Portugal became an autonomous kingdom under Afonso Henriques (1109-85), son of Henry of Burgundy, a prince of French origin. The history of its Jewish population differs from that of the other Jews on the Iberian Peninsula. Afonso I was aware of the importance of the Jewish communities he had freed from the Muslim yoke and granted them his protection, putting the chief rabbi, Yahia ben Yahia, in charge of collecting taxes.

Until the end of the fourteenth century, the Jews were reasonably well protected. The rivalry between the two Iberian kingdoms resulted in the accession of a new dynasty, the Avis. Their reign began a period a great prosperity for the Portuguese Jews, whose ranks were soon swelled by the Spanish Jews who began to arrive in 1391. This golden age for the Jews paralleled Portuguese exploration of Africa and the East Indies, which anticipated the “great discoveries”.

In 1279 the country had thirty-one judarias. Two centuries later there were 135. However, this period was not totally free of tension between Jews and Christians: Portugal’s new merchant class was apprehensive of the influence of the Jews and their capital.

Under the reign of João I (1385-1443), new laws obliged Jews to wear an identifying sign on their clothes and imposed curfews on the judarias. There were scattered outbreaks of violence, like the attack on the Lisbon judaria in 1445, in which many died. Many Jews subsequently converted. When the Catholic monarchs passed their edict of expulsion, King João II allowed the Jews to enter Portugal, offering a limited stay of eight months on payment of eight cruzados per head. Portugal estimated Jewish population of 30,000 was thus swollen by some 30,000 to 60,000 Spanish Jews, the new total representing between 6 and 10% of the kingdom’s entire population.

Until 1496 the Portuguese government steered an ambivalent course between the need to conciliate its powerful neighbor and a concern to keep a still-useful minority within its borders. After a series of extremely harsh measures, with children being separated from their parents to be brought up in the Christian faith, and considerable pressure on adults to convert, a decree of expulsion was issued in December 1496. However, lacking the number of ships needed to ensure their departure, King Manoel I decided to convert all the Jews to Catholicism in one comprehensive ceremony.

Furthermore, in 1499 he closed the border to prevent them from crossing. He thus created a society of cristãos novos (new Christians) whose destiny was quite different from that of the Spanish conversos. For, in spite of the apparent unity of the two Iberian kingdoms, their ways of dealing with their Jewish population were very different.

These “new Christians” formed an homogenous group who occupied important positions in Portuguese society while continuing to maintain their own cultural traditions. They came to form a separate nation, and they were called “men of the nation”, or, after settling in Bayonne and Bordeaux, “Portuguese nation”.

The Inquisition of 1547 authorised the prosecution of cristãos novos who still practices Judaism and, later, of the crypto-Jews.

It was carried out with varying degrees of conviction. The union of the two kingdoms from 1580 to 1640 under Philip II of Spain facilitated contact between conversos and cristãos novos, who were linked by family and commercial networks far beyond the peninsula to Bayonne, Bordeaux, London, Amsterdam, and the Ottoman Empire, where the Portuguese-Jewish diaspora was present.

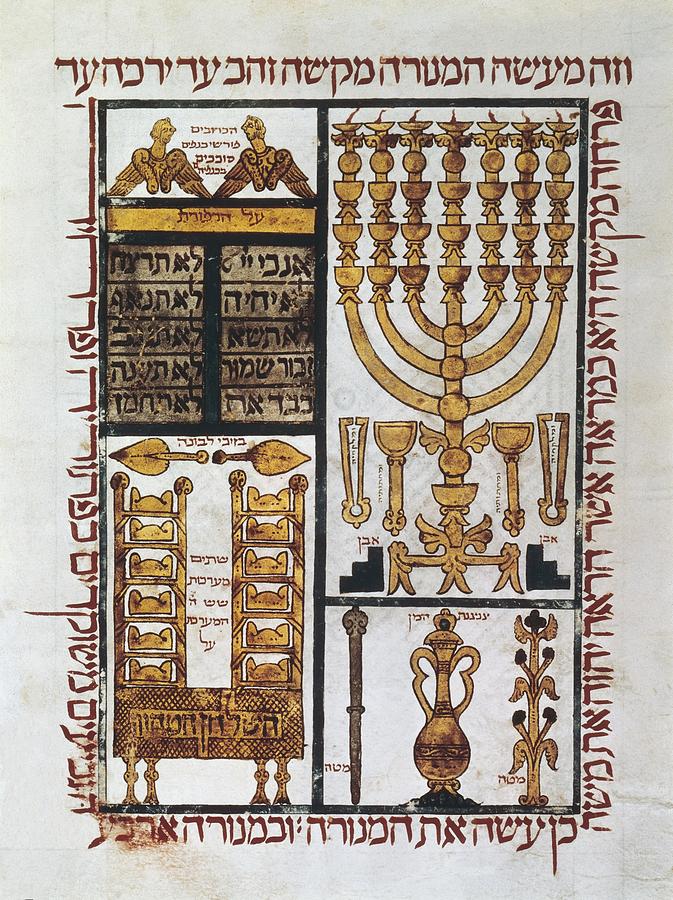

Portuguese exploration opened new horizons for the kingdom, not least for the Jews, many of whom settled in the Americas. They also participated intellectually in this auspicious period: the rabbi Guedella Negro was made physicist and astrologer to King Don Duarte for the period 1433-1451; Jafuda Cresques, also known as Jaime of Majorca, the son of the cartographer and inventor of instruments of navigation Abraham Cresques, was asked by the infante Henry the Navigator to train navigators; Abraham Zacuto, from Castile, published a perpetual almanac in 1496 used on many voyages, including Vasco da Gama’s to the East Indies in 1497. Printing works flourished, including those of Eliezar Toledano in Lisbon and Samuel Orta in Leiria.

Interview with Jean-Jacques Salomon, vice-chair of the Hagada Association, in charge of the Tikva Jewish Museum of Lisbon

Jguideeurope: Recently, there has been a growing interest in Portuguese Judaism, has this helped the evolution of the Tikva Museum project?

Jean-Jacques Salomon :There is no doubt that the multiplication of scientific and historical research and publications on the subject of Portuguese Jewry associated with that of the Crypto-Jews, especially in Europe and the United States, has triggered a growing interest at different levels of the Portuguese, but also European and American cultural and educational world.

In Portugal, the municipalities, especially those involved in the Red de Judarias, the Ministry of Culture (which awarded our Association the label of “Cultural Interest”) and even the Presidency of the Republic, are all showing interest. Obtaining the label of Public Utility for our project is considered a formality. The strong development of cultural tourism in Portugal, before and after the pandemic, has also played its part.

How did Daniel Libeskind become involved in the project and what is his architectural vision for the Museum?

Following the proposal of the Lisbon Municipality in March 2019 to award us (at the time we were simply the representatives of the Association of Friends of the future Alfama Museum) a plot of land of more than 6,000 m2 facing the Tagus and the Belem Tower, we immediately decided to raise our ambitions. Calling on a great international architect was the first step. An appearance at the Congress of American Jewish Museums (CAJM) in March 2019 put us on the path to Daniel Libeskind.

His visit to Lisbon two months later convinced us and the representatives of the Lisbon Municipality that he was the right man for the job.

What was Libeskind’s architectural vision for the museum and how was it received by the Portuguese authorities?

In line with much of his work on the duty to remember, as symbolised by the fractured plans of the Jewish Museums in Berlin, Dresden, San Francisco and Manchester, Daniel, on his first visit to Lisbon, imagined reproducing the word Hope (Tikva) in the Museum building. One of the most representative of the thousand-year-old history of Portuguese Jews, made of Light and Shadow. His first sketches in October 2019, making the letters of Tikva, in Hebrew, the only dividing walls of the building, immediately won over the representatives of the Lisbon Municipality and the Hagadá Private Law Association, created to develop the new project.

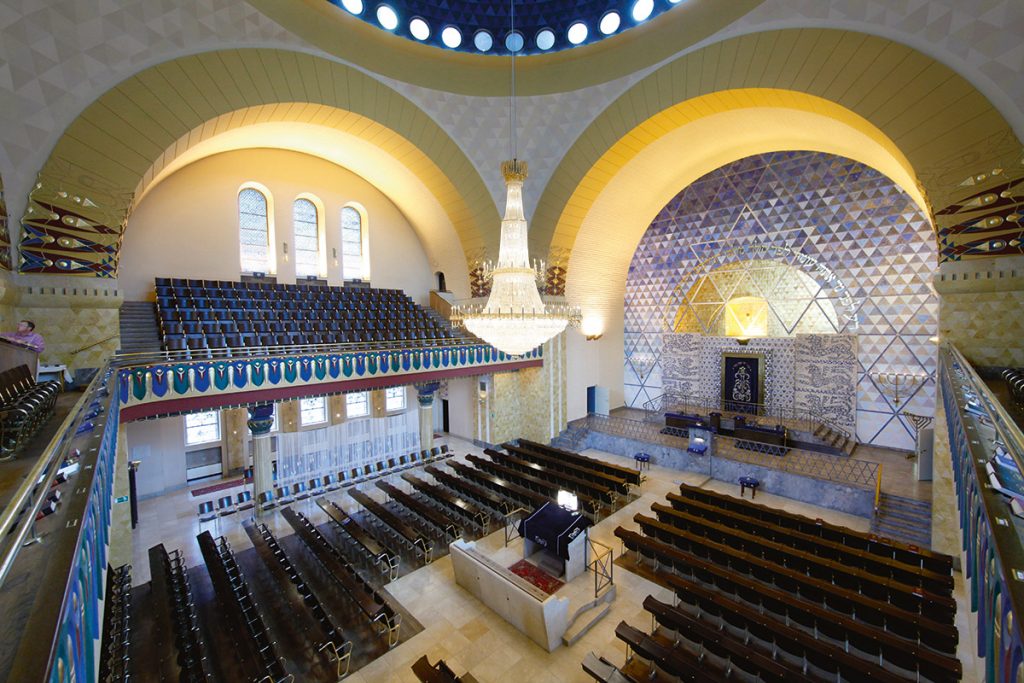

Yet it was not until the nineteenth century that Portugal’s Jews were able to express their identity openly and live freely. Between 1820 and 1830, Jewish families from Morocco came to live in Algarve and in the Azores. In 1860, a synagogue was built in Faro. In 1904 the Shaare Tikvah (Gates of Hope) Synagogue, still in use today, opened in Lisbon. In 1920 Captain Barros Bastos founded the Jewish community of Porto and embarked on a campaign to persuade crypto-Jews to return to the Judaism of their ancestors. Working almost single-handedly, he organised circumcisions, published a journal, held talks, set up a school a built a superb synagogue. Opened in 1936, it continues to be used for worship. Unfortunately, Bastos was attacked by Portuguese fascists and a military tribunal condemned him on trumped-up charges; only in 1997 was his name rehabilitated. During this same period the engineer Samuel Schwartz made the surprising discovery of a crypto-Jewish community in Belmonte (Guarda province), all but forgotten by both Judaism and history.

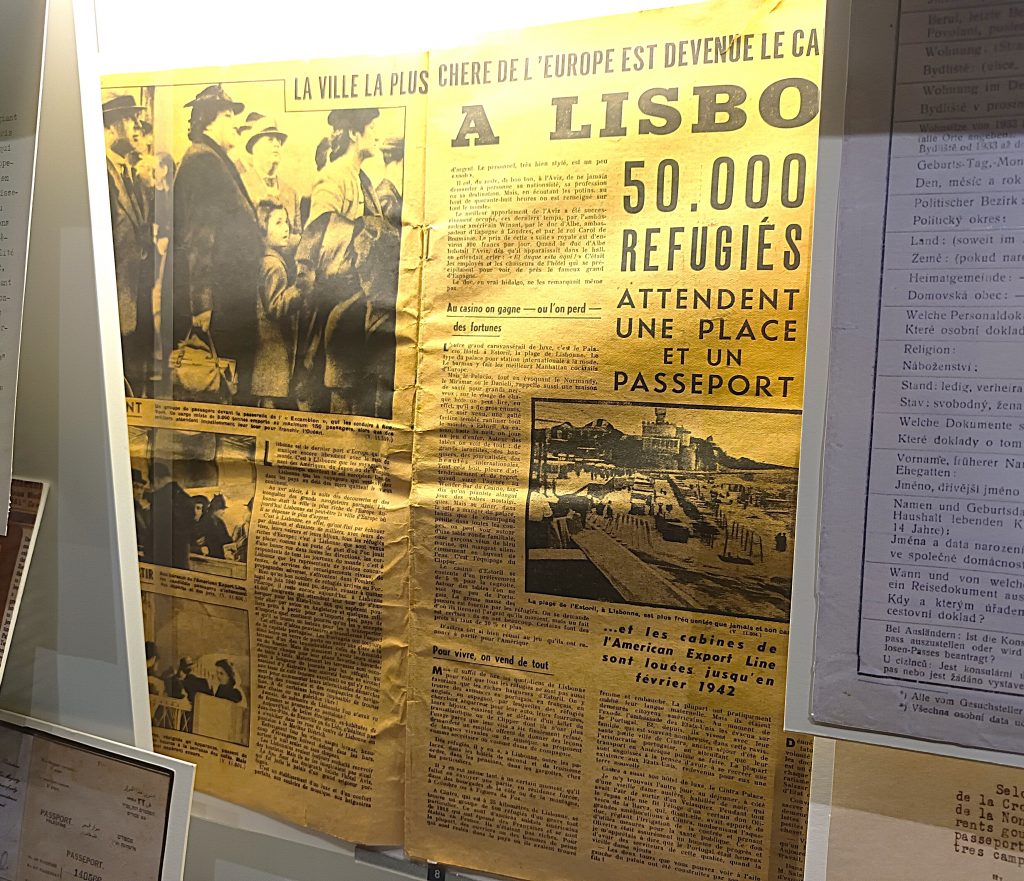

After his posting to Bordeaux in 1940, the consul Mendes Sousa perceived the Nazi threat and set about providing visas for refugees. His work during the weeks of the French collapse saved several thousand mens and women from death. He was nonetheless discharged and discredited by the authorities, and died in poverty. In spite of Salazar’s sympathy for the Nazis, Portugal remained neutral during the war and protected Portuguese Jews while providing support for those who managed to cross its borders. In 1948, with the agreement of the government, the American Jewish Joint Committee set up a camp to receive and organise the transit of Jews to the United States.

In 1977, the new Portuguese democracy established diplomatic relations with Israel. In 1993, the first stone was laid for the Belmonte Synagogue. It opened in 1996 as part of the ceremonies commemorating the expulsion of December 1496. Today, there are several thousand Jews living in Portugal, mainly in the major communities of Lisbon, Porto, and Belmonte but also dotted around a few other towns.

Created in 1992 by Anne Lima and Michel Chandeigne, the Chandeigne publishing house specializes in travel writings and the Lusophone world. It has published many works of reference on Jewish heritage by authors such as Carsten Wilke, Samuel Schwarz, Yosef H. Yerushalmi and many others in its collection “Péninsules”. Celebrating the many events occuring this year in Portugal, we have interviewed Anne Lima.

Jguideeurope: Where did the idea come from of enabling your readers to (re)discover the Portuguese Jewish Heritage?

Anne Lima: It’s through our work on the history of European naval expansion, particularly with our collection « Magellane », that we became interested in the encounter between the three monotheistic religions and the three cultures which have lived together for centuries in Spain and Portugal. Our series “Péninsules”, which has been created almost 20 years ago, is dedicated to the study of that cohabitation. While we studied the inter-religious outlook, it was impossible not to notice the extraordinary richness of the Jewish culture in Portugal, of which certain aspects of this history remain little known and differ very much from its neighbor, Spain. Concerning the Marranos for example, the history, development and heritage reveal a very special Portuguese feature, thus leaving multiple traces, notably in the North of the country where many crypto-Jewish communities have been discovered in the early 20th century.

As you claim, the study of the Marranos phenomenon is a difficult topic and quite different concerning each country. Among the books you publish on that topic, we can find Sefardica, written by Yosef H. Yerushalmi. Why did it become a canonical study of the Marranos phenomenon?

First of all, as we know today, Yerushalmi’s contribution goes way beyond Jewish studies. Sylvie-Anne Goldberg, referring to his book Zakhor, claims that Yerushalmi « has initiated a vast examination of history’s role in modern societies, by questioning its relationship with collective memory ».

Regarding the Marranos, one of Yerushalmi’s biggest credits, as is pointed out by Yosef Kaplan is the breaking down of barriers he undertook by contextualizing the Marrano epic within the crisis of European conscience at the beginning of the modern era. For example, in one of the articles included in Sefardica, « Assimilation and racial anti-Semitism: the Iberian model and the German model », Yerushalmi doesn’t hesitate to draw parallels between the politics of blood purity and the Nazi definition of a Jew: « The purity of the blood substituted for the purity of the faith. » Finally, according to Nathan Wachtel. Yerushalmi is a pioneer when he underlines both Marrano modernity and that of the Iberian inquisitorial system, to the extent that the denunciation system as well as the inquisitorial methods heralded the police rationality of contemporary totalitarian regimes.

Which place linked to the Portuguese Jewish heritage has had a particular impact upon you?

My discovery of the Jewish and Marrano world in Portugal occurred in the 1980s. It was the result of my history studies, as well as of a friendship with Livia Parnes who at that time prepared a PhD on the Marranos in Portugal and of a family rooting in Beira Alta, a region presenting a rich Jewish and Marrano heritage. The three cities or villages which have left the biggest impact upon me and gave me the will to expand our series “Péninsules”, are Belmonte, Trancoso and Guarda.

The incredible story of the discovery of Marrano families in the village of Belmonte in 1917 by Samuel Schwarz, a Polish mining engineer, was undoubtedly decisive for this place all along the 20th century and continues to be so today. The impact of this Discovery goes beyond the religious phenomenon: it affects the social and political relations of the city, changes the cultural landscape, contributes to academic research (new chairs in the region) and influences tourism and financial investments. Nevertheless, the discovery wasn’t limited to Belmonte. Samuel Schwarz’s discovery was followed in the 1920s by an extraordinary movement of “return” of the Marranos to Judaism, entitled « Work of Redemption ». It was carried out during many years by an outstanding man, Republican captain Artur Carlos de Barros Basto. Residing in Porto, he led the movement which had an immense effect and left tangible traces in numerous cities and villages in the regions of Beira Alta and Trás-os-Montes, such as Trancoso, Bragança (where one can stroll down the Rua dos Judeus), Covilhã, and Porto (the Mekor Haïm synagogue, konwn today as the Kadoorie synagogue, was built at that time).

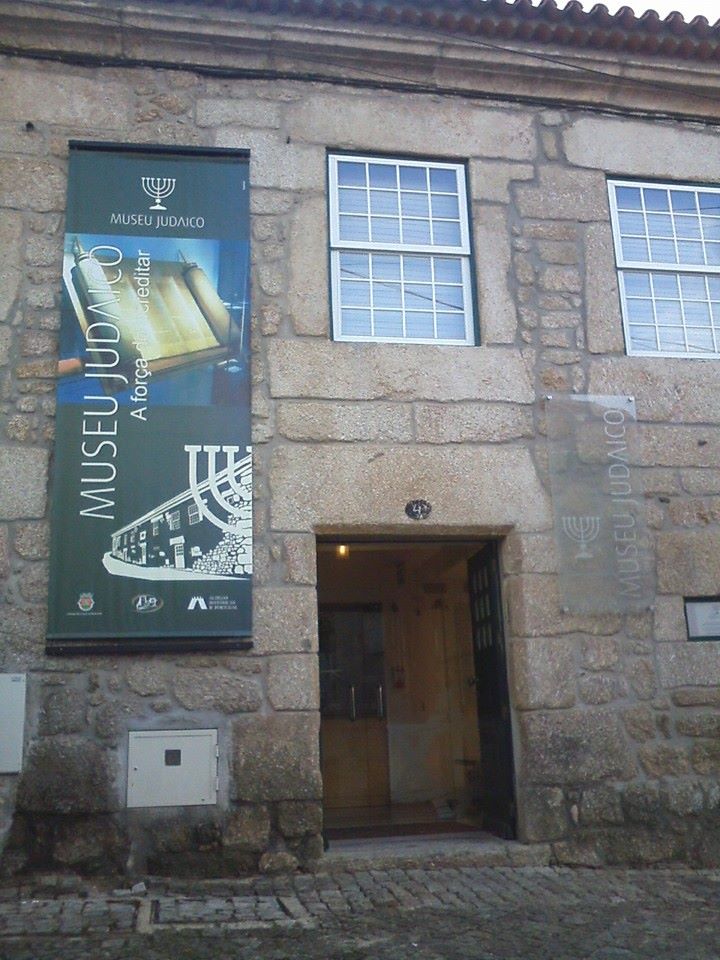

Tomar, in the region of Santarém, is yet another place where Jewish cultural heritage is particularly striking. In that city of the Templars, we can find what seems to be the oldest synagogue of Portugal, dating back to the 15th century, before the forced conversion of the Jews (1497). The building was discovered by Samuel Schwarz (in 1923), and it’s again thanks to him that such an exceptional heritage was saved. Despite many incidents, and after long years, the synagogue was completely restored and solemnly inaugurated this year in the presence of representatives of the city and Jewish studies specialists.

Can we notice differences among the cities concerning such curiosity and will to share?

No doubt. The jolts in Belmonte which already started in the 1920s and even more so in the 1980s, after the (re)discovery of the Marranos, have given rise to the creation of an embryonic Jewish community, with all the particularities and the complexity it entails.

On the other hand, cities such as Tomar or Castelo de vide, where Jewish history and heritage are very ancient, experience only a touristic appeal and have been completely deserted by Jews for numerous years.

Has granting the citizenship to descendants of Portuguese and Spanish Jews who request it changed the perception and attendance levels of this cultural heritage?

Since the law has come into effect, we reckon that more than 37,000 Sephardic Jews have requested the Portuguese citizenship. Most are between 20 and 45, coming from Turkey and Israel, but also from Brazil, Argentina and the US. So far, almost 8,000 of them have obtained a Portuguese passport. Of course, such a passport makes it easier to enter European soil. According to some Jews in Porto and Lisbon, the impact of the Law is already « visible », particularly by a kind of “Jewish tourism” which it enhanced. One can indeed regularly read in Portuguese newspapers accounts on visits and visitors who come in situ in a way in order to assess the would be commitments and engagements involved (regarding to rights, taxes, etc.).

Belmonte remains an emblematic case. This new form of tourism forces the municipal authorities to take initiatives as the return on investment may prove to be rewarding. The main problem being, in Belmonte as well as Tomar, that there are probably not enough resources yet. Thus, we witness punctual operations, deprived of any global thinking, or a structured program for the long term. Finally, the situation in Belmonte is undoubtedly more complex, from the perspective of the Community leadership and the religious representatives. The rabbis often stayed too short of a time in order to grasp the high stakes which represent the needs of this particular community.

There are numerous legends surrounding the arrival of the Jews in Spain. They were propagated by Jewish and Christian chroniclers, especially in the sixteenth century. Some say they came in the time of King Solomon, following in the wake of the Phoenician sailors; others that the event was one consequence of their exile from Judaea, as ordered by Nebuchadrezzar.

Historians, for their part, specify that the first Jews came here in a relatively organised way after the destruction of the Temple in Jerusalem, in 70 C.E. They settled first on the Mediterranean coast, then spread throughout most of the Iberian Peninsula. The oldest physical evidence of the Jewish presence in Spain is a trilingual inscription (in Hebrew, Latin, and Greek) on a child’s sarcophagus found in Tarragona and dating from the Roman Empire (now displayed at the Sephardic Museum in Toledo). Further, there is no doubt that the mosaic at Elche (first century) originally decorated the floor of a synagogue. This is attested by the Greek inscriptions and the nature of its geometrical drawings. Finally, texts reveal a Jewish presence in Spain during the same period: examples are The War of the Jews by Flavius Josephus (VII, 3, 3) and the Mishna (Baba Batra, III, 2).

Sepharad: Jewish Spain

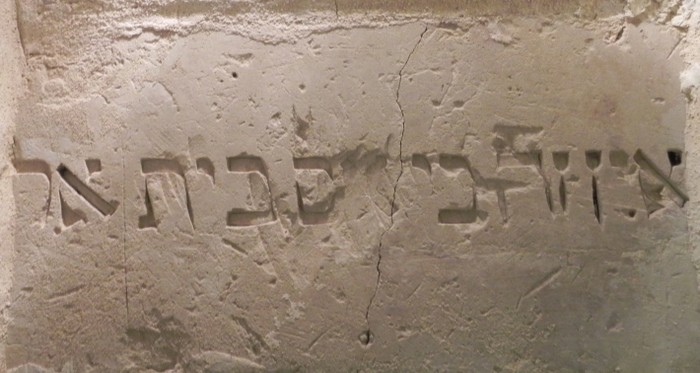

The term “Sepharad” appears in the Bible (Obadiah 20, King James version): “And the captivity of this host of the children of Israel shall possess that of the Canaanites, even unto Zarephath; and the captivity of Jerusalem, which is in Sepharad, shall possess the cities of the south”. Since the eighth century, “Sepharad” has traditionally referred to Spain and the Spanish Jews, and, by extension, has been applied to all the Jews in the communities around the Medeiterranean.

Little is known of the Spanish-Jewish communities before the eighth century. Under the Romans, the Jews had the same status as elsewhere is the empire. Under the reign of the Visigoth kings, who were Aryans, the Jews were tolerated and many lived from farming. From 586, when King Recaredo converted to Christianity, the Jews endured nearly a century of persecutions and forced conversions (making them the ancestors of the Marranos). King Egica even considered making them slaves.

When the Arabs came in 711, the Jews cooperated with them. The Arabs were few in number and in need of faithful allies. It was in the interest of both communities to get along, especially since large numbers of Jews from the Maghreb soon swelled the ranks of the Moors and the Jews of the Sepharad. The importance of the Jewish minority is reflected in the appellation “Jewish cities” some Arab geographers gave to Granada, Tarragona, and Lucena. The development of urban life called for shopkeepers and administrators, functions Arabs and Berbers were loath to take on.

The institution of the caliphate of Córdoba in 926 ushered in a golden age for Judaism in the Islamic lands. Abderrahman III (912-971) took as his doctor Hasday ibn Saprut, a Jews from Jaén, entrusting him not inly with his personal health but also with diplomatic missions such as contracts with the abbot of Gorze and negotiations with the emerging kingdoms of León and Navarre. Hasday became a rich courtier and his life was sung by the poets Menahem ben Saruc and Dunas ben Labrat. He organised the translation of numerous works of science from Greek into Arabic and contributed greatly to the cultural prosperity of his community. The example of Arabic poetry inspired Jews to write superb poems and to study grammar. All this intellectual ferment favored the growth of a rich Hebrew culture.

In the eleventh century Granada was the capital of Arab Spain. Samuel ha-Nagid, known as Nagid (993-1056), was the key figure in this period. This tradesman from Malaga quickly rose to become the vizier charged with conducting Granada’s policy and leading its Arab army, notably against Seville and Almería. Nagid was also a poet and learned rabbi and did much for the arts, especially poetry. The same was true of his son Yosef, who succeeded him at his death.

These poets give us an idea of the degree of development of the Jewish communities in the Islamic lands and of the way of life of courtiers there, divided between their love of pleasure, literature and the arts, and their traditional religion? They would later serve as a model for Jews in Castile and Aragón.

Salomon ibn Gabirol

The great poet Salomon ibn Gabirol (1022-54), the protégé of Nagid and his son, wrote the 400-line Kingdom’s Crown, a contemplative hymn to God and His creation, which Sephardic communities used as part of the liturgy for Yom Kippur. He also wrote The Source of Life, a philosophical work in Arabic examining the principles of Neoplatonism, which the Muslims were then reintroducing. He is also credited with Adon Olam, the prayer recited several times during daily services in the week and at the Shabbat by Jewish communities all over the world:

“Reigned the Universe’s Master,

Ere were earthly things begun;

When His mandate all created,

Ruler was the name he won.

And alone He’ll rule tremendous

When all things are past and gone,

He no equal has, nor consort,

He, the singular and lone,

Has no end and no beginnings;

His the scepter, might and throne.

He’s my God and living Savior,

Rock to Whom I in need run;

He’s my banner and my refuge,

Fount of weal when call’d upon.

In His hands I place my spirit,

At nightfall and at rise of sun,

And therewith my body also;

God’s my God -I fear no one”.

The New Encyclopedia of Judaism, Ed. Geoffrey Wisoder (New York: New York University Press, 2002).

However, with conflict with Arabic kingdoms and pressure from the Christians, especially after the reconquest of Toledo in 1080, the Spanish Arabs were driven to appeal to the Almoravids of North Africa for help. When the latter invaded southern Spain, the Jews only just avoided forced conversion. But the Almohads of Morocco, who invaded in 1146, were more intransigent: they prohibited the practice of Judaism, forcing Jews to either convert or hide their religion. Others chose exile in the neighbouring Christian lands. Apart from Granada, the last Moorish kingdom, Islamic Spain began at this time to lose its Jews.

In all, Christian Spain took seven centuries to win back the Islamic territories. The recovery was completed with the capture of Granada in 1492, an event that deeply marked Jewish-Christian relations. In parallel to the victories won by the kingdoms of León, Navarre, Aragón, and Catalonia, the old Jewish communities of Catalonia and Aragón began to grow, and small groups settled along the road to Santiago de Compostela. The Jews colonised the reconquered territories and played an active part in trade and the textile industry.

In 1085 Alfonso VI took Toledo, establishing the new frontier between the Cross and the Crescent. The Jews were protected by the Christian monarchs, for they made useful administrators of the new territories as well as tax collectors and facilitated contacts in Arabic. The Jews grew wealthy. As the finance ministers of Castile and Aragón, it was they who advanced the tax revenues to the king.

By the twelfth century, all of Spain apart from Granada was Christian. A new golden age began for the Spanish Jews, but in the Christian lands now. This was especially true under Alfonso X (“the Wise”) in Castile and Jaime I in Aragón. Toledo became a new Jerusalem, the capital of Jewish life. It was home to scholars, Talmudists, chief rabbis, and financiers. Catalonia, too, had a period of splendour with Nahmanides at Gerona and Salomon ben Adret at Barcelona. The Jews kept out of political life and were no threat to relations between Christendom and Islam. In legal terms, they belonged to the king, a status that gave them protection but also put them at his mercy.

As elsewhere in Europe, the power of the church grew as the reconquest spread. Although the Fourth Lateran Council (1215) decreed a number and anti-Jewish measures, they were implemented with a certain flexibility for reasons of political necessity and in the interests if the struggle against the remaining Moorish kingdoms. Nonetheless, in Aragón, Jews were excluded from public service, and in Castile, the Cortes made numerous propositions to limit Jewish freedom.

The Black Death, the influence of anti-Jewish polemical literature, and the effect of Jewish participation in the civil war between Peter the Cruel and his bastard brother, Henry of Trastamare, all contributed to a rejection of Judaism.

This was compounded by a decline in faith and slackening of moral and religious practice among the better off. The Jewish-Christian dialogue entered a new phase, and the Christian world began to consider conversion as the solution to the presence of the Jewish minority. This is the time of the famous Barcelona Controversy (1256), when Nahmanides’s victory over the converted Jew Pablo Christiani was only partial. The ground had thus been prepared for the explosion of violence orchestrated by the archdeacon of Ecija, Ferran Martinez. The anti-Jewish campaign that he launched in 1378 intensified when he was made archbishop in 1390. Taking advantage of the death of Juan I on 4 June 1391, he fomented a riot culminating in the destruction of the judería in Seville. Many Jews were forced to convert to save their lives. The violence spread from one judería to another across Andalusia and Castile. The most flourishing Jewish quarters, in Toledo and Cordóba, were hit extremely hard. In July 1391 the wave reached Valencia, Majorca, Barcelona, and Gerona, wiping out Jewish life there.

These massacres greatly altered the Jewish community. A new figure appeared, the converso (convert). The conversos‘ motives and hopes were highly diverse. Those forced to convert continued to practice Judaism in secret; these were the crypto-Jews, or Marranos. Others used the opportunity to become full participants in Christian society and gain access to positions closed to Jews. Still others sincerely wished to become Christians, even if their baptism was forced upon them. The disputation at Tortosa in 1413-14, when Zerahia Halevi and Joseph Albo debated with the Christian convert Jeronimo de Santa Fé (José Halorqui) on the usual themes of Jewish-Christian polemic, was perhaps the last attempt to persuade the Jews by means of reason.

Christian society was uncertain as to what attitude it should take toward the Jews and conversos. The decision was made to separate the Jews and converts in order to ensure that the latter became good and sincere Christians and to prevent them from returning to Judaism. This was the mission entrusted to the Inquisition in 1480. Thomas Torquemada, who was appointed Grand Inquisitor, turned this into a redoubtably effective institution, relentlessly tracking down both “sympathisers” of Judaism and conversos, in Spain and Latin America, dragging them before tribunals, sentencing them to death in autos-da-fé, or condemning them in other ways.

After the conquest of Granada, Isabella of Castile and Fernando of Aragón signed the expulsion decree of 31 March 1492. This set out to resolve the thorny question posed by the Jewish presence by either conversion or exile.

The decree of expulsion

“Considering that every day it is manifest and patent that the aforesaid Jews continue to pursue their maleficent and pernicious objectives where they live and communicate with Christians, and so that in the future the faithful should be spared all opportunity to offend our holy faith, whom God has thus far kept from this sin, as should those who have committed it but have mended their ways and have come back to our Holy Mother Church: and this could easily happen because of the weakness of our human nature and the malignity of the power of the demon, who is constantly assailing us, unless we do away with the main cause of this peril, that is to say unless we banish the Jews from our kingdoms.”

In spite of pressure from Abraham Senior and Isaac Abravanel, two ministers of the Catholic monarchs, the Jews left their Spanish homeland on the ninth day of the month of Av, the date of the destruction of the Temple in Jerusalem. Abraham Senior agreed to convert while Isaac Abravanel joined others on the paths of exile to North Africa, the Ottoman Empire, Portugal, and elsewhere in Europe (Italy, France, England, the Netherlands). This was the Sephardic diaspora, which retained its customs and languages, Castilian and Catalan. The number who went into exile is hard to determine. Some 70,000 to 100,000 preferred exile to baptism -between a third and a half of Spain’s Jewish population at the time.

By the seventeenth century, they were no Jews left in Spain (except those in the tiny enclave on the African coast, where their interpreting skills were essentials to the survival of the garrison; they were not expelled until 1699). The Inquisition watched over the conversos with all its notorious severity.

Resistance

Some, like Isaac (Fernando) Cardoso, managed to escape the Inquisition. Born in Portugal in 1604, he was a doctor at the court of Philip IV. A respected intellectual, he knew all the great figures of the age, including Lope de Vega, and was treated by them as one of their own. The son of forced conversos, Cardoso lived ostensibly as a Christian and covertly as a Jew. In 1648, at the height of his fame, he suddenly left Spain and took refuge in Italy. There he publicly professed his Judaism in Venice and Verona and, under the name Isaac Cardoso, published one of the finest Jewish apologias, Las Excelencias de los hebreos.

The memory of Spain’s Jewish presence did not completely vanished, however. Count Duque Olivares had the idea of re-creating a Jewish community in Madrid in order to stimulate Spanish economic development. He must have known about the lucrative activity of the community in Amsterdam, which still spoke Spanish. However, he was forced to abandon his plans. In the eighteenth century, a few thinkers became aware of the losses occasioned by the departure of the Jews, arguing that they represented an important part of the Spanish heritage. Joseph Rodriguez de Castro, for example, published an essay on Spanish writers and rabbis from the eleventh century onward. King Charles VI also thought of bringing Dutch Jews to Spain and canceling the expulsion edict. But the Inquisition remained vigilant. The Holy Office was not abolished until 1813, during the War of Independence and the Liberal movement at the Cortes in Cadiz. Although reestablished during the Restoration, it was abrogated for good in 1834.

In the nineteenth century Jewish merchants came to northern Spain for the textile trade. They were of Spanish and Portuguese origin but had French nationality and were based in Bordeaux or Bayonne. These were isolated cases, however, and never led to the creation of organised communities. This century was also marked by war in Africa and the occupation of Tétouan between 1859 and 1862. In 1858 Ceuta, one of the Spanish enclaves in Morocco, was attacked by Moroccan Montagnards. Spain demanded reparation from the sultan, which was slow in coming. Queen Isabella then sent an expedition commanded by Prim and O’Donnell. The Spanish troops occupied Tétouan, where they were met by a population speaking a mixture of Arabic and Hebrew.

These were the descendants of the Jews expelled in 1492, who had almost miraculously kept going in that little town ever since. Until 1862, the occupation allowed the Jewish population to participate in the management of the town and to rise in society. It is appropriate to consider this a reunion of Spain and its Jews, for the event was made known to the general public by the newspapers and numerous accounts given by officers, and historians and philologists were fascinated to discover their language as it had been spoken four centuries earlier.

A visit by King Alfonso XIII to Seville in 1904 highlighted the existence of a small Jewish community there, most from North Africa. They welcomed the king to their street (Calle de la Feria) with a banner in Hebrew and Spanish. In the early 1900’s, Doctor Angel Pulido (1852-1932) who, when traveling along the Danube came across eastern European Jews speaking an archaic Spanish, launched several press campaigns and petitions to persuade Spain to recognise the communities in Serbia, Bulgaria, Romania, and Turkey, whose customs were still close to those of the Sepharad. He published two important works on the recent history of the Spanish Jews: Los Israelitas Españoles y el idioma castellano (1904) and Españoles sin patria, y la raza sefardi (1905). Pulido obtained authorisation to open a synagogue in Madrid (1917) for about 150 families and one in Barcelona (1914) for 250 people. He also created the Hispano-Hebrea Association in 1910 and in 1913 invited Professor Abraham Shalom Yehuda to teach Hebrew at the University in Madrid.

In 1914, the Zionist leader Max Nordau was forced to leave France because of his Austrian nationality. He came to Spain. King Alfonso XIII personally interceded with the kaiser to moderate the persecution and violence against the Jews in Palestine. After World War I, this process of rapprochement with the Jews gained momentum as major political figures such as the count of Romanones, Melquiades Alvarez, Alejandro Lerroux, Juan de la Cierva, Niceto Alcalà Zamora, and several army generals publicly supported this effort of recognition.

After the 1923 Treaty of Lausanne had created a legal void around certain protected Jews by putting an end to the system of capitulations in the Ottoman Empire, the Spanish government under General Primo de Rivera published the decree of 24 December 1924, which granted Spanish nationality to Sephardim who met certain conditions. Although this decree was little used during the six-year period of its validity, it would prove highly useful during World War II.

Under the Second Republic (1931-36), whose constitution guaranteed religious liberty and affirmed the secular character of the state, Spain aroused considerable interest among Jews in Europe and the Orient, who saw this guarantees as tantamount to an abrogation of the expulsion decree. In 1935, the lavish celebrations in Córdoba for the 800th anniversary of the birth of the doctor and philosopher Maimonides were like a public demonstration of Spain’s renewed interest in its Jewish past.

During the civil war, the communities of Seville and Ceuta and Tétouan in Morocco had to pay heavy taxes to support the nationalist troops of General Franco. Nazi influence revived anti-Semitic propaganda. Some 7,000 to 10,000 Jews from Europe, America, and Palestine came to fight in the international brigades, and even produced their own little Yiddish newsletter. At the end of the war, the victory of Franco’s troops was followed by the closing of the synagogues in Madrid and Barcelona. Marriages and circumcisions were prohibited and Jewish cemeteries were closed. Jewish children were compelled to attend Catholic school.

During World War II, neutral Spain became the only refuge in southern Europe from the lightning advance of the Nazi troops. Initially, transit visas were fairly easy to obtain. After the armistice of 1940, however, Spain and France took measures to regulate requests, especially through the Spanish consulate in Marseille. After July 1942, it was illegal for Jews to leave France, and so the crossings were made in secret, albeit with a degree of Spanish sympathy. Nevertheless, there were arrests, and a camp was established at Miranda de Ebro, where prisoners received psychological and material help from American Jewish organisations based in Madrid. These prisoners were gradually evacuated, most of them to Lisbon and the United States.

Spain still had to deal with the problem of the Jews in eastern Europe (Romania, Greece, Bulgaria, and Hungary) and France who were of Spanish origin or who, by virtue of the decree of 1924, has Spanish nationality. Jews in these areas called on Spain to help and protect them when their own governments abandoned them to the Nazis. Thanks to the actions of several Spanish ambassadors and consuls who knew about the faith of the deportees and put pressure on their minister in Madrid, notably Sebastian Romero, Julio Palencia, Romera Radigales, Bernardo Rolland, and Angel Briz, individual visas were issued, allowing several thousand people to escape. In some cases, in France and Greece, the property of these Spanish Jews was protected by the consular authorities and then returned after the war.

Although not favorable to the Jews, the policy of Franco and his ministers was not anti-Semitic. For Franco’s authorities, the Sephardic Jews were living testimony to a glittering period of their country’s history. Still, given Spain’s position of pro-German neutrality, political prudence and consideration of the balance of power between the Allies and the Axis were vital.

In 1941, the government paradoxically decided to set up the Instituto Arias Montano, which, with its journal Sefarad, became one of the most renowned centres for the study of Spanish Judaism and its diaspora. In 1949 a small synagogue opened discreetly in a Madrid apartment. The same happened in Barcelona in 1952. Although Catholicism was now the state religion, these small communities were tolerated. In 1967 a synagogue was built in Madrid, the first one since 1492. In 1978, Spain’s new constitution guaranteed religious freedom to all citizens. Today there are some 12,000 Jews in Spain, with communities established in Madrid, Barcelona, Valencia, Seville, Malaga, and the Moroccan enclaves of Ceuta and Melilla.

Jewish craftsmen and merchants settled in Switzerland’s Roman cities between the third and fourth centuries, but the first documents that mention them date only from the thirteenth century. Throughout the following two centuries, Jews were regularly accused of ritualistic crimes on Christian children and poisoning wells. They were expelled from the cities during the period 1384-1491. Certain families, however, benefited from the tolerance of local authorities.

Communities began to reform only in the early nineteenth century on the initiative of Alsatian Jews. The Jews of Switzerland were among the last in Europe to gain political equality, under foreign pressure in 1866. A popular vote in 1893 forbade ritualistic slaughter in Switzerland. This ban is still in effect, and kosher meat must be imported.

Switzerland supposedly neutral stance during the Second World War gave rise to an immense debate in 1995: substantial historical research showed that the Swiss government had adopted an anti-semitic asylum policy during the war, driving back thousands of refugees by requiring that Germany issue a “J” stamp on the passports of its Jewish nationals. Swiss banks finally admitted having wrongfully confiscated accounts belonging to victims of the Shoah, while insurance companies were accused of failing to pay premiums to the appropriate parties after the war.

This profound reevaluation of Swiss history, previously shrouded in the myth of neutrality, resistance, and humanitarian intervention, gave rise to a strong tide of anti-Semitism, stirred up by declarations from high political officials relayed in the media. Used to a low profile, Switzerland’s small Jewish community (18,000 people) suddenly found itself on the front lines, squeezed between the demands of Jewish organisations and the reluctance of Swiss institutions. Several years of dialogue will be needed for anti-Semitism to abate in Switzerland.

Why am I Jewish?

Edmond Fleg, whose real name was Fleigheimer, was a novelist, poet, and thinker born in Geneva in 1874. Until his death in 1963, he fought for the Jewish cause within the context of the Jewish Scouts of France, the Universal Jewish Alliance, and the Judeo-Christian Friendship.

“I am Jewish because wherever suffering weeps, the Jew weeps.

I am Jewish because whenever despair cries out, the Jew hopes.

I am Jewish, because the word of Israel is the oldest and the newest.

I am Jewish because the promise of Israel is a universal promise”.

Edmond Fleg, Why I Am Jewish, Paris, Les Belles Lettres, 1995.

At the end of the nineteenth century, an international conference took place sponsored by the Zionist Organisation that was dedicated to the problem of the future national language of the Jewish state. A heated debate was held and the question put to vote: Hebrew won out only by several votes over German to become the national language. As absurd as it might seem, the language of Goethe nearly became the official spoken tongue of Israel.

Between the end of the nineteenth century and the present day, there is a distinct “before” and “after”, a period the Jews call Shoah and the German the Holocaust. Why was this tragedy conceived, organised, and put into action in Germany of all places? The very country known for its level of civilised culture, fatherland of poets and thinkers?

Land of refuge for Jews

Between 1870 and 1914, Germany served as a refuge (France had come under suspicion because of the Dreyfus Affair) for a considerable number of Jews expelled from Russia, Poland, and Ukraine by the miserable conditions and pogroms that regularly bloodied the shtetlach. Born in Russia in 1885, Nahum Goldmann, the founding father of the World Jewish Congress, came to Frankfurt am Main at the age of five. He explained in his memoirs that it was natural for him, a Jew and Zionist, to enter into the services of the propaganda machine of Kaiser Wilhem II.

At the time he thought, “The great power of anti-semitism was in the hands of czarist Russia, and the victory of Germany seemed to me a good thing for the emancipation of Jews oppressed in the east in Poland, Lithuania, and other territories arbitrarily forced to submit to Russian governance”. A half century later the same Nahum Goldmann would negotiate with Konrad Adenauer the sum of reparations to be paid to the survivors of Hitler’s genocide and to the new state of Israel by a Germany in ruins after the war.

The synagogue of Worms in the Palatinate alone can serve as a symbol of the history of Germany and its Jews. Founded in 1034, the synagogue of Worms is one of the oldest in Europe. It was built by the same architects and craftsmen as the Romanesque cathedral of the city. Seven times destroyed and rebuilt, it was dynamited and razed during the violence of Kristallnacht on 9 November 1938, unleashing the anti-semitic violence of Hitler’s regime. Reconstructed after the war, it now serves as a place of worship for Jewish soldiers from the neighbouring American military base because there are no longer enough Jews in Worms to make up a minyan.

Origin and legends

According to certain tales, the Jewish presence in Worms dates back to the first destruction of the Temple of Jerusalem in 587 B.C.E. and the Jews’ refusal to respond to the call of the prophet Ezra to return to their land at the end of the Babylonian exile. Other stories suggest the first Jews landed on the banks of the Rhine with Marcellinus, a Roman officer who participated in the conquest of Jerusalem in 70 C.E. Hence, in the Middle Ages the Duisberg family simultaneously claimed to have directly descended from Marcellinus and demanded from the city the right to protect Jews and thus enjoy the comfortable revenues this privilege garnered.

Alternating tolerance and persecution

As in all of Christian Europe, the Jews of Germany have known alternating periods of tolerance and more or less harmonious existence with Christians (tolerance most often in periods of relative economic prosperity) and oppression, persecution, and expulsion. Yet the Jews had always seen this country as the Ashkenazi, or the Promised Land (Genesis 10), from which comes the general name for Jews of Central and Eastern Europe, Ashkenazim.

The arrival of the first Jews in Germany was made the subject of several legendary tales. Leo Trepp, the honorary rabbi of Mainz and the author of A History of the German Jews, notes with sagacity that “certainly, legend can not replace history, but history should not be in total contradiction with legend, lest history itself be rejected. Insofar as we are concerned, it means that we firmly believe in the settling of Jews in Germany dating back to ancient times.”

Jewish presence since the Roman Empire

The first written mention of a Jewish presence in present-day Germany is contained in a edict signed by Emperor Constantine dating from 321 C.E. that requests the Jews of Cologne (Colonia Agrippina) to send “two or three members” of their community to the city’s curia (government). This was not really the privilege that it might seem to be: the magistrates were responsible for Roman tax collection and often had to pay the emperor themselves when the populace was too poor or rebellious to be taxed.

This edict indicates that by this period the community of Rhenish Jews had acquired a certain economic comfort. This situation continued after the fall of the Roman Empire. The new masters of the country, the lords and bishops coming from the Germanic tribes, maintained cordial relations with the Jews. But there was some tension, since the papacy saw in Judaism a rival with Christianity. The Emperor, claiming the heritage of his Roman predecessors, saw himself as the protector of the Jews and the guarantor of a prosperity from which he could take his share. This situation irritated a portion of the clergy. Agobard, bishop of Lyon in the ninth century, complained bitterly that the Jews in his diocese has acquired too much influence under imperial protection: the nobles more often sought the blessings of the rabbis than the bishop, and Jewish merchants had succeeded in moving the weekly market from Saturday to Sunday.

Development of Speyer, Mainz and Worms

In the cities, Jews increasingly confronted hostility from Christian artisans’ guilds. Excluded from membership in most guilds, Jews devoted themselves to commerce and trade, notably with the Muslim Orient, taking advantage of their relations with Jewish communities settled in those regions. The scarcity of currency in the west and the ban on Christian lending money with interest pushed Jews towards this activity.

In the course of the ninth century, the prosperous Jewish communities of Speyer, Mainz, and Worms maintained excellent relations with the local (notably ecclesiastical) authorities. For example, in 1096, the archbishop of Speyer invited Jews persecuted elsewhere to settle in his city because their presence, he affirmed, “considerably increases the prestige of the city.” The religious and cultural life of these communities flourished: numerous synagogues were erected, “sages” such as Gershom ben Yehuda and Salomon ben Isaac, known as Rashi, moved there to give teachings on religion and law that still have authority today.

The beginning of the Crusades in 1096 and the gradual hardening of the Church toward the Jews during the Third and Fourth Lateran Councils (1179 and 1215) finally put an end to peaceful coexistence. In the wake of the first Crusades, non-Christians encountered on the way were put to the sword by bands of religious fanatics, landless peasants, and adventurers en route to Jerusalem.

Despite the warnings given by Jews in France who had already experienced murderous assaults from these armed bands, notably in Rouen, the leaders of the Rhenish communities thought the protection of the princes and bishops constituted a sufficient deterrent. This was indeed the case in Speyer, where the Jews and the troops of Bishop Johannes I succeeded in pushing back the assailants. In contrast, the authorities and townspeople of Worms and Mainz did nothing to stop the massacres.

Flourishing yiddish

Pursued or contained in ghettos as a result of increasingly severe discriminatory practices imposed by the Pope, the German Jews generally did not escape the destinies of fellow Jews meted out by Christians in the rest of Europe. At regular intervals in history, accusations that Jews performed ritual murders provoked pogroms and expulsions that conveniently settled outstanding debts owed to Jewish lenders. These persecutions drove numerous German Jews east toward Poland, where the sovereigns were more kindly disposed toward them and likely to welcome Jews in order to take advantage of their skills as merchants and bankers. Thus Yiddish, a mixture of Middle High German dialect and Hebrew syntax, was preserved in eastern Europe until these communities disappeared, victims of the Shoah.

The annals of Jewish history from the Roman Empire to the Wars of Religion reveal periods of relative tolerance alternating with episodes of extreme anti-Jewish violence. On the whole tolerance for the Jewish faith was scattered and disparate, occurring wherever a local prince declared himself “protector of the Jews” out of what was essentially self-interest. These periods of calm were preferred, however, to the acts of violence that sometimes broke out.

Martin Luther’s mission

In 1298, for example, 140 Jewish communities in Franconia and Saxony were annihilated in the space of six months by the hordes under the command of Chevalier Rindfleisch. Led my Martin Luther, the Reformation provoked upheaval in the Holy Roman Empire that did nothing to improve the well-being of the Jews there. Luther had first hoped to convert them by treating them with kindness and understanding. He thus protested in 1523 against the unfair treatment inflicted on them and noted that, “if the Apostles, who were Jews themselves, had behaved this way toward other pagans, not a single one among them would have become Christians.” Twenty years later, profoundly disappointed with the minimal impact he had in converting the Jews to the reformed faith, Luther gave free rein to his anti-Jewish hatred.

With regard to Jews and their lies: the Reformation and the Jews

In this infamous writing, Luther suggests a policy of “though love” toward the Jews: “burn their school and synagogues…, destroy their homes and make them understand that, like the Gypsies, they are not in their own land…, destroy all their books, [forbid] their rabbis to preach their heresies, so that we follow the sensible example of other nations like France, Spain, and Bohemia, which have always excluded Jews from their territories.” For four centuries theses imprecations justified popular anti-Semitism in Germany, despite efforts by numerous Protestant theologians and pastors to distance themselves from this interpretation of the great reformer’s text.

In this precarious situation, the Jewish communities of Germany owed their survival to the presence and ability of “courtly Jews” whom German princes, ever lacking in funds, needed in order to maintain their standards of living or to finance military campaigns. It was this in this capacity that Samuel Oppenheimer gathered the means necessary to defend Vienna against the Turks, and how Joseph Süsskind Oppenheimer (1692-1738), known as “the Jewish Süss”, became the chief adviser of Duke Charles Alexander of Wüttemberg. The favor of princes permitted Jews of the courts to obtain dispensations for their fellow believers, privileges often quickly reconsidered as soon as dynastic succession was at issue. At the end of the seventeenth century, the Jews living in the Hapsburg Empire numbered approximately 60 000 of a total of 40 million inhabitants. The largest Jewish community, with a population of 3000, was in Frankfurt.

Emancipation and Haskalah

The process that granted German Jews citizenship and enabled them to leave the ghettos was a long one, begun at the end of the seventeenth century and reaching its apogee after 1871, under Wilhelm I. The dawning of the Aufklärung, the German equivalent of the French Enlightenment, contributed to the secularisation of the Jewish community. Despite the restrictions of Jews’ civil rights in effect in the majority of German states, under Frederick Wilhelm I, and especially Frederick the Great (Frederick II), Prussia welcomed rich Jewish families banished from Austria in the same way that it had opened its doors to the French Huguenots ejected from their country after the revocation of the Edict of Nantes.

Moses Mendelssohn (1729-86) emerged in Berlin as a great figure in German Judaism. The founder of Haskalah, a contemporary method of of practicing the faith, Mendelssohn helped the Jews leave both the literal and spiritual confinement of the ghettos. Ignoring the criticism of Orthodox rabbis, he translated the Torah into German and encouraged Jews to use this language in their intellectual exchanges with scholars of other religions in order to dissipate misunderstandings of Judaism in caricatures and in Judeo-phobic polemics. This current of thought opened the way to the massive secularisation of German Jews, often manifesting itself as conversion to Christianity, the “admission ticket” required for entry into the ruling class.

The victory of the armies of the French Republic, and then the Napoleonic Empire, brought the Jews of Germany the legal emancipation established in France by the laws of 1791 and 1807. In a vanquished Prussia, Chancellor Hardenberg, busy preparing his revenge, thought it an opportune moment to rally the Jews to his cause by granting them full citizenship in 1812. In return, the vast majority of German Jews made a show of their patriotism in the exalted Wars of Liberation of 1813-15.

Heine and Marx, two Jewish converts from the Rhineland

Heinrich Heine (1797-1856), born in Düsseldorf, and Karl Marx, born in Trier, are the two most famous representatives of the wave of more or less sincere conversion to Christianity among members of the Jewish bourgeoisie for whom baptism constituted the “admission ticket” into high society. Their respective attitudes toward the religion of their forefathers are, however, completely opposite. For Heine, conversion changed nothing. The great German poet originally explained this in French, noting, “One doesn’t change religions. One leaves one of them that one no longer has for another that one will never have. I am baptised, but I am not converted”. In contrast Marx, baptised at the age of six, declared: “the earthly foundation of Judaism which conditions the Jews’ life here on earth is egotism. His religion is merely a lip service, and his god money”.

The childhood homes of Heine in Düsseldorf and Marx in Trier have been turned into museums.

Intellectual and economical development

Despite the persistent anti-Semitism across all strata of society, the Jews persisted in their undivided loyalty toward their German homeland until it became evident that, with Hitler’s rise to power, the Jewish-German symbiosis was destined to come to a tragic end. In 1871, Germany counted 512 153 Jews among its citizens (1,25 % of the population); in 1933 they numbered a similar 502 773 (0,76 % of the population) and represented the third largest Jewish community in Europe after Poland and Russia.

Their economic, intellectual, and cultural influence on German society was relative to their demographic presence. Figuring in the ranks of legendary businessmen are great bankers such as the Rothschilds, the Warburgs, the Bleichröders, and others, industrialists like the chemist Heinrich Caro, cofounder of IGFarben, and weapons contractors such as Alfred Ballin, president of HAPAG, the most important maritime company in Germany. German Jews are among the founders of department stores (Hermann Tietze, Wertheim) that have left their mark on retail and whose signs are still to be found in German cities. Likewise, many significant contributions to the sciences and culture were made by celebrated Jews: Albert Einstein, Robert Oppenheimer, Hermann Cohen, Hannah Arendt, Alfred Döblin, Lion Feuchtwanger, Arnold Schönberg, Max Reinhardt, Fritz Lang, Billy Wilder -among many others who came from the cultural world of German Jews, a spirit that lives on in many other places, brought there by those who could escape Hitler’s extermination plans.

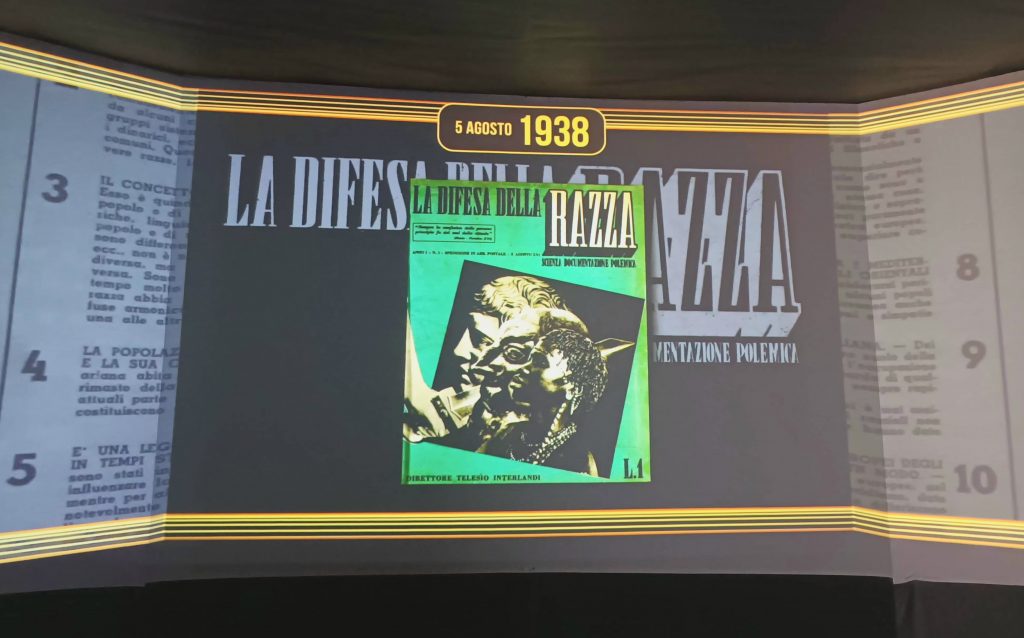

1938, a year of devastation

1 January: Jews are excluded from the Red Cross.

25 July: Jewish doctors are no longer allowed to practice medicine.

17 August: Jews are required to add the name “Israel” or “Sara” to their official papers.

27 September: Jewish lawyers are labeled “forbidden professionals”.

8 October: Jewish passports are required to be stamped with the letter “J”.

9 and 10 October: Kristallnacht. At the instigation of the Gestapo, armed bands plunder and damage Jewish synagogues, institutions, and shops.

15 November: Jewish children are excluded from public schools.

3 December: Jews are forbidden to go to cinemas, theatres, museums, and sporting events; drivers’ licenses belonging to Jews are cancelled.

8 December: Jews are excluded from universities.

Contemporary evolution

Today, the Jewish community in Germany numbers some 100 000 members. For many years this population has comprised Jews who survived the concentration camps and had nowhere else to go, or Jews who fled into exile but returned to Germany out of nostalgia. With the arrival of Jews from the former Communist countries in the last decade of the twentieth century, however, the population has abruptly grown. In welcoming them, the new and reunified Germany wishes to demonstrate that the country assumes full responsibility for its history.

The same concern pushed the country’s authorities to preserve what remained of the Jewish heritage after the destruction wrought by the Nazis. In that regard, Germany is paradoxically the European country where one finds the largest number of Jewish memorials, safeguarded at the initiative of officials in the larger cities and thanks to the action of persons or associations that have wrestled with the tendency to forget the Jewish heritage in towns and villages. The scope of the present guide does not permit an exhaustive listing of these sites. In general, municipalities with tourist information offices will willingly furnish all the information necessary to visit them.

On November 9, 2021, to mark the 83rd anniversary of Kristallnacht, 18 German and Austrian municipalities projected images of destroyed synagogues onto the walls of the buildings located there today. The virtual reconstruction of these synagogues was carried out by the Jewish Central Council of Germany, in partnership with the World Jewish Congress. This initiative was undertaken with the aim of passing on the history and geography of the synagogues to future generations who are less familiar with these painful pages of the past. German President Frank-Walter Steinmeier recalled in a speech the consequences of the night of November 9, 1938, when the Nazis murdered 91 people and destroyed 1400 synagogues.

The history of the Belgian Jews is similar to that of the Jews of western Europe generally, involving migrations and internal changes as the old communities came under the influence of other traditions.

The Jews came to what is now Belgium in the thirteenth century, settling at Arlon (Aarlen), Brussels, Hasselt, Jodoigne (Geldenaken), Zootleeuw (Leau), Leuven (Louvain), Mechelen (Malines), Sint-Truiden (Saint-Trond), and Tienen (Tirlemont). A Jewish tombstone from 1255 found in Tienen bears a Hebrew text mentioning the name Rebecca. It is now exhibited at the Musée royal d’art et d’histoire du cinquantenaire.

From 1348 to 1350, the Black Death swept through western Europe; the Jews were accused of poisoning fountains and, as a result, were persecuted. In the sixteenth century, a new era began.

Portuguese and Spanish Marranos arrived in Antwerp and made a major contribution to the town’s prosperity. Charles V ordered the expulsion of the “new Christians” on several occasions but was opposed by the town.

By the eighteenth century, the Jews were engaged in economic activities very different from those of their brothers in eastern Europe. They put themselves at the service of the monarchy, went into trade, and thus made an important contribution to economic development.

In 1808, the 800-odd Belgian Jews were integrated into the Israelite consistory of Créfeld, recognised by the French state. In 1831, after long negotiations with the new Parliament, an independent Israelite consistory was set up in Brussels, Belgium’s capital, which welcomed the growing migrant population from Eastern Europe.

In 1914, at the beginning of World War I, the Jews of Antwerp sought refuge over the border in the Netherlands, which remained neutral until the armistice in 1918. They congregated in Amsterdam, the Hague and Scheveningen. Many Jews from the Netherlands also went to live in Antwerp, which was also a major port and shared similar financial activities, such as the diamond industry.

In 1939, a large part of the Antwerp Jewish population fled to Cuba. This country allowed Jews from Antwerp to enter for a while in order to set up diamond factories. Some returned years later; others went on to the United States. On the eve of World War II, Belgium’s Jewish population was estimated at around 80,000. Some 25490 Jews and 353 Roma were deported to Auschwitz from the Dossin barracks in Mechelen, between the years 1942-1944. Only around 1000 came back.

Today, the Jewish population of 40,000 lives mainly in Brussels and Antwerp (but also in Liège and Charleroi). Their political and religious positions, as well as professional activities, divide up geographically.

Antwerp is constituted of Jews who are mostly religious or traditionalists. They have been prominent in the diamond industry from the beginning of the 20th century until the beginning of the 21st. Whereas Brussels’s Jewish community is mostly secular and has been active in the garment industry.

Holland has always welcomed political and religious refugees. The first great wave of Jews immigrated to the Netherlands from Spain and Portugal at the end of the sixteenth century.

Although nominally present since the twelfth century, the Jews in Holland were able to openly practice their religion for the first time beginning in this later period. The Sephardic Jews were the first to make a mark on Holland. In the turbulent context of the Dutch struggle for independence from Spain, they preferred to identify themselves as Portuguese rather than Spanish, even when they had immigrated from Castile or Andalusia. The Spaniards were attempting to impose their Catholic faith on the Calvinist Dutch as well as their centralised system of government and unpopular taxes, and so given their common distrust of Hapsburg Spain, the provinces of the Low Countries constituted an unexpected refuge for the Jews.

The first nucleus of a Jewish community arose on the banks of the Amstel River. It would take some fifteen years for this community to be recognised, since the Jews used Dutch names for managing their commercial affairs until 1616. Little by little they openly declared their identity, practiced circumcision, and reconnected to a Jewish tradition that a segment of the community did not even know. Although tolerated in Holland, Jews could not yet hold a civil or military office, nor could they become Christians or proselytise. Guild membership and engaging in retail trade were likewise prohibited, but not a single Jewish ghetto existed.

The first synagogue was constructed in Amsterdam in 1612. In 1619, a law stipulated that each city of the United Provinces was free to determine its own policies regarding the Jews, but that the towns could under no circumstances require Jews to bear any distinguishing sign. In 1657, Holland officially recognised Jews as citizens of the country.

The Dutch authorities asked them not only to declare their religion but also to behave as “good Jews”, in other words, to practice in an orthodox manner. This demand, applied equally to various Protestant sects, went beyond the promise of religious freedom, and left a majority of the exiles perplexed. The Jews of Portuguese descent, having largely modified their rituals and had to summon rabbis from other countries for help. The first among these was a Spanish-speaking rabbi from Thessaloniki.

This situation gave significant power to the leaders of Jewish religious communities, who then issued strict regulations. These leaders (parnassim) were responsible to the Dutch authorities for maintaining order within their groups. To be a member of the Jewish community in good standing, it was necessary to pay a tax and comply with its rules. The community founded its first synagogue, created educational and charitable institutions, and even established a trade tribunal for settling disputes between Jews. Among the first students at one of Amsterdam’s early Talmudic schools was a young boy of five years old who later became the famous philosopher Baruch Spinoza. Because of the magistrates of Amsterdam recognised only religious communities, not belonging to such a group risked serious trouble. A failure to obey Jewish law brought the threat of excommunication (herem), which not only isolated the individual but also threw him into a legal no-man’s-land. Those who were excommunicated were forbidden even to speak to family members. Records show cases of herem, which lasted anywhere from a day to eleven years.

A herem for life

A lifelong herem was pronounced only on two occasions, notably on 1656 against Baruch Spinoza. This descendant of Portuguese converts was banned from the community for having doubted the value of biblical writings. His views knit together notions of the immortality of the soul, the supernatural, the existence of miracles, and the possibility of a God outside philosophy. According to this disciple of Descartes, religion was entirely invented by mankind in order to impose a moral order upon society and to obtain obedience.

Beginning in 1635 Jews from eastern Europe began settling in Holland, first from Germany and then, after 1648, from Poland and Lithuania. In general, the immigrants arrived impoverished and were forced to live in slums. By the middle of the seventeenth century, however, 20% of the stockbrokers registered with the Amsterdam Stock Exchange were Jewish. They had recognized expertise owing largely to their knowledge of languages and connections developed during their Diaspora experiences. These same qualities permitted Jews to act as intermediaries in diplomatic affairs. Jews held visible positions in the silk industry, sugar refineries, and diamond cutting, as well as becoming printers, librarians (primarily of religious books), and doctors. They also pursued careers in banking and commerce. Some of these became successful in commerce with the Antilles and Dutch East Indies to the point of owning a quarter of the shares in the Dutch East India Company. by the mid-eighteenth century, Amsterdam possessed the largest Jewish community in Europe.

Ashkenazim versus Sephardim

As new arrivals, the ashkenazim were initially shunned by Sephardic society to the point that it was even forbidden to give them alms at the entrance of the synagogue. Intermarriage between the two communities was not permitted, nor was the burial of Ashkenazim in the Ouderkerk (Old Church) cemetery (located in the suburbs of Amsterdam). Unable to find better employment, the Ashkenazim were relegated to domestic labor for the Sephardim. At the time, the word tudesca (literally “German woman”) was synonymous with “household servant”. Later the wealthier Polish-Lithuanians would adopt the sae elitist attitude and attempt to get rid of the poor among them… In 1674, the Ashkenazim joined the Sephardim community in large numbers for the first time. Of a total population of 180,000 Jewish inhabitants in Amsterdam, the Sephardic community numbered around 2,500 members. The Ashkenazim had become the clear majority, with the Sephardim representing only 10% of Amsterdam’s Jewish population (down to 6% at the beginning of the twentieth century).

With the French Revolution and the creation of the Batavian Republic in 1796, the National Assembly granted civil rights to the 23,400 Jews in Holland. The Netherlands was the first country to accept Jews in Parliament and to grant them access to government posts. Napoleon Bonaparte’s occupation of Holland led to the promulgation of an agreement regulating relations between “German” and “Portuguese” Jews, and to the establishment of a mutual organisation under the direction of a Jewish assembly.

King William I (1815-40) likewise advanced the welfare and education of the Jewish community. In 1857, Jews were permitted to attend public schools and obliged to reserve religious education for Sundays and evenings. Jewish schools were reopened in Amsterdam only in the twentieth century.

The first half of the twentieth century was marked by an increasing number of mixed marriages and thus a decline in the traditional structure of the Jewish community. The new captains of industry, such as Samuel Van den Bergh, whose margarine factory gave birth to the giant Unilever, or those who headed the large department stores chains were perfectly integrated into non-Jewish society. Jewish newspapers (four weeklies and numerous monthly newspapers and magazines) are still in existence from before the outbreak of the Second World War, but from that period on have been published in Dutch.

In May 1940 German troops occupied the Netherlands. The Jews of Holland suffered greatly under Nazi domination: Of a total population of 140,000, 104,000 were killed. A Dutch minority actively opposed to the Nazis helped 22,000 Jews into hiding. Sadly 8,000 of those Jews were caught. After the war, between 20,000 and 30,000 Jews resettled in their Dutch homeland.

At the dawn of the new millennium, Jews numbered around 27,000 of a total population in the Netherlands of 15.5 million inhabitants. Of the hundred synagogues that existed before World War II, some thirty remain. Regular services take place in only a few of the surviving synagogues.

While Ireland is not an obvious destination for those interested in Jewish culture, the island does offer a few surprises. Ireland’s Jewish population has never been higher than 8 000, and that was in the late 1940s. Today, it is down to under 2 000, of which 1 500 are in the Republic of Ireland. The last kosher butcher closed shop in May 2001.

The first trace of a Jewish presence is found in the Annals of Innisfallen, which relates the arrival of five Jews, probably from Rouen, in Limerick harbor. But it was not until 1290, and the expulsion of the Jews from England, that a real community took shape.

The expulsion of the Jews from the Iberian Peninsula in the fifteenth century sent a second wave of emigrants to Irish shores, mainly the southern coast.

A century later, in 1656 or 1660, depending on the source, a group of Marranos opened the first prayer hall, opposite Dublin Castle. The cemetery at Ballybough (County Dublin) has allowed Jewish burials since the beginning of the eighteenth century.

Between the end of the Napoleonic Wars and the start of the twentieth century, pogrom drove Jews to Ireland from Central Europe, especially Lithuania.

Some of those who did not continue on to the Americas settled in Irish towns, built synagogues, opened kosher butcher shops, and created close-knit communities. The most important of them was located around Dublin’s South Circular Road.

Jews also became prominent in public life. Those from czarist Russia played a leading part in the establishment of the Tailors’ Union in 1909. Jews were involved in the independence movement, which triumphed in 1921.

Robert Briscoe is the best remembered of these: a colorful figure and, as he claimed, the only Jewish member of the IRA. He was twice mayor of Dublin, in 1956-57 and 1961-62. His son Benjamin occupied the same position in 1988-89.

Another memorable name is that of the Herzog family. After occupying the highest religious positions in Ireland, Rabbi Isaac Herzog became the first chief rabbi of the fledgling state of Israel. His son Chaim, who was born in Belfast and raised in Dublin, became the sixth president of the Jewish state. Today, the Dublin rabbinate’s offices are still at Herzog House, on Zion Road.

If Scottish Jews did not suffer the same fate as English Jews with the expulsion of 1290, it is mainly because there were hardly any Jews before that date in the country. Administrative documents make it possible to note the presence of Jews in Edinburgh at the end of the 17th century.

Edinburgh, then Glasgow, were the first Scottish Jewish communities. Mainly through access to universities, when students obtained the right at the end of the 18th century to study there. These students then settled permanently in the cities.

The first synagogue was built in Glasgow in 1823. It was moved into an apartment on a transitional basis. At the end of the 19th century, the Garneth Hill Synagogue was built.

The arrival of Jews from Eastern Europe during the pogroms unfolding in their homelands favored Glasgow more than Edinburgh. The latter was known at the time by the representative of the Jewish community, Salis Daiches, who came from a long line of rabbis from Lithuania. He united the community and was its spokesperson in the complicated period of the interwar years. The synagogue built in 1932 on Salisbury Road was created in his homage.

In 1971, the presence of 15,000 Scottish Jews was recorded. The vast majority lived in Glasgow (13,400 people) and the rest in Edinburgh (1,400), Dundee (84), Ayr (68), Aberdeen (40) and Inverness (12). Forty years later, the number of Scottish Jews fell drastically: 5,887, which is less than one percent of the population. Of these, 4,224 lived in Glasgow, 763 in Edinburgh, 30 in Aberdeen and 22 in Dundee.

There is no historical record of organised Jewish communities in the British Isles before the Norman invasion of 1066, when King William encouraged Jews -mainly merchants and craftsmen- to follow him. Those who did came mainly from France (Rouen) but also from Germany, Italy and Spain. They settled in London, York, Bristol and Canterbury. Well regarded by the Norman kings, the Jews’ main role was financial; as moneylenders, they kept the kingdom’s finances, and the heavy taxes they paid represented a not inconsiderable source of revenue.

The difficult situation of Jews in the Middle Age

Anti-Semitic feelings first surfaced in 1144, when Jews were accused of making human sacrifices, and culminated with the massacre at York in 1190. A new stage was reached when Jews were forced to wear a distinctive yellow sign in 1217.

The trend eventually led to the decree of expulsion by Edward I in 1290. But if England was the first country to expel the Jews, they were never completely absent. In London, a domus conversorum, or “house of converted Jews”, standing on the site of today’s Chancery Lane Library, was home to Jews, mostly Marranos, who continued to practice their religion in secret.

Their return under Cromwell

Foundations for a real return were laid after 1649 under Cromwell’s Commonwealth as a result of intercession by Menasseh ben Israel, a rabbi of Portuguese origin living in the community at Amsterdam. The period of William the Orange (1650-1702) saw the arrival of numerous descendants of Jews who had been expelled from Spain and Portugal by the Catholic Monarchs, Ferdinand and Isabelle, in 1492. At the end of the seventeenth century, Judaism was made legal by the Act of Suppressing Blasphemy. One of the results of this legalization was the construction of the Bevis Marks Synagogue in London. A jewel of the city’s Jewish heritage, the building is still in use today.

From 1750, most new immigrants came from Central Europe, and they tended to settle further to the north than their predecessors, attracted by the burgeoning cotton and wool industries in Birmingham, Manchester and Liverpool. A new wave of Jewish immigrants reached the shores of the British Isles after 1881, driven this time by Russian anti-Semitism. By 1882, there were 46,000 Jews living in England.

Development of the community during the 19th century

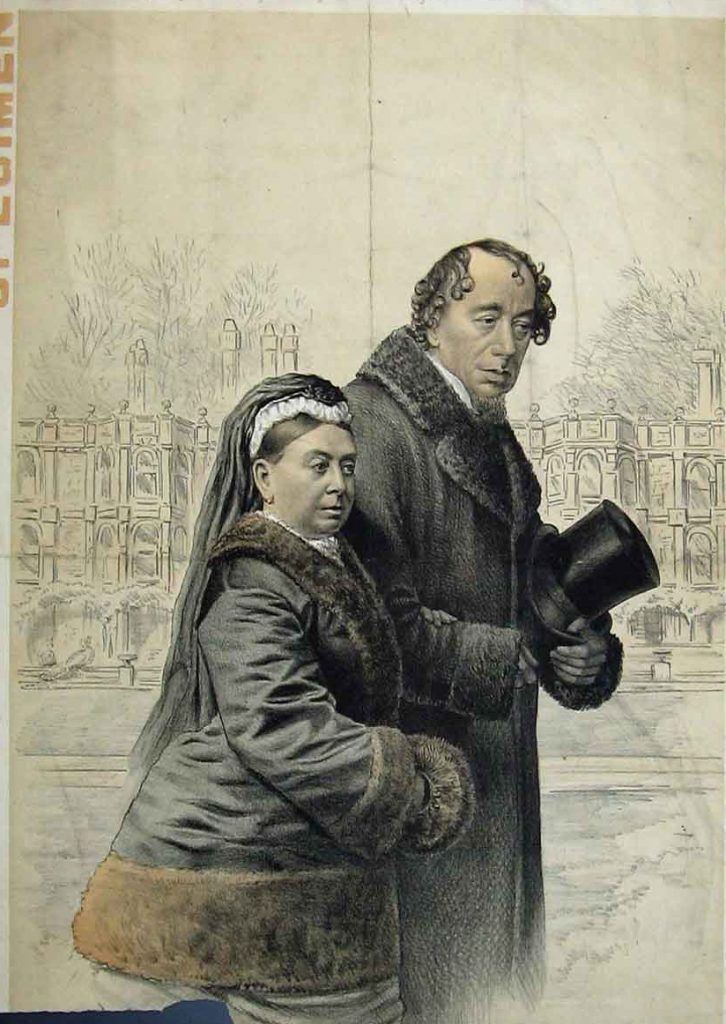

This presence is highlighted by the figure of Moses Motefiore (1784-1885), who was knighted by Queen Victoria in the first year of her reign; the launch in 1841 of the Jewish Chronicle, which remains one of the more lively Jewish newspapers even today; and, above all, the career of Benjamin Disraeli, who twice held the position of prime minister (1868, 1874-1880). From such evidence, we can conclude that by 1890, Jewish emancipation in the United Kingdom was complete. Certainly, this would explain the strong attraction of the country for immigrants. There were no fewer than 120,000 new arrivals between 1880 and 1914, and, on the eve of World War I, the community numbered over 250,000.

One result of the First World War, was a new anti-Semitic feeling, which led to a marked slowdown in immigration. Immigration, however, resurged in the 1930s with the arrival of some 100,000 German and Central European Jews, who brought economic and cultural knowledge.

The British government declared itself favorable to “the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people” (Balfour Declaration, 2 November 1917). Placed under British mandate in 1922, Palestine suffered frequent clashes between the autochthonous and Jewish populations. In an effort to saveguard good relations with the Arab states, the British government published a white paper limiting Jewish immigration into Palestine to 15,000 persons a year for the five years from its promulgation. This was in May 1939, just as Nazism was beginning to threaten all of Europe. The situation was further complicated in 1945 when the survivors of Nazism were stopped on their way to the Promised Land and kept in camps on Cyprus-British camps, this time. In Great Britain itself, which escaped occupation by the Axis powers, deportations were virtually non-existent.

The Jewish community in Britain reached its apogee in the late 1960s, when the population exceeded 400,000. Today there are only 350,000 with two-thirds living in London; nonetheless, this represents one of the world’s biggest Jewish communities.