces are also present in the Jewish catacombs of the Greek and Roman eras. Some of the catacombs still standing today showcase Jewish symbols, including menoroth. The most famous being the catacombs of St Paul in Rabat.

Following the Arab and Norman conquests, the island’s Jews remained integrated in Malta and participated in civil society. In 1240, 25 Jewish families lived on the main island of Malta and 8 in Gozo.

During the Middle Ages, there were Jewish communities in Mdina, Birgu, Valletta and Zejtun. Thus, we find in Mdina a “Jewish silk market”, in Birgu a Jewish street and in Zejtun a Judaic place. There are also “Gates of the Jews” in several cities, the only places where Jews were allowed to enter the city.

Among the figures of the period was the mystical author Avraham Abulafia who resided in Comino between 1285 and his death a few years later. There he wrote his “Sefer ha Ot” and “Imrei Shefer”.

The Jews came mainly from Sardinia, Sicily, Spain and North Africa. And their living conditions were relatively less difficult than in most Mediterranean regions at the time. Sometimes occupying prestigious positions such as that of chief physician. Position held in particular by two members of the Safaradi family, Bracone and Abraham.

The Jewish population increased under Spanish rule. At the beginning of the 15th century, the Bishop of Malta as well as civil authorities removed discrimination against Jews. Xilorun, a Jew from Gozo was even appointed Ambassador of Malta to Sicily. However, the Inquisition of 1492 led to the confiscation of their property and their expulsion. Some fled, and others were converted. Many Maltese are still found today with surnames of Jewish origin.

During the reign of the Knights of the Order of St. John, which lasted until the defeat by France in 1798, the population was subjected to martial politics. Without distinction, all kinds of populations found themselves victims of military raids on sea and land, liable to be captured and enslaved. This was particularly the case with the Jews, who were also obliged to wear distinctive signs. There are many accounts of the looting, murder, and sale of slaves during these centuries.

On the road to Egypt, Napoleon conquered Malta in 1798 and therefore applied French law there, including the abolition of slavery and equality between all citizens. This acquired freedom was maintained by the British conquerors soon after. In 1846, the community had its first official rabbi since the time of the Inquisition: Josef Tajar.

During World War II, Jews fleeing Nazism did not have to have a visa to arrive in Malta, which allowed thousands of them to seek refuge there. Many Maltese Jews enlisted in the British Army at the time.

The country gained its independence in 1964. Following neighborhood renovation projects, the old synagogue in Malta was destroyed in 1979. In 2013, a Chabad House was also established on the island.

The very small and ancient Maltese Jewish community is composed of 200 persons in 2025. Most Malta Jews live in Valletta.

There are three Jewish cemeteries in Malta. The oldest cemetery in Kalkara dates from the 18th century. In the suburbs of Marsa is the second, which dates from the mid-20th century. The third is located in Tal Braxia and is abandoned.

The Jewish presence in Gibraltar seems to date back to the 14th century. A historical document from 1356 refers to an attempt by the Jewish community to free prisoners held by pirates.

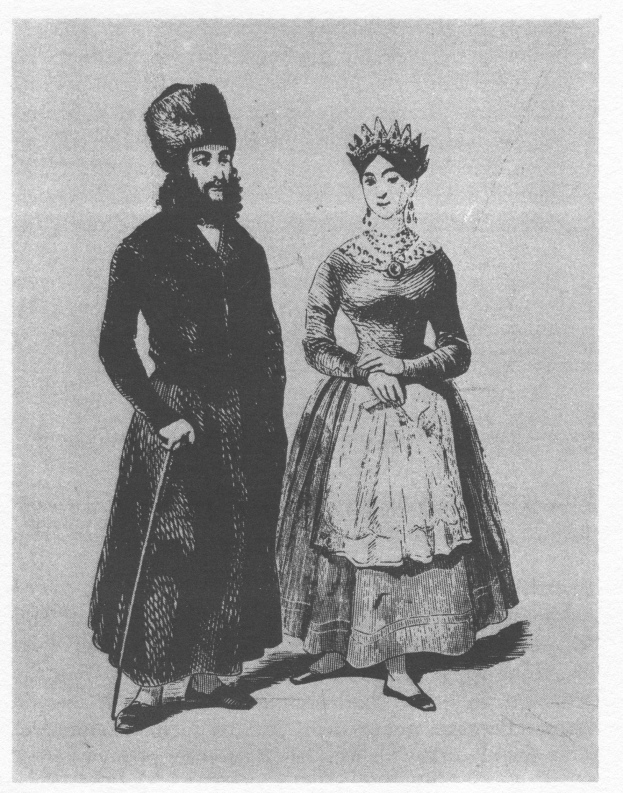

During the Inquisition of 1492, many Jews fled to North Africa via Gibraltar. When, following the Treaty of Utrecht of 1713, the island came under British rule, Jews were allowed to settle there. During the 18th century, Jews settled in Gibraltar, notably merchants from Tetouan in Morocco, later joined by English and Dutch.

In 1805, they constituted half of the inhabitants of Gibraltar, even creating a newspaper in Ladino, “Cronica Israelitica”. In 1878, the island had more than 1,500 Jews.

In the 20th century, this figure declined rapidly until the beginning of the next century, notably following the evacuation of civilian populations during World War II and the Franco blockade.

An increase in the Jewish population was seen at the start of the 21st century. There are believed to be just under 800 members of the Jewish community in Gibraltar today, constituting 2% of the population.

There are four synagogues in Gibraltar.

David Nieto, Chief Sephardic Rabbi in England, had Isaac Nieto as a son. He was appointed rabbi at the English synagogue at Bevis Marks. He then headed the Shaar Hashamayim Synagogue , built in the mid-18th century, which was also inspired by the architecture of Bevis Marks. It is still Gibraltar’s main synagogue today.

The Etz Chayim Synagogue was inaugurated in 1759 on the premises of the former yeshiva founded by Isaac Nieto. Following the Moroccan rite, it was destroyed and later rebuilt.

The Nefutsot Yehuda Synagogue was founded by Dutch merchants in 1800. Built in a garden, it is architecturally inspired by the Sephardic synagogue in Amsterdam. Destroyed by fire in 1913, its style changed during its reconstruction, more inspired by an Italian touch inside the walls.

Following the death of Rabbi Solomon Abudarham in 1804, his Talmudic school was converted into a synagogue fifteen years later. The Abudarham Synagogue is a small place of worship with wooden PEWS facing the bimah.

The Jews Gate Cemetery , the ancient Jewish cemetery, is located on Windmill Hill. It was used between 1746 and 1848. This is where the former Grand Rabbis of the island were buried. The cemetery is located near the Pillars of Hercules monument.

The current cemetery is on Devil’s Tower Road. Heroes of the First World War and the Second World War are buried there.

While Jews have lived in Albania for centuries, there is little physical evidence of their presence in Berat, Sarande, Tirana and Vlore. A good reason to visit Albania, however, might be to pay homage to besa, the Albanian code of honor and hospitality. Through this practice, Muslims and Christians risked their lives during World War II to save the local Jewish population, as well as hundreds of refugees from neighboring countries.

The Jews of the Balkans were linked by family and business ties. Thus, Albanian Jews were particularly close to the communities of Corfu and Ioannina.

According to Albanian historian Apostol Kotani, Jews arrived in Albania around AD 70. Sources mention Roman ships with Jewish prisoners on board who were reportedly stranded in Albania after their ships sank. The descendants of these captives may have been those who built a synagogue in the southern port city of Sarande in the 5th century.

Other accounts point to a small group of Jewish merchants living in the city of Durres, an important point on the trade route between Rome and Istanbul.

Development of the Jewish communities of Albania

In the 15th and 16th centuries, the Jewish community represented a third of the population of Vlore, then the administrative and commercial capital of the country. The Jews of Vlore came from France, Corfu, Spain, and even Naples. They exported textiles and leather.

In the 17th century, Vlore lost its importance to Berat where followers of Sabbatai Zeevi settled.

Finally, in the 19th century, a large community from Greece settled in Albania. The same phenomenon recurred after the country became a monarchy in 1928. The census of 1930 mentions 204 Jews.

Note that in 1935, the country’s tolerance and tranquility made it a potential candidate for the establishment of a Jewish home.

Hiding Jews during the Holocaust

After Hitler came to power, Jews from Germany, Austria, Czechoslovakia, and even Poland found refuge in Albania. The Albanian Embassy in Berlin issued visas to all Jews who requested them, when no country dared to do so – remember that Albert Einstein fled Germany in 1935 with Albanian papers. Thus began a remarkable rescue, both at the state level – on the orders of King Zog – who refused to give the German authorities his census lists; than at the level of its predominantly Muslim population who hid the Jewish community at the risk of its life. Only one family was deported. Albania therefore not only rescued 200 local Jews, but also 2,000 foreign Jewish refugees. Albania is thus the only country to have increased its Jewish population tenfold between 1939 and 1945. To date, 69 Albanians have been elevated to the rank of Righteous Among the Nations.

To learn more about this little-known aspect of WWII, it is recommended to watch the American documentary Besa the Promise so you will find the trailer here in English.

After the end of the war, 180 Jews lived in Albania. When the borders opened in 1991, the majority left the country for Israel. There are in 2021 from 50 to 200 Albanian Jews.

The first documents attesting to the presence of Jews in Luxembourg date from 1276, when an act mentions the Jewish religion of Henri de Luxembourg. The Jews have lived in the Pétrusse valley at the time.

Persecutions, leading in some cases to death, followed charges of poisoning wells during the plague epidemic of 1348. The Jews who survived these persecutions fled the country, from which they were officially expelled in 1391. Some families tried to stay in Luxembourg and Echternach, but, in 1532, the Edict of Charles V put an end to these hopes.

In the emancipatory spirit of the French Revolution, Luxembourg, conquered by France, applied imperial directives. Thus, on July 14, 1795, the discriminatory taxes imposed on the Jews and the geographic limitations were abolished by decree.

An early 19th century census shows that 75 Jews live in Luxembourg. A fairly young age average. They mainly came from villages of the Moselle and the Saar. People attracted by the hope of being able to work trade or crafts and live their religion freely.

Two characters symbolized the roots of the Jews on Luxembourg territory. First, Jean Baptiste Lacoste (1753 – 1821), lawyer and former deputy of Cantal to the Convention. He was appointed prefect in Luxembourg and in the company of the Municipal Council and the Imperial Prosecutor, they attested to the Court of First Instance that “civil and political conduct was free from all reproach and that police surveillance encountered no complaint. particular against them, which is a constant testimony of their morality ”.

The other outstanding figure was Pinhas Godchaux. Born in 1771, and coming from a Messina family and having among his ancestors the Maharal of Prague, Pinhas Godchaux moved to Luxembourg in 1798. Gradually, he became the leader of the Jewish community, first attached to the Consistory of Trier then to the one of Maastricht.

From 1815, the Jews, coming mainly from Germany and Lorraine, settled successively in other cities: Arlon (city which was part of Luxembourg until 1839), Ettelbruck, Grevenmacher, Mertert, Dalheim, Echternach, Grosbous, Erpeldange, Frisange, Schengen and Esch.

The inauguration of the first synagogue in Luxembourg took place in 1823, in the rue du Petit Séminaire. Following the arrival of other Jewish families the regions of Alsace and Lorraine during the War of 1870, the community obtained the right to build a second synagogue, inaugurated on September 28, 1894 by Rabbi Isaac Blumenstein and the President of the Consistory Louis Godchaux welcoming on this day the high Luxembourg authorities. During this century, the towns of Ettelbruck, Mondorf and Esch also built a synagogue.

Clausen Malakoff , created in 1817, was the first Luxembourgish Jewish cemetery. It remained active until 1884, when the Bellevue cemetery was used instead. Ettelbruck (1881), Grevenmacher (1900) and Esch-sur-Alzette (1905) also allowed the creation of Jewish cemeteries.

Rabbi Samuel Hirsch was the great intellectual Jewish figure of that time. Trained in the eminent traditional community of Dessau, his liberal vision of Judaism, promoting the familiarity of the Jewish philosophical approach and contemporary societal thought, forced him to leave the institution. Although he was appointed Chief Rabbi of Luxembourg from 1843 to 1866, he failed to convince the traditionalist community of his reformist approach. He then shared it in Philadelphia, deeply inspiring the American liberal current.

At that time, Samson and Guetschlick Godchaux, the nephews of Pinhas, revolutionized the weaving trade and the condition of workers in the 19th century. An economic adventure that started in 1823 with two weaving looms in a shed on rue Philippe II. Moving to Schleifmuhl, the company developed its activity. Associated at the end of the century with the manufacturer Conrot, the family employed more than 2,000 workers, the majority of whom were in Schleifmuhl. The evolution of social condition is characterized by the construction of a workers’ village with small houses in Hamm. Far from being a dormitory town, this village had its own choir, a nursery and a nursery school as well as a Kayak club. It organized cultural events and above all a society of mutual aid, a kind of early social security experiment. The decline started after World War I. The factories closed in 1939. Emile Godchaux, descendant of the family and last director of the company, was deported at Theresienstadt and died there in 1942.

In the interwar period, many Jews from Eastern Europe fleeing poverty and anti-Semitism settled in the Grand Duchy, encouraged by the invitations to tender in the mining basins of the steel industry. This immigration continued with the arrival of Jews from Germany and Austria between 1935 and 1940, following the application of the Nuremberg laws.

On May 10, 1940, Luxembourg was invaded by the German army. Its 4,000 Jews were persecuted by the Nazi chief of civil administration sent by Berlin. The synagogues of Luxembourg and Esch were destroyed.

A period also marked by the courage of a handful of men who managed to organize the escape of the Jews from Luxembourg. Chief Rabbi Serebrenik was assisted by a Wehrmacht officer in charge of the passport office, Franz von Hoiningen Huene (François Heisbourg recounts this period in the book “This strange Nazi who saved my father”), the American charge d’affaires George Platt Waller and by the former president of the Consistory, Albert Nussbaum.

The latter organized a complex network from Lisbon, funded by the American organization JDC. The JDC enabled many Luxembourgish, but also Belgian, German and Eastern European Jews to embark for the United States, Brazil and other Latin American destinations such as Cuba, Jamaica or Venezuela.

Victor Bodson, former Minister of Justice, saved Jews by helping them to flee the country. In particular by the Sauer river near where he lived and which marks the border between Germany and Luxembourg. For his courage, he was then named Righteous among the Nations.

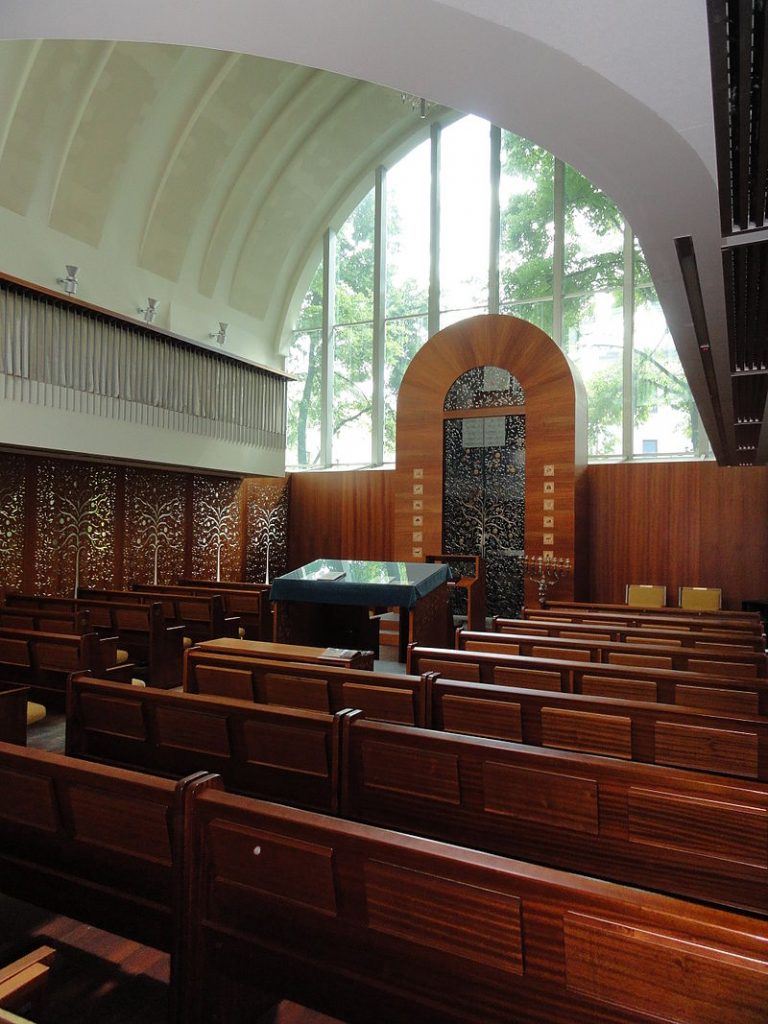

Following the Liberation on September 9, 1944, the 1,500 Luxembourg Jews who survived rebuilt the community, thanks in particular to government assistance. Architects Victor Engels and René Maillet constructed a building that serves as both a place of worship and a community center.

The inauguration took place on June 28, 1953, in the presence of HRH the Grand Duke Jean, the high authorities of the City and the State and numerous rabbis among whom the Chief Rabbi of France Jacob Kaplan. Chief Rabbi Lehrmann consecrated the synagogue during a solemn ceremony presided over by the President of the Consistory, Edmond Marx.

A year later, Esch-sur-Alzette also hosts a synagogue . Of liberal current since 2008, it is located on the rue du Canal. A building made in the same style as the city synagogue built in 1899 and destroyed during the war. We particularly notice its large stained glass windows. The Esch synagogue celebrated its 70 years in 2024.

One can also visit the ancient synagogue of Mondorf-les-Bains which is today a cultural center. The Ettelbruck synagogue, ceded by the Luxembourg Consistory to the city of Ettelbruck which has made it a Culture and Meeting Center will soon house a Museum of Luxembourg Judaism.

Doctor Emmanuel Bulz greatly marked the contemporary period of Luxembourgish Judaism. Chief Rabbi from 1958 to 1990, he worked constantly for a rapprochement with the non-Jewish world and more particularly Luxembourg civil society. This, by sharing a knowledge of Judaism and a demythification of certain prejudices. Joseph Sayag succeeded him, then Alain Nacache, Chief Rabbi since 2011.

The work of historians such as Serge Hoffmann, Paul Dostert and Denis Scuto, as well as the political action of deputy Ben Fayot allowed a precise study of the history of the Luxembourg Jews during the Shoah. This resulted on February 10, 2015, in the presentation by Vincent Artuso of his report “The Jewish Question in Luxembourg, 1933-1941. The Luxembourg State faced with anti-Semitic Nazi persecution”.

On May 11, 2015, the decision was made to erect a monument to commemorate the victims of the Holocaust. A monument inaugurated on June 17, 2018 in the presence of the Grand Duke Henri, the Grand Duchess Maria Teresa and the national and municipal political authorities. The monument is located in the heart of the city. A memorial carved in pink granite by the artist and survivor Shelomo Selinger, close to the Gëlle Fra, symbol of the freedom and resistance of the Luxembourg people.

The Luxembourg Foundation for the Memory of the Shoah (FLMS) was created in 2018. A structure whose mission is to perpetuate the memory of the Shoah but also of all other crimes against Humanity. It also fights preventively by organizing programs against racism, revisionism and negationism. Historical revenge, since the site is located on the site of the former Gestapo headquarters.

Another interesting place to visit is the National Resistance Museum located in Esch. He retraces this history in Luxembourg during the war. Photos, objects and works of art are presented to the public. Renovations were carried out between 2018 and 2023. Since 2024, it has had a much larger surface area.

Interview of Claude Marx, former president of the Israelite Consistory of Luxembourg

Jguideeurope: The Memoshoah Association devoted an exhibition to the rescue of Luxembourg Jews to Portugal and the Atlantic crossing. How was this rescue organized logistically?

Claude Marx: On May 10, 1940, during the invasion of the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg by the German army, the Jewish community was made up of 1,000 Luxembourgers and around 3,000 foreign Jews, mainly German and Austrian refugees. 45,000 people are fleeing the country, of which around 1,500 belong to the Jewish community. Many of these German, Austrian and stateless immigrants who have been unable to flee are going to great lengths to seek lighter skies.

An evacuation project was imagined in July by the association of several people: Chief Rabbi Robert Serebrenik, Albert Nussbaum, a Jewish merchant and President of the Consistory and Baron Franz von Hoiningen Huene, a German officer, notorious anti-Nazi and responsible from the passport office, could be finalized on August 8, 1940.

Between August and October, real and false visas bought very expensive by the Consistory allow, thanks to passes issued by von Hoiningen, several hundred refugees to cross France, then Spain, and finally succeed in Portugal from where they will have the possibility of embarking towards South America, the Dominican Republic or the United States.

A convoy that left on November 7, 1940 with 293 Jews was arrested in Vilar Formoso, a border town between Spain and Portugal, after the Portuguese border guards discovered on board uniformed and armed SS men. The convoy had to turn back to France after 10 days, stopped on a siding with a ban on passengers getting off.

Despite this incident, 7 other convoys were still organized, allowing several hundred refugees to escape death. On May 20, 1941, Chief Rabbi Serebrenik was informed by von Hoiningen that he was designated “for liquidation” as he soberly stated in his memorandum. On May 26, 1941, he accompanied a convoy bound for Lisbon and was able to embark for New York. On October 15, 1941, a last convoy of 132 people left Luxembourg. It was about time: on November 16, 1941, the first German transport to the East took 323 Jews deported to Litzmannstadt.

Do you think that there has been an important evolution in Luxembourg in the approach to the history of the Jews?

It was only after the conquest and annexation by France in 1795 of the Duchy, which then became the forest department, that the new legislation granting citizenship to the Jews allowed a few families to settle in the Luxembourg. A character from Lorraine, Pinhas Godchaux, intelligent and cultured, has the confidence, esteem and consideration of both the authorities and the Jewish community. His charisma and relationships will allow a rapid improvement in the economic conditions of the Jewish Community. As for the observations made on the morality of people, they are particularly flattering (“lives off his business as an honest man”, “deserves public confidence”, etc.). Chief Rabbi of Luxembourg in the 19th century, Samuel Hirsch, promoter of a line of radical reform of Judaism and who belongs to a Luxembourg masonic lodge, inaugurates a new period which will allow certain intellectuals, industrialists and financiers to tie through the masonry, constructive links across Europe. At the same time, the Godchaux family will build in Luxembourg an industrial empire inaugurating social laws favorable to the workers, which will considerably promote the attitude of Luxembourg society towards the Jews.

The successive rabbis after the war contributed significantly to the good relations between Luxembourg Civil Society and the Jewish Community. It is necessary to quote more particularly Charles Lehrmann, doctor in philosophy and licensees-es letters, convinced of the need to make known to his non-Jewish contemporaries what is Judaism, and who allowed by his radio talks to bring another look at the Jewish Community. From 1958, it was the Chief Rabbi Emmanuel Bulz who assumed the pastoral charge at the head of the Jewish Community of Luxembourg. Prodigiously cultivated, a great resistance during the war, Emmanuel Bulz concentrated his efforts on the Judeo-Christian dialogue. His speeches, lectures and radio broadcasts on a wide variety of subjects have earned him the respect and admiration of large sections of the Luxembourg population. Dr. Bulz’s commitment to a greater fraternity, his work for inter-religious dialogue are still very much present in Luxembourg’s memory and reflect on the Jewish community.

How was the decision made to rebuild the synagogues of Luxembourg and Esch?

In the aftermath of the Second World War, the Jewish Community of Luxembourg was devastated: a third of its population on May 10, 1940 disappeared in the storm. For those who, hidden somewhere in Europe have survived, for others who have emigrated across the seas and who return to the country, the essential concern, in a country devastated by war where the accounts between patriots and collaborators of the Nazi regime, is to rebuild a family and professional life, to find its marks. The synagogues of Luxembourg and Esch having been destroyed by the Nazis, a Consistory quickly constituted with at its head Mr. Edmond Marx, Vice-President of the Pre-War Consistory, set to work to find a Religious Center. The state is ready to help, but in view of the destruction, it is urgent and the religious project is not a priority. Negotiations for a new location, plans and funding will take 8 years. During this transitional period, a room for worship was rented in the Stock Exchange building. The synagogue, resolutely modern and designed to also serve as an Administrative Center, was inaugurated on June 28, 1953.

In Esch sur Alzette, it is also in a very modern style, adorned with superb stained glass, that with the financial aid of the State, the commune and the Office for war damages, the rebuilt synagogue was inaugurated on October 17, 1954.

Can you tell us about your project concerning Jewish cultural heritage in association with the Luxembourg Ministry of Culture in the UNESCO zone?

Since 1994, the fortress of the City of Luxembourg and its old districts have been part of the cultural heritage of UNESCO. In collaboration with the Israel Consistory, a Jewish heritage itinerary project should soon highlight the historical past of the Jewish community, talk about Jewish businesses, and the social impact of that community. The aim of the walk will be to show that the history of the Jewish community is an integral part of that of the country and an important part of UNESCO’s world heritage. The visits are intended to recall to what extent the Jewish presence represents a cultural and entrepreneurial enrichment for society.

Famous personalities from the Jewish Community, shops, monuments, commemorative places will be evoked during this guided tour by the Izi travel app in French, German, Dutch, English and Luxembourgish. One of the highlights of the visit will be the “Kaddish” monument, created by French-Israeli artist Shelomo Selinger.

Straddling Europe and Asia, Georgia, situated between the eastern shores of the Black Sea and the high mountains of the Caucasus, is a land of plenty, rich in exceptional nature and in historical heritage. Well preserved, it was praised by Pushkin, Alexander Dumas, or Lermontov.

The Georgian nation, whose genesis goes back to the kingdom of Colchis, is evoked in the myths of the Golden Fleece and Prometheus. In the fourth century, it takes for religion Christianity, like neighboring Armenia. Federated in the eleventh century under the reign of King Bagrat III of Abkhazia, the kingdom of Georgia then enters a long period of instability as much related to the internal divisions as the pressures of the Byzantine and Mongolian, Arab, Persian and Ottoman neighbors and invaders.

Annexed to Persia by the Russian Empire at the beginning of the nineteenth century, in the context of the advance of St Petersburg in the Caucasus, the Republic of Georgia will experience an ephemeral independence between 1918-1921, before being integrated to the Soviet Union, like the other two countries of the South Caucasus.

Tbilisi regained its independence in 1990. After a particularly dark 1990s, notably marked by the civil war, Georgia has been engaged since the beginning of the 2000s in a dynamic of international openness and modernization, becoming one of the most welcoming country in the region.

The history of Georgian Jews is at least as old as the history of Georgia itself. Their presence in the area echoes several biblical stories. According to the first, the Georgian Jews would be ancestors of the 10 lost tribes of Israel, exiled from Jerusalem to other areas of Assyria by King Salmanasar around the eighth century BC.

According to the second version, they are descendants of the inhabitants of the kingdom of Judah, exiled by Nebuchadnezzar II after the capture of Jerusalem in 597. This version also explain why the Georgian Jews are called “guriyim”, which means lion cub in Hebrew, the emblem of the tribe of Judas.

Finally, the region of the Caucasus, and in particular the territory of present-day Georgia, would also have welcomed Jewish populations exiled from Jerusalem after the second destruction of the Temple by the Romans in 70. Parallel to the biblical stories, the presence of Jews in the territory of present-day Georgia is mentioned in the first History of Armenia, written by Moise of Khorene around the fifth century of note era. According to the historian, several kings of Georgia and Armenia, including those from the Bagrat family, were of Jewish origin, would descend from King David. For their part, the Georgian Chronicles, written between the ninth and the fourteenth century, relate that the people of Georgia would already bring the people of Israel when Moses crossed the Red Sea.

Developing over the centuries their own dialect, kivrouli, Georgian Jews are mainly engaged in agricultural activities, which explains in particular the presence of settlements throughout the territory, and not only in large urban centers.The history of Judaism in Georgia knows an important turning point in the early nineteenth century, when under the terms of the Golestan Treaty, signed in 1813 between St. Petersburg and Tehran, Georgia is integrated into the Russian Empire.Along with the Mizrahim Jews, indigenous, a number of Ashkenazi from other parts of the Russian Empire will gradually settle in Georgia: this region of the Russian Empire has about 20,000 Jews in the 1860s. This is why, even today, a distinction is made between the synagogues of Georgian rite and those of Ashkenazi rite. It is the rise of the Zionist movement in Russia that will allow, at the end of the nineteenth century, the development of contacts, hitherto limited, between the two communities. Georgia became part of the nascent Soviet Union in 1921, and like the rest of the USSR, Jewish citizens enjoyed a certain freedom of worship there until the turn of the 1930s, from which a major repression in the religious sphere is started. It should be noted that for a variety of reasons this repression was less noticeable in Georgia, where Jews were able to maintain a number of religious activities.

On the whole less assimilated than most other Jews of the Soviet Union, Georgian Jews benefited in priority of authorizations to emigrate to Israel: their alyah begins in the early 1970s, after a group of Georgian Jews sent, in 1969, a request for assistance to the United Nations, which then had international repercussions.This emigration is particularly the subject of a cult scene of the Soviet film Georgian Mimino (1977), where the main character seeks to call in the Georgian city of Telavi, but is put, following a mistake by the operator, in relation with Tel Aviv. By chance, a Georgian Jew answers him. It follows a long dialogue interspersed with traditional Georgian songs between the two characters. This scene will remain for a long time the only evocation, on a comic note, of the emigration of the Soviet Jews in Israel.

Today, the Jewish community in Georgia, which numbers about 5,000 people, is concentrated mainly in Tbilisi, Kutaisi, and Batumi on the shores of the Black Sea. Dynamic, this community also benefits from Georgia’s success with Israeli tourists, whose growing influx, about 60,000 per year, has contributed for several years to a real revival of local Jewish life.

Until the end of the Middle Ages there were no Jews in Norway, which was ruled by Denmark until 1814. It was not until the beginning of the 19th century that they settled very tentatively, especially Sephardic Jews.

Henrik Wergeland (1808-1845), a pastor’s son and theology student, was known for his poetry and his political commitment to human rights, an expression he used regularly a hundred years before the United Nations Charter. Among his concerns was the fate of the Jews, excluded from the Kingdom of Norway since 1814. He addressed parliament four times to have this ban lifted. He also fought this battle in his poetry, describing the Jews and their culture. In 1851, six years after Wergeland’s death, two-thirds of parliament voted to end the ban. In 2003 a large exhibition was dedicated to him.

Following the decision of the Norwegian Parliament, Jews timidly settled in the country, most of them coming from Germany. At the end of the 19th century, it was the case of Jews from Eastern Europe, fleeing pogroms, mainly from Russia, Poland and the Baltic States. The very difficult living conditions at that time motivated the departure of many Norwegians and Jewish refugees who were in transit to the United States. It is estimated that 800,000 Norwegians migrated to America between the 1880s and 1920s, for a country with a population of just over 2 million.

A large proportion of Norwegian Jews worked as merchants or craftsmen, accompanying the economic development of the country. As their integration progressed, the Jews were able to diversify their professions, especially in medicine and culture, like the violinist Jacques Maliniak (1883-1943). They lived mainly in Oslo and Trondheim, but also in sixty-two other municipalities, in very small numbers in these cases. Thus, there were only 25 Norwegian Jews in 1866, 214 in 1890 and 642 at the turn of the century.

On the eve of the Second World War, the Jews were fully integrated into society, adopting Norwegian as their first language and living on Norwegian time. They participated in all sectors in economic and cultural circles. Quisling’s Nazi party, in the pay of the German occupiers, soon began a campaign of denigration of the Jews and confiscation of their property. Files, prepared even before the outbreak of the war made it possible to identify the places where the Jews lived.

On 6 October 1942 the first mass arrests of Norwegian Jews began in Trondheim. They tried to oppose these acts, including Moritz Rabinowitz, a philanthropist and educator of the working class who was murdered, along with his family. The courage of Norwegian resistance fighters saved many Jews, helping them to flee the country across the Swedish border. During the Holocaust, more than a third of the 2,200 Norwegian Jews were deported. Only 29 survived.

In the aftermath of the war, Norwegian Jews founded a new community. Among these survivors was Kai Feinberg, who also told in his autobiography how painful it was for him, the only survivor of his family, to return “home” and find that the homes of the Jews had been given to other families.

Following articles about the spoliations in 1995, the Norwegian authorities studied the issue and in 1999 voted for compensation for Norwegian Jews, one of the first European countries to resolve this injustice.

Today, Norwegian Jews number less than 2,000 in the whole country, mainly in Oslo and Trondheim. Since 2009, Jews have been the target of a resurgence of antisemitism wearing different masks, as in many other European countries.

The Norwegian community can pride itself on having given Israel a minister: the great rabbi Michael Melchior, who became a deputy in 1999 and later a member of the Barak government in charge of relations with Diaspora Jews.

Although strictly Orthodox, Rabbi Melchior (son of the former grand rabbi of Denmark, Bent Melchior) belongs to the center-left party Meimad.

Sources : Jewish Life and Culture in Norway : Wergeland’s Legacy, Encyclopaedia Judaica, Times of Israel

There are nearly 15,000 Swedish Jews today. Most live in Stockholm. The other communities are mainly located in Malmo, Goteborg, Lund, Helsingborg, Boras and Uppsala.

Synagogues are present in the first three cities of the country. And Jewish cemeteries in Gotand, Kalmar, Karlkrona, Karlstad, Larbro, Norrkoping and Sundsvall.

Although the presence of Jews in Sweden dates back a long time, notably in Goteborg and Stockholm, a community was not established there until the 1770s. Aaron Isaacs, a German engraver living in Stockholm, was the first Jew to live there. be allowed to live there as such at that time, without having to convert to Christianity.

The island of Marstrand, located near Goteborg, allowed the arrival of populations of other countries or other religions. In this momentum, the city of Goteborg authorized the settlement of Jews in 1782. The other towns that authorized their visit were Norrkoping and Karlskorna. In that same year permission was granted to build synagogues in these cities.

In 1840, the number of Swedish Jews was estimated at 900. At that time, King Charles XIV granted many civil rights to Jews. Once this access to citizenship and equal rights was granted, Jews rarely encountered anti-Semitism.

This development motivated the arrival of Jews from neighboring countries, more worried about their fate, notably from Russia and Poland. Thus, the Jewish population of Sweden increased to reach 6,500 in 1920.

In the interwar period, more restrictive measures were implemented to limit Jewish immigration. From 1933 to the start of the war, only 3,000 Jews were allowed to settle there, mainly from Germany, Austria, and then Czechoslovakia, the places conquered by the Nazi regime.

Nevertheless, during World War II, many Swedes were involved in rescuing the Jews. In 1942, 900 Norwegian Jews were granted permission to settle in Sweden. And of course the two famous rescue operations.

First of all, that of the 8,000 Danish Jews who found refuge there thanks to the courage of the people of their country. Then, the valiant efforts led by the Swedish diplomat Raoul Wallenberg made it possible to save thousands of Hungarian Jews. It should be mentioned, however, that some Swedish companies adopted a different attitude and traded with Germany.

The Jewish community developed after the war, in particular thanks to the arrival of Jews from communist countries, mainly from Poland and Czechoslovakia.

But by the end of the 1980s, neo-Nazi and Islamist speeches and attacks against Jews spread. This encouraged Swedish political institutions to set up educational projects to combat anti-Semitic and racist prejudices. Particularly thanks to the University of Uppsala.

This did not prevent the rise of anti-Semitic attacks across the country, which rose sharply in the 2010s. Whether it was the Molotov cocktail attack by Islamists on the Stockholm synagogue.

A year later, it was the home of a Jewish politician from Lund that was burned down. Hence Prime Minister Stefan Lofven’s decision to add more educational programs but also to increase the penalties for anti-Semitism.

In 2017, during an Islamist demonstration in Helsingborg, violent anti-Semitic slogans were uttered under the guise of “anti-Zionism”. In Umea, a Jewish cultural center was closed in 2017 following the vandalism suffered at its premises and the many threats received. In Norrkoping, during the Passover celebrations in 2021, bloody dolls were hung on the synagogue …

Finland was part of the Kingdom of Sweden until 1809. Thus, during Swedish rule, Jews were allowed to live in only three cities, none of which was on the territory of Finland. Following the war between Sweden and Russia, Finland came under Russian control, but the legal system in force remains that put in place by Sweden. The Jews were therefore not allowed to settle there.

The first Finnish Jews settled in two different ways. The first migrants were from Sweden, singers who were allowed to perform there in 1782 to share their art. Finland was then part of the Kingdom of Sweden, and Jews were previously only allowed to settle in Stockholm, Gothenburg and Norrkoping. Jakob Weikam was the first Jew to settle officially in Finland, in the town of Hamina, in 1799. Others gradually settled in Finland as the migration laws changed.

Nevertheless, the majority of Finnish Jews were descendants of Russian soldiers who had settled in the region. Regulations restricting or prohibiting the settlement of Jews in Finland did not apply to Russian soldiers. The long period of military service also encouraged settlement once the return to civilian life was determined.

The law evolved slowly. In 1889, the government in place authorized by decree the presence of Jews in Finland. This decree did not guarantee a long-term presence and confined the Jews to certain regions and professions. Professional activities are also geographically limited, prohibited from markets and forced to be near the place of residence.

Although debates on the emancipation of Jews and their access to equal citizenship status have been public since the 1870s, access to these so-called rights did not materialize until 1917. When Finland finally achieved independence. Parliament promulgated a law in 1918 allowing Jews to acquire Finnish citizenship.

The country’s Jewish population grew from a thousand at the end of the 19th century to two thousand in the interwar period. Mainly as a result of the emigration of Russian Jews at the start of the Bolshevik Revolution, but also Polish and Lithuanian Jews. Most Jews then worked in the textile industry, following a tradition of attachment to one of the few permitted professions in the 19th century.

The fate of Finnish Jews during World War II was somewhat paradoxical. Finland’s involvement in the Second World War began during the Winter War (30 November 1939 – 13 March 1940), when the Soviet Union invaded Finland. Finnish Jews evacuated from Finnish Karelia along with the other inhabitants. The synagogue in Vyborg was destroyed by aerial bombardment in the early days of the war. 327 Finnish Jews fought for Finland during the war.

Many Jews enlisted in their country’s army against the Russians, sometimes finding themselves in close proximity to the German army, which was allied with Finland. With a famous anecdote from the Russian Front, worthy of the great moments of Jewish humor close to the spirit of a Romain Gary in his novel Genghis Cohn, where the Jewish soldiers had set up a prayer tent a few steps from the Reich army.

In November 1942, eight Austrian Jewish refugees (along with 19 others) were deported to Nazi Germany after the Finnish police chief agreed to hand them over. When the Finnish media reported the news, it caused a national scandal and ministers resigned in protest. After protests from Lutheran ministers, an archbishop and the Social Democratic Party, no more foreign Jewish refugees were expelled from Finland.

Around 500 Jewish refugees arrived in Finland during the Second World War, but around 350 left for other countries

Marshal Mannerheim, then President of Finland, attended the memorial service for fallen Finnish Jews at the Helsinki synagogue on 6 December 1944.

On the other hand, an investigation conducted in 2018-2019 clarified the involvement of Finnish volunteers in the Waffen SS, and their part in the perpetration of violence against Ukrainian civilians, many of them Jews. On their return, these volunteers kept discreet, trying to forget their involvement, which complicated the research.

Following an arrangement between the Russian and Israeli authorities in the 1980s, 20,000 Jews were able to make alya through Finland, most of them being welcomed and helped by volunteers from the Zionist Christian movement in Finland.

Historically, anti-Semitic hate crimes have been rare and the Jewish community has been relatively safe, but a few anti-Semitic crimes have been reported in the last decade. A Jewish MP in parliament, victim of insults and swastika on posters.

The few dozen members of the liberal movement have no place of worship and are attached to the liberal community of Copenhagen.

Yiddish was enjoying a revival in Helsinki, thanks in particular to Limud’s international meetings.

In 2025, Finland’s Jewish community represents around 1,500 people. Most live in Helsinki. However, 200 live in Turku and around 50 in Tampere.

Of the approximately 8,000 Jews living in the country of Denmark, the great majority of them as Ashkenazim who make Copenhagen their home. In 1968, 2500 Polish Jews fled the anti-Semitic purges led by the Communist government there and settled in the capital and in Arhus. But Danish Jewish life is above all marked by the courage of the Danish population as a whole during the Shoah, saving the vast majority of Danish Jews.

On 15 November 2022, Queen Margrethe II celebrated 400 years of Jewish history in the country by visiting the Danish Jewish Museum and attending a service at the Krystalgade synagogue in Copenhagen.

Jews of the Danish Antilles

What are today the U.S. Virgin Islands were a Danish possession from 1672 to 1916. The Danish influence remains in the architecture (notably on Saint Thomas), and in the name of places (Christiansted) and people -or in the Jewish community of the island. The synagogue of Saint Thomas, still active, was built in 1796 (reconstructed after a fire in 1833). Denmark named Jewish governors, and in 1850, half the European inhabitants there were Jewish, coming for the most part from the Dutch Antilles.

The terrifying war against Ukraine changes, of course, the function of these pages devoted to the Jewish cultural heritage of that country. Many of the places mentioned were razed to the ground by bombs. While these pages are not intended in the present time for tourism, they may be useful to researchers and students as historical references. References to so many painful histories during the pogroms and the Shoah, but also to the glorious history of Ukrainian Judaism in its cultural, religious, and Zionist dimensions. Wishing the Ukrainian people a speedy end to these atrocities of which they are victims.

Ukraine, the largest of the former Soviet Republics, is, along with Belarus and Lithuania, heir to the former “Pale of Settlement”, the buffer zone designed to contain the Jews within the westernmost margins of the Russian Empire. Despite considerable losses due to the Shoah and resulting emigration, Ukraine still contains a large Jewish community (around 500,000 members, or 1% of the population), concentrated primarily in the major cities (Kiev, Odessa, Dnepropetrovsk, Kharkov, and Donetsk) and in certain old shtetlach to the south. Jewish cultural life, in full blossom here ever since the country’s independence in 1991, nevertheless remains limited due to both the weight of seventy years of assimilation and persecution by the Soviet regime and fresh waves of emigration.

The history of the Jewish communities in the Ukraine needs to be retold in the context of the complex historical reality of Ukraine itself, which never before held the status of an independent state, except in the eras of the powerful eleventh to thirteenth-century Kiev principality (Kievskaya Rus’), shared birthplace of both the Russian and Ukrainian nations.

An evolving geography

For centuries, the history of Ukraine’s Jews was conflated with that of the Jews of Poland. From the time Poland was divided until the First World War, it was associated with that of Russia’s Jews, with the exception of Galicia, which fell within the Autro-Hungarian Empire. Since the 1917 Revolution, Ukrainian Jewish history has been tied to that of the Soviet Jews (again, except for Galicia and Volhynia, which belonged to Poland until 1939).

When the Jews were expelled from France in 1394 and later from Spain and Portugal in 1492, they were taken in by Poland. In full economic and military expansion at the time, Poland represented a host country where religious tolerance reigned for all who willfully submitted to the authority and primacy of Catholicism.

The kings of Poland, in particular Sigismund I and Sigismund II in the sixteenth century, engaged in a policy of tolerance toward Jews. They offered them certain tariff exemptions and encouraged their communities to establish institutions responsible for collecting taxes. The growth of the Jewish community throughout the fifteenth century was apparent in nearly every city of the Polish realm, especially in the central and eastern regions (such as Galicia, Volhynia, Podolia, Lithuania, and the Ukraine), where Jewish craftspeople and merchants had been immigrating for years.

Massacres of the Jewish population

This period of growth was brutally interrupted in 1648 and 1649 by the first great catastrophe to strike these communities: revolts by Khmelnitsky Cossacks against the Polish nobility. The Cossacks massacred the Jewish population of every town they captured, pogroms of an incredible cruelty that left 100,000 Jews dead throughout Ukraine.

The Jewish communities of certain cities, such as Ostrog, Sokal, Vladimir-Volynski, Uman, and Proskurov, were completely wiped out. They only regenerated many years later, but only in areas that enjoyed the protection of a nobleman of the king himself.

The birth of Hassidism

It would take an entire century after these massacres for Jewish communities in Ukraine to begin growing again, sparked by an upsurge in religious fervor marked in particular by Hasidism, a movement founded in Polodia by Israel ben Eliezer (1700-60), also known as the Baal Shem Tov of Medzihbozh. The movement has considerable success in Lithuania, Poland, and throughout Ukraine. This revival was fueled as well by the many magidim, or itinerant preachers, including the maggid of Dubno Jacob Kranz (allied with the anti-Hasidic Mitnaggedim), Dov Ber of Mezritch, Nahman of Bratslav, and other tsadikim.

In the late eighteenth century, with the repeated division of Poland in 1772, 1793, and 1795 and Ukraine’s absorption by Russia, the situation changed starkly for the Jews. Russia, which had forbidden Jews the right to reside in its territory, suddenly found itself in charge of the largest Jewish population in the world. The czarist government thus established the boundaries of a “Pale of Settlement” within which Jews were forced to settle, an area coinciding approximately with the regions taken from Poland (Lithuania, Belarus, Ukraine west to the Dnieper, the kingdom of Poland); added to these were virgin lands in New Russia (Kherson, Nikolayev, Odessa, Crimea), as well as the left bank of the Dnieper (Poltava, Kremenchug, Ekaterinoslav -renamed Dnepropetrovsk).

Development of Yiddish literature

The Russian Empire’s repressive policies persisted throughout the nineteenth century. In 1827, Jews were officially expelled from Kiev. After a period of liberal reforms under Alexander II, oppression of the Jews picked up again with Alexander III, during whose reign a number of pogroms took place against the Jewish population, driving the latter to emigrate in ever large numbers to Europe and the United States. At the same time, classic Yiddish-language literature began to develop, most notably by the writers Sholem Aleichem and Mendele Moykher Sforim.

At the end of the First World War, from 1917 to 1921, revolution and civil war tore through Ukraine. Nationalist gangs led by Simon Petliura perpetrated atrocious pogroms, massacring 100,000 Jews across the country in cities such as Zhitomir, Proskurov, Rovno, Belaya Tserkov, Kiev, and Vinnitsa. The Soviet powers, in contrast, abolished the “Pale of Settlement” and other restrictions against the Jewish community, and even supported early Yiddish theater in Kiev and Odessa. However, they simultaneously began an antireligious campaign that led to the closure of many synagogues.

Extermination during the Holocaust

By far the most traumatic event for the Ukrainian Jewish community was the Second World War and the Shoah. The Germans invaded the Soviet Union on 21 June 1941 and immediately arranged for the community’s extermination. After forcing the Jews to reside in ghettos, the Nazis liquidated these districts one by one, most often in mass public executions, and tossed the bodies of the victims in common graves dug by the victims themselves.

The location of these executions can still be found in the woods neighboring almost every Ukrainian city; they are usually marked with a stele reading “to the victims of fascism.”. An inventory of these sites would require an entire website in itself.

Rebirth of Jewish cultural life

After the war, certain Jewish communities regenerated following the return of those who managed to escape into central Russia in time, but the official antireligious and anti-Semitic policies continued; after the so-called “doctors’ plot” in the early 1950s, many synagogues and community institutions across the country were closed. It was not until perestroika in 1985 and Ukraine’s independence in 1991 that a Jewish cultural renaissance began. Increasing emigration by younger generations, however, has ultimately aged, impoverished, and weakened the community.

Until the early twentieth century, the history of Russia’s Jews unfolded primarily in territories that no longer belong to the present-day Russian federation (Ukraine, Belarus, Bessarabia, and Lithuania).

With a few rare exceptions, Jews were forbidden to settle in Moscow, Saint Petersburg, and the city of Central Russia. Of course, Jewish colonies have existed since antiquity on the shores of the Black Sea and in Crimea, and a bit later in the Khazar kingdom, which took Judaism as its main religion in the late eighth and ninth centuries. The Khazar realm soon crumbled, however, eventually replaced by the principality of Kiev, the birthplace of the Russian nation, between the tenth and thirteenth centuries. After the decline of Kievan Russia and its absorption by Lithuania and Poland, Russia’s center shifted northward to Moscow, Pskov, and Novgorod, where Jews had no right to reside. It was only after conquering Polish territories that Russia inherited its Jewish communities and, consequently, a “Jewish problem” it had never grappled with before.

In 1654, after annexing Ukraine up to the right bank of the Dnieper, Russia appropriated territories inhabited by many Jews, though the latter had in large part already been massacred in Khmelnitski. In 1721, moreover, Peter I issued a ukase expelling the Jews from “Little Russia”. This decree was reconfirmed by Empress Elizabeth Petrovna in 1742, who then forced the Jews beyond the borders of the Russian Empire.

It was therefore principally only during the three divisions of Poland (in 1772, 1793, and 1795) that Russia truly gained lands occupied by large Jewish communities -“Russia’s enigmatic acquisition”, according to the phrase coined by historian John Klier. In the span of several decades, a country previously devoid of Jews found itself governing a Jewish population 700,000 to 800,000 members strong, the largest community in the world.

In 1791, Catherine the Great took measures aimed at restricting the Jews’ freedom of movement and preventing them from settling in other regions of the empire. These measures, reaffirmed by successive monarchs between 1804 and 1825, gave birth to what was called the “residential zone” inside which Jews were forced to live; it stretched across the entire western edge of the empire, from the Baltic Sea to the Black Sea, in what is present-day Lithuania, Poland, Belarus, and Ukraine. Forbidden from working the land, moreover, Jews survived as merchants and artisans concentrated in small rural towns, or shtetlach. In addition, certain large cities, like Kiev, were off limits to Jews.

In the mid-nineteenth century, these restrictions began to soften: permission to live beyond the “residential zone” was granted in 1859 to “merchants of the first guild”, in 1860 to tenured professors at major universities, in 1865 to certain tradespeople, in 1867 to military veterans, and in 1879 to those with a higher education. Because leniency was offered only to the most affluent Jews, who were in turn attracted to the nation’s two capitals, by the late nineteenth century the highest circles of Jewish intelligentsia had left the shtetlach and moved to Saint Petersburg and Moscow.

The “Residential Zone”

“In order to live in Petersburg, one needs not only money, but also a special permit. I am a Jew. And the Tzar has set aside a special zone of residence for the Jews, which they are not allowed to leave.”

Marc Chagall, My Life, Trans. Dorothy Williams (London: Peter Owen, 1965).

It was not until 1917, however, when the “residential zone” was abolished, that this became a mass movement. Large communities of Jewish intellectual and artists began settling in Petrograd (St. Petersburg) and Moscow, raising cultural life in those cities to new heights during the 1920s. A major catalyst was the Jewish State Theater (GOSET) founded by Alexander Granosky and Solomon Mikhoels. The Bolsheviks of the era supported Yiddish as an expression of the popular Jewish classes and encouraged the theater’s development in Minsk, Kiev, and Odessa. Jewish schools teaching in Yiddish began to appear (there were 1100 of them in Russia by the early 1930s), while Jewish sections started opening at the universities.

Russian Jewish Theater

The origins of Yiddish-language theater in Russia dates to the nineteenth century and evolved primarily out of Purim-spiele, plays retelling the story of Esther. The father of Yiddish theater was Abraham Goldfaden (1840-1908). This basically traveling form of theater began to take off and the Revolution of 1905, thanks to Peretz Hirschbein, who established in Odessa the Jewish Artistic Theater, where “classics” by Itzhak Leybush Peretz, Sholem Aleichem, and Shalom Asch were performed, along with plays of his own. With the Revolution of 1917 and during the 1920s, Yiddish theater moved through a second phase: Alexander Granosky (1890-1937) founded the Jewish Studio in Petrograd, where he discovered Salomon Mikhoels, a cult figure in the world of Jewish and Soviet theater. In 1920, Granosky’s troupe moved to Moscow and became GOSET (the Jewish State Theater), which garnered fame with the help of set designers such as Chagall, Altman, Rabinovitch, and Faltz.

The Soviet regime viewed the “jewish question” largely in socio-economic terms, and sought to gain the support of the Jewish masses by offering them land, previously forbidden to them under the czar. It also offered them a secular, Soviet Yiddish culture but repressed Hebrew culture. In the 1920s, Jewish kolkhozes began concentrating in southern Ukraine and Crimea, within regional Jewish districts. In 1928, the Far East region of Birobidzhan was declared an autonomous Jewish region with Yiddish as its official language and open to all Jews willing to colonize it. At the same time, however, Zionist activities were prohibited, including the He-Halutz, Makkabi, Ha-Shomer ha-Tsair organizations, the Poalei Tsion Party and, in the name of atheism, anything else pertaining to religion, including synagogues, yeshivot, hadarim, and mikva’ot.

In the mid-1930s, the government’s antireligious policies worsened: from 1937 to 1939, at the height of Stalinist oppression, practically every Jewish institution and organization was prohibited, with a large number of Jews falling victim to purges, deportations, and executions. In 1939, more than 3 million Jews lived in the Soviet Union, a number that climbed to 5 million after the annexation of eastern Poland following the German-Soviet nonaggression pact.

On 22 June 1941, Nazi Germany surged across the Soviet Union and exterminated the Jewish population in the occupied territories, which corresponded approximately to the former “Pale of Settlement”. Between the summers of 1941 and 1942m Jews were executed by the hundreds of thousands, city by city and town by town, then tossed into mass graves -all this before the “clean” death in the gas chambers had been invented in Poland.

In 1942, the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee was founded under the leadership of actor Solomon Mikhoels, designed to sensitize and alert international opinion to the Nazi massacre of the Jews. Most members of this committee were arrested and executed in 1952.

Beginning in 1948, anti-Semitism became official government policy, in the guise of the struggle against “cosmopolitanism”. All remaining active synagogues, Jewish theaters, libraries, and Yiddish presses were shut down. Jews who held high positions were dismissed, such as the famous photographer Evgueni Khaldei, who snapped the famous photo of the Soviet flag flying over the Reichstag. Great Yiddish writers were murdered -Peretz Markish, Der Nister, David Bergelson, and others.

After Stalin’s death and a slight thaw under the Khrushchev regime, Jews accused of so-called “doctor’s plot” were pardoned, and a Yiddish-language review, Sovetish Heymland, was allowed to appear beginning in 1961. After the Six Day War of 1967, official anti-Semitism reappeared in the form of anti-Zionist and hostility toward the state of Israel. Soviet Jews who asked to emigrate were flatly denied, such as Anatoly (Natan) Shcharansky, who later became the Israeli Minister of Housing.

It was only in the late 1980s, under Mikhail Gorbachev’s perestroika, that the situation improved for Russia’s Jews, who were finally permitted to practice their religion and cultural activities and given the right to emigrate. Many synagogues and Jewish schools reopened across Russia and the former Soviet republics, and a hundred or so Jewish Russian-language newspapers and periodicals were founded besides a host of other Jewish organizations, congresses, and communities. In Moscow and Saint Petersburg, “Jewish Universities” were established, along with the Judaic Institute in Kiev, near the Mohyla Academy. The massive emigration of Russian and Soviet Jews that began in the 1990s has abated somewhat today. Yiddish is no longer much spoken, and the Sovetish Heymland shut down operation in 1992.

The Estonian Jewish community is the smallest of the Baltic states, and, historically, the one that played the least important role in Yiddishland before the Shoah. Indeed, the community never counted more than 4,500 members.

Although present in Estonia since the fourteenth century, the Jews did not assume permanent residence in Estonian territory until after 1865, when the czar abolished the decree forbidding them to live there.

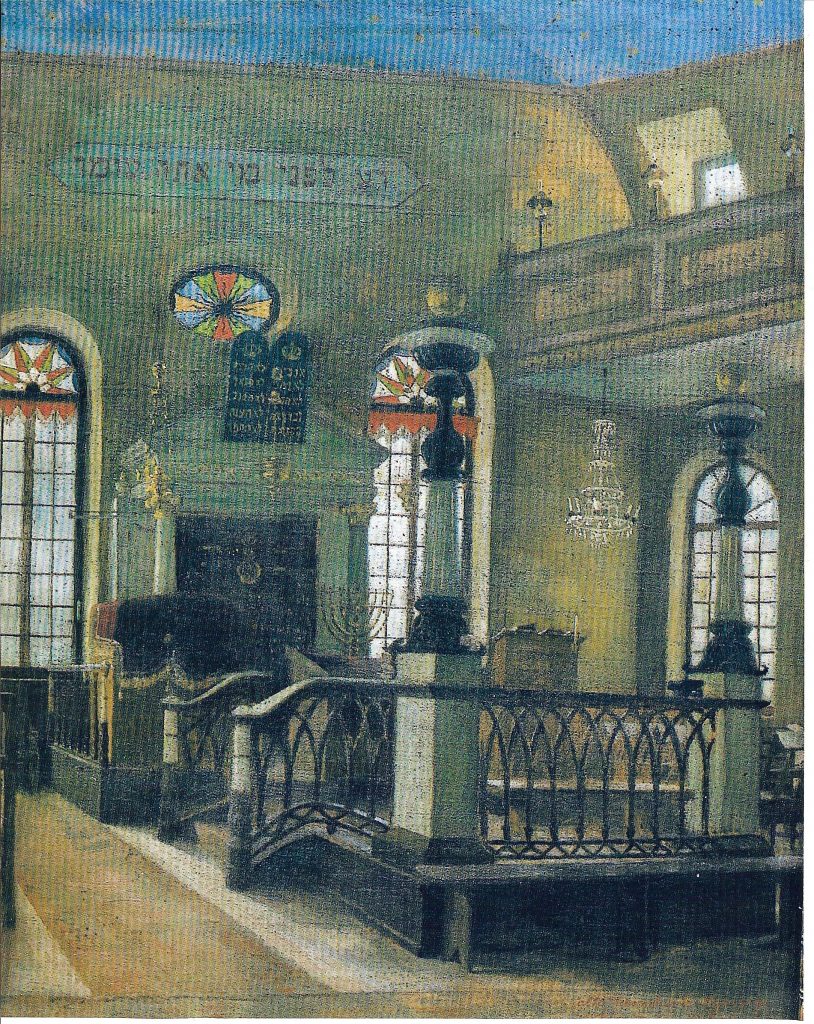

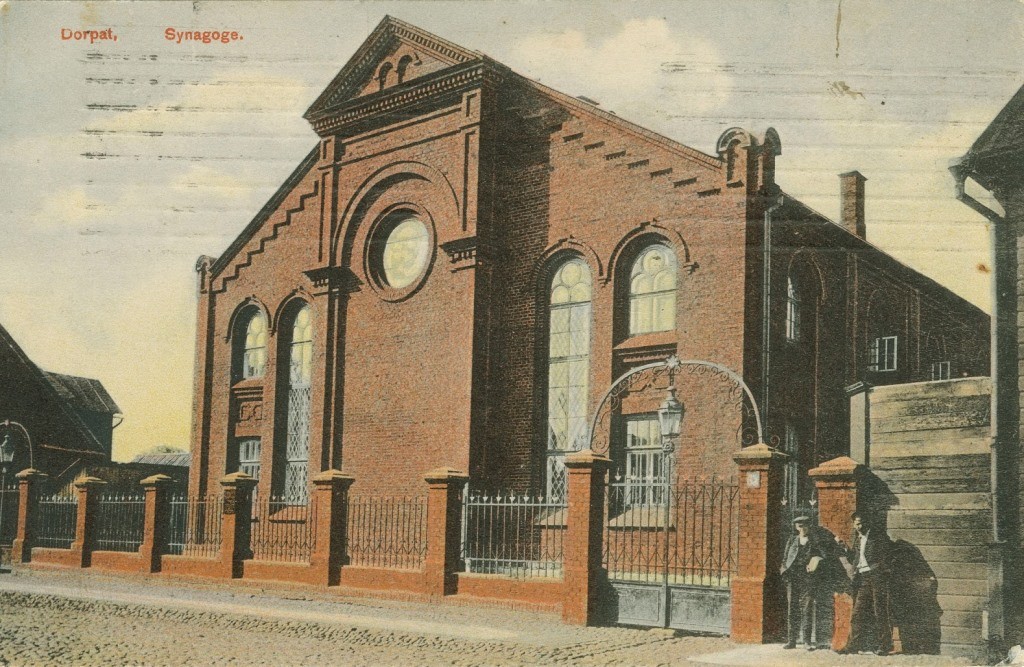

The cantonists, Jewish soldiers serving in the imperial army, established the community in Tallinn in 1830; that of Tartu was begun in 1866. Synagogues were built in the two cities in 1883 and 1900, respectively; both burned down during the Shoah.

Nothing remains of the small Jewish communities of Narva, Valga, Pärnu, and Viljandi, which were destroyed during the war. Jews in Estonia today are in large part Russian-speaking Jews who arrived after 1945.

During the interwar period, independent Estonia treated its Jewish minority fairly. Jews enjoyed all the civil liberties granted to other Estonian citizens, and beginning in 1925, cultural autonomy as well. A minority chose to settle in Palestine, where they contributed to the foundation of two famous kibbutzim: Kfar Blum and Ein Gev.

The 1940 Soviet occupation of Estonia put an end to all Jewish communal life: 400 Jews were sent to work camps. The Nazi invasion in July 1941 succeeded in exterminating the community, whose members were killed by the Einsatzgruppen with the active complicity of local collaborators, most notably militants from the Omakaitse Fascist movement.

After 1945, the Soviet state outlawed all forms of Jewish cultural activity; all that remained was a small community that maintained the cemetery of Tallinn (which still exists). In contrast, one of the effects of anti-Jewish Soviet policy in terms of higher education was that Jewish students from Moscow, Leningrad (Saint Petersburg) and Kiev went for their studies to the University of Tartu or the Polytechnic Institute of Tallinn, which were considerably more open.

Also, during its Soviet occupation, Estonia was a relatively accessible open door for the refuseniks heading toward the United States or Israel. The Jewish community in nearby Finland had helped and continues to aid many Estonian Jews.

Jewish life in Estonia began again in 1988 with the creation of a Jewish Cultural Society and later a school in one of the locations of a former Jewish gymnasium. Since Estonia’s independence in 1991, the Jewish community has become openly active. It scarcely numbers 1,000 people (mostly of in retirement age) according to official Estonian sources and 3,000 according to Jewish sources.

In October 1993, a law granting economy was passed. Unlike the tendencies in Latvia and, to a lesser degree, in Lithuania, the former Estonian Waffen SS receive absolutely no official or public support, and the extreme right is hardly visible.

Interview with Shmuel Kot, Chief Rabbi of Estonia

Jguideeurope: How do you perceive the evolution of the Jewish community in Estonia since you moved there more than twenty years ago?

Shmuel Kot: The community is growing from different perspectives. Religiously, culturally and on the organizational level also. The synagogue has been located in a contemporary building for the last 15 years. We have nice activities every Shabbat, with different kinds of guests invited to participate. During the holidays, we provide lessons for Talmud Torah for children as well as for adults.

Do you feel that the community has developed a more professional and official role with its development?

Yes, definitely. Jewish life today offers a vast diversity of possibilities to be enjoyed. Most of our members are Russian speakers, but we also have an important group of French members. Just before COVID, due to the growing number of French members, someone donated twenty prayer books in French-Hebrew. Jewish life is very different in the winter and the summer. During the winter, there is almost no daylight. People are more active inside. During the summer, Shabbat can start sometimes at 11PM! The night of Shavuoth where Jews study all night, has also to be readapted. Life is very nice here. People can be Jewish very openly, there’s no anti-Semitism, and the relationship with the Muslim minority is also good.

Are there new ways of sharing Jewish heritage?

The country makes many efforts in its sharing. And places related to the bright and dark pages of that heritage are shared today. The oldest cemetery was destroyed by the Russians a long time ago. A new cemetery has been opened and is still used today. The Jewish Museum offers a good description of that evolution, displaying the early history of Jewish life in Estonia in the 19th century with young Jewish soldiers settling, the era of prosperity of Jewish cultural life between the two World Wars with, for example, the Maccabi events and the tragedy of the Holocaust.

Estonia was both the first country to grant Jews cultural autonomy in the 1920s, and, on the other side, the first to declare itself Judenfrei during the Holocaust! The museum also displays Jewish life during the Soviet era.

Are you often contacted by persons outside of Estonia wishing to know more about Jewish historical facts and questions about genealogy?

Every day! People contact us for various research. Some archives that we have made available to the public and others that are kept by local authorities, which we try to obtain for them. The Estonian government is making many efforts to enable the gradual availability of those documents online. We just discovered that someone in our synagogue was adopted and found out his Jewish roots thanks to such documents.

The Jewish community of Latvia traces its origins to the middle of the fourteenth century. It developed in the principalities of Kurland and Livonia, territories that have often changed hands. The presence here of Baltic barons contributed to the Germanization of the country and placed the Jews themselves under this cultural influence.

The gradual annexation of the country by the Russian Empire weakened the Jewish presence, since only Jews who could prove to have lived there before it was absorbed by the Russian Empire were authorized to stay.