Strasbourg, the regional capital, is also home to the European Parliament, as witnessed by the European flags welcoming you at the train station. This magnificent city, at the heart of many political, national and religious conflicts over the centuries, has become a symbol of political, national and religious reconciliation and cooperation. Crossing its many bridges to the magnificent architectural imprints of the centuries and the cultural and gastronomic activities on offer await you…

Jewish history is constantly present here. Is it not said that the rue de la Nuée-Bleue owes its name to the cloud that preceded the Jews expelled from the city in 1349, and that the rue Brûlée evokes the Jews burned alive that same year for refusing baptism?

The Jewish presence in Strasbourg has been attested to since the 12th century and, according to some researchers, is even older. The community had a synagogue, a mikveh and a cemetery. On Valentine’s Day, February 14, 1349, the Jewish population of Strasbourg was massacred. The few Jews who had fled in time were gradually allowed to return to Strasbourg, mainly as a result of an ordinance of 1375. But their banishment was promulgated in 1389. It remained in force until the French Revolution. During all these centuries, they had the right to stay for work, but had to pay an entrance tax. They lived in villages in the region that were more welcoming. At the beginning of the 17th century, the Jewish population of Alsace began to grow. At the end of the century, the rabbinate of the Jews of Alsace was created.

On the eve of the Revolution, some Jews managed to make timid progress towards the emancipation of their people. But the one who made the greatest impression was undoubtedly Hirtz de Mendelsheim, better known as Cerf-Berr. A contractor for the King’s armies, he succeeded, not without difficulty, in obtaining the right to settle in Strasbourg in the 1770s. He fought hard for the emancipation of the Jews, succeeding in abolishing in 1784 the corporal toll imposed on the Jews. He also helped the city of Strasbourg to fight against famine.

From 19 to 25 May 1789, a delegation of 37 delegates met in Strasbourg to draw up a book of ‘grievances and wishes of the Jewish nation of Alsace’. Nevertheless, it was not until after the Revolution, in 1791, that Jews were officially allowed to settle in Strasbourg. The community began to form, with David Sinzheim, Cerf-Berr’s brother-in-law, as its first rabbi. The Grand Sanhedrin met on 9 February 1807, presided over by David Sinzheim, who was later appointed Chief Rabbi of the Central Consistory of France.

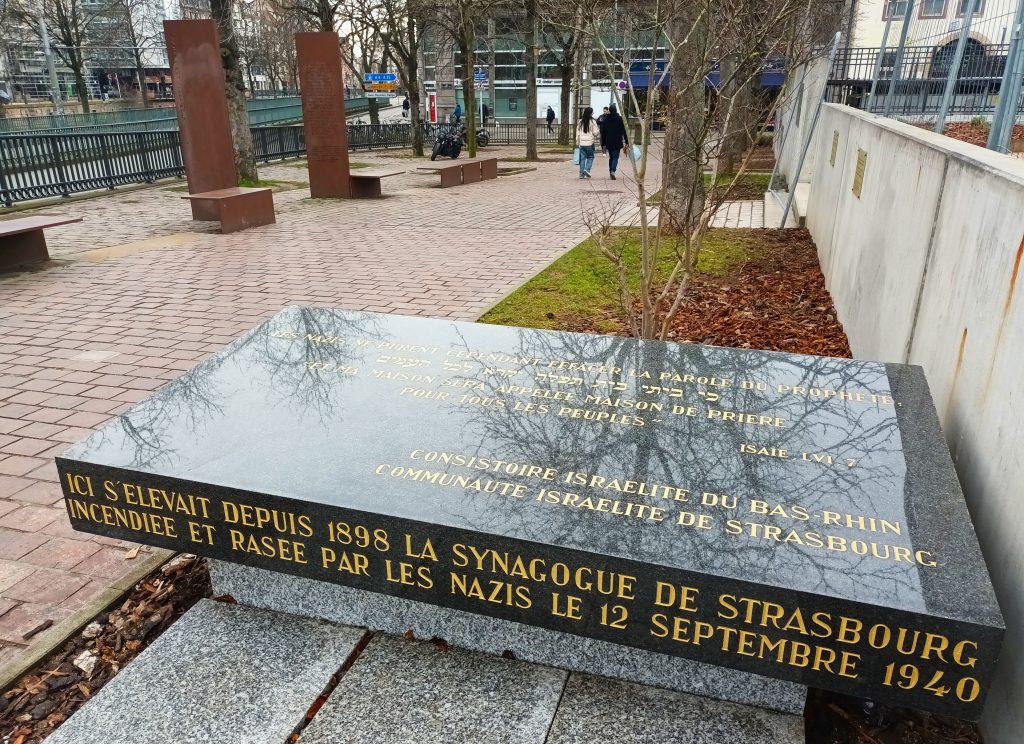

From 1811 to 1834, the congregation met in the former Poêle des Drapiers, then in a synagogue built in rue Sainte-Hélène in 1834. The rapid growth of the community necessitated the opening of a new synagogue on rue Sainte-Hélène. Built by the architect Ludwig Lévy, the Quai Kléber synagogue was inaugurated on 8 September 1898, replacing the previous Jewish places of worship.

On the eve of the Second World War, the city had 10,000 Jews in Strasbourg. Following the capitulation of France, they escaped to other regions, reconstituting their community, mainly in Périgueux and Limoges. René Hirschler, the Chief Rabbi of Strasbourg, ensured the link with the dispersed Jews of Strasbourg and undertook courageous work to save the prisoners who might be deported. Mobilization in the Resistance and to help the population was also done through associations such as the EEIF and the OSE. Many of these resistance fighters from Strasbourg died on the battlefield.

The monumental synagogue on the quai Kléber was burned down by the Nazis in 1940. One thousand Jews from Strasbourg were murdered during the Shoah. After the war, eight thousand Jews resettled in the city.

From 1950 to 1958, the city made a building in the former Arsenal available to the Jews of Strasbourg. The Synagogue de la Paix (Peace Synagogue) is located in the Neustadt district, with its impressive Prussian-style buildings, built between the 1880s and the First World War and enabling the city to triple in size. The synagogue was designed by the architect Claude-Meyer-Lévy and can accommodate 1,600 worshippers. Its main façade is decorated with a wave of Stars of David. On 13 March 1958, the Strasbourg community inaugurated this major new place of worship, in the presence of the Mayor of Strasbourg Charles Altorffer, the Minister of State Pierre Pfimlin, the Chief Rabbi of France Jacob Kaplan, Charles Ehrlich (President of the Community), Joseph Weill (President of the Consistoire) and Abraham Deutsch (Chief Rabbi of the Bas-Rhin). On 22 November 1964, General De Gaulle presided over ceremonies marking the 20th anniversary of the liberation of Strasbourg by General Leclerc’s troops. He visited a number of monuments, including Notre-Dame Cathedral and the Synagogue de la Paix. Simone Veil, a former deportee who became Minister of Health from 1974 to 1979, then First President of the European Parliament from 1979 to 1982, made a high-profile visit to the synagogue in 1988.

Inside, you’ll admire the holy arch, whose bold shapes highlight a tapestry by the artist Jean Lurçat. The site is actually home to five synagogues, including one following the Ashkenazi rite of the Rhine Valley and another combining Ashkenazi and Sephardic rites, sometimes during the same ceremony! The large René Hirschler hall is used for major celebrations.

The arrival of North African Jews in the 1960s, mainly from Algeria and Morocco and a few families from Tunisia, encouraged the transformation of the Léo Cohn village hall into an oratory, followed by the inauguration of the Rambam synagogue in the early 2000s.

In 1868, Oscar Berger-Levrault demolished the old buildings on the corner of rue des Juifs and rue des Charpentiers to build a new printing works. A mikveh dating from the first half of the 13th century was discovered at the time, but not preserved or even photographed. Much later, during renovation work in 1984 in the Rue des Juifs, it began to be preserved and inscribed in the city’s monuments list. The central element consists of a square room of 3 meters on each side made of gray sandstone topped with red bricks. In each corner, Romanesque corbels remain.

The Esplanade synagogue was inaugurated on 12 April 1992 in rue de Nicosie. At the time, it was located in an area marking the growth of the Jewish population a little further away from the city centre.

As confirmed by Alain Fontanel, the deputy mayor of Strasbourg, in 2018 to the Akadem website, following the death of Simone Veil, the city had wished to pay tribute to her. Thus, the Avenue de la Paix, was renamed Avenue de la Paix – Simone Veil. In order to honor her fights for women’s rights, European unity and the memory of the Shoah. A very strong nomination symbolically since this avenue was previously named the German street, then the Daladier street and during the occupation, the Hermann Goering street!

In 2019 was inaugurated the place Jean Kahn, located opposite the synagogue. This, in tribute to this great figure of French Judaism. A year earlier, the mikveh on rue des Charpentiers was reopened. A rare occurrence in France, the Jewish population of Strasbourg has increased in recent years, with the development of institutions and the diversification of currents, both Orthodox and liberal. In 2025, the Jewish population of Strasbourg represents about 20 000 persons.

In the Alsatian Museum a small country oratory is reconstituted with its library, its Torah scroll and its Shabbat lamp. Two other rooms are dedicated to Judaism. There are some curious pieces, such as a carved wooden Star of David with a double-headed imperial eagle from 1770.

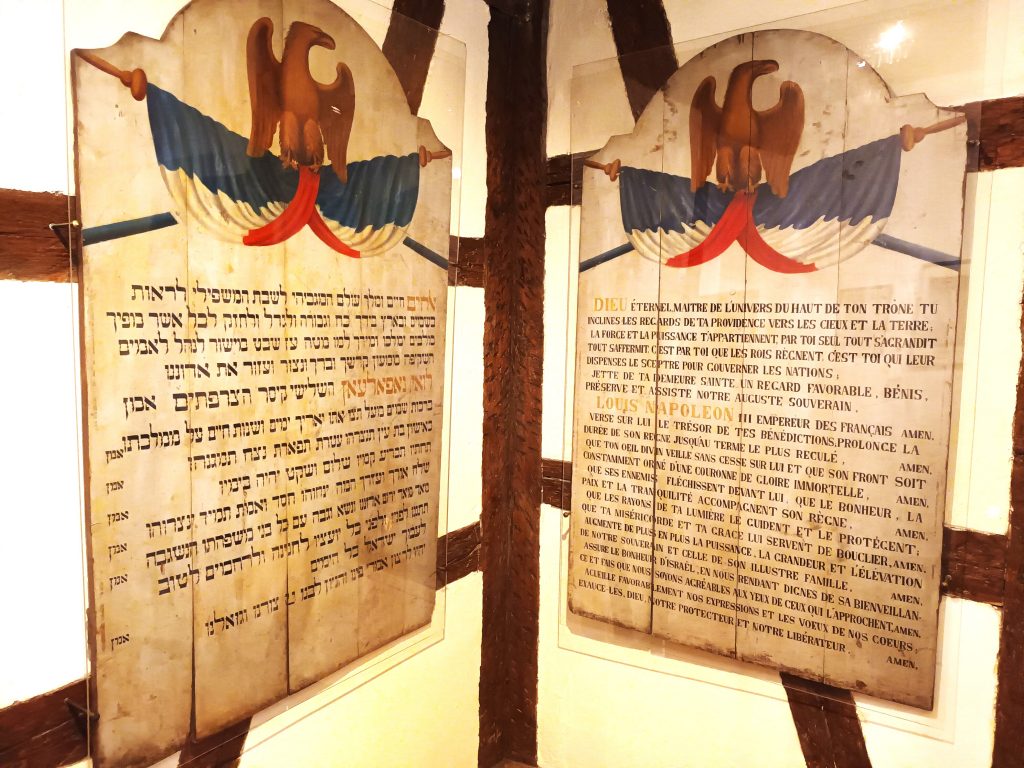

But also panels in Hebrew and French from the synagogue of Jungholtz calling for divine blessings on Emperor Napoleon III, and a painting commemorating the “Inauguration of a Pentateuch in Reichshoffen on November 7, 1857”, a moving evocation of fervor and patriotism.

In the courtyard of the Musée de l’Œuvre Notre-Dame dedicated to the arts of the Strasbourg region between the eleventh and seventeenth centuries, one can see Jewish funerary steles from the medieval cemetery that was located on the site of the current Place de la République.

On 23 January 2025, the AEPJ (European Association for the Preservation and Promotion of Jewish Culture and Heritage), which is responsible for the European Days of Jewish Culture, celebrated its 20th anniversary in Strasbourg. This is no coincidence, given the symbol of European reconciliation that Strasbourg represents, but also the crucial role played by local and Luxembourg personalities, notably Claude Bloch and François Moyse, in setting up AEPJ. The Council of Europe, under the auspices of the Luxembourg Presidency, hosted the event on 23 January, which was attended by Claude Bloch (Honorary President of the AEPJ) and François Moyse (President of the AEPJ), Björn Berge (Deputy Secretary General of the Council of Europe), Eric Thill (Minister of Culture of the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg), Catherine Trautmann (former Minister of Culture, former Mayor of Strasbourg and currently a municipal councillor), Gabrielle Rosner-Bloch (Regional councillor for culture and religion, in charge of heritage for the Grand Est Region) and Irena Guidikova (Head of the Department for Democratic Institutions and Freedoms).

Jguideeurope was delighted to take part in the day’s events, which included lectures on medieval Judaism in Alsace, Erfurt and the Iberian Peninsula. This was followed by visits to Strasbourg (in particular the Synagogue de la Paix) and a reception at the Residence of the Permanent Representation of Luxembourg. A day where speakers and participants recounted many moving personal stories and signs of hope for the future, such as the revival of Jewish culture in Poland. Above all, they repeatedly reaffirmed their commitment to the fight against anti-Semitism in all its forms, the preservation of cultural heritage and the sharing of humanist values between peoples. This is particularly important 80 years after the liberation of Auschwitz.

ITINERARY

This itinerary will enable you to discover the places mentioned in connection with Jewish life in Strasbourg, both past and present. It’s just under 4 km starting at the Strasbourg train station.

Take rue Kuhn and you’ll come to quai Kléber, where the former synagogue burnt down. Period photographs commemorate the site.

The site has been named Allée des Justes (Alley of the Righteous), in memory of the courageous people who saved Jews during the Shoah. It was inaugurated on 22 July 2012 by Roland Ries (Senator and Mayor of Strasbourg).

Follow the quay to the left, until you reach rue du Général de Castelnau and that of his colleague General Rapp.

Rue Sellénick and the surrounding area is a small shtetl with schools, cultural venues such as the Cédrat bookshop and kosher restaurants.

Just a couple of hundred metres down the rue Strauss Durkheim, you’ll come across the Synagogue de la Paix, next to which is the Place Jean Kahn.

The Avenue de la Paix Simone Veil was named in tribute to the first President of the European Parliament, whose appointment, and above all her commitment to women’s rights and remembrance, symbolises the will and reality of peace in Europe since the end of the Second World War.

The avenue leads to the beautiful Place de la République (where the ancient Jewish cemetery used to be), surrounded by the Palais du Rhin, the University Library and the National Theatre.

Next to the National Theatre, the Passerelle des Juifs (Footbridge of the Jews) leads to the Quai Lezay Marnesia.

Take the Rue du Parchemin, which continues into the Rue des Juifs and where you will discover the old mikveh. Visits to the mikveh, like those to the synagogue, should be organised in conjunction with Jewish institutions.

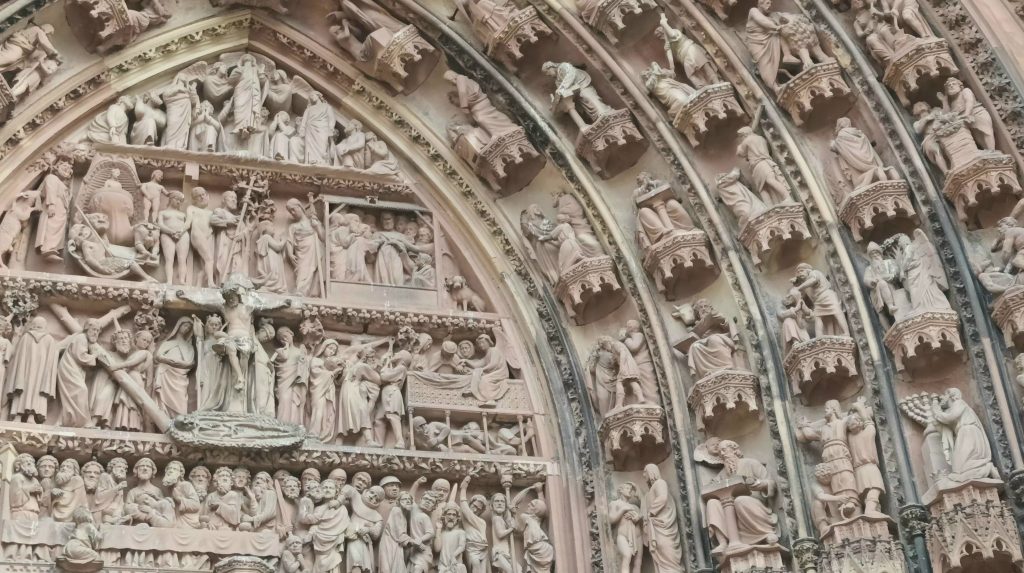

At the end of this street, opposite the former Kammerzell house, you will come across Strasbourg’s magnificent cathedral.

With its sculptures and its famous clock. A clock that, with all its references and inspirations, will take you on a journey through time and space.

She will also tell you that it’s time to round off this wonderful visit by visiting the Musée de l’œuvre-Notre-Dame, just down the road, and the Musée Alsacien (Alsatian Museum), a 5-minute walk away across the Pont du Corbeau.

This astonishing museum of regional arts and traditions lets you discover the diversity of this experience and its representations over the centuries. In particular, the ingenuity of the Alsatians in coping with the harsh winters and their early ecological awareness! There are also the various pieces of furniture made from fir wood, and the glassmakers of Meisenthal who invented Christmas decorations on fir trees, replacing the apples and walnuts usually used for this type of decoration when there were food shortages. Not forgetting local ceramics and the evolution of its iconic costumes.

Alsace’s ancient religious traditions are presented in rooms dedicated to Catholicism, Protestantism and Judaism.

But they are also presented at different times, as in Room 9, where the objects used for circumcision are on display.

Room 10 has a map showing the former presence of religions in Alsace. Then you enter the rooms dedicated specifically to each of the three religions. Many Jewish objects of worship are on display.

There is also a prayer board in Hebrew and French for Napoleon III.

And above all, as a link between the past and the future, the tribute to the Guardians of the Sites, the courageous people who fought to preserve Alsatian Jewish cultural heritage in the villages of the region, such as Habsheim, Hagenthal, Mommenheim, Muttersholtz, Westhoffen and Zellwiller, presented in this room. The Jewish oratory is located just beyond in room 15.

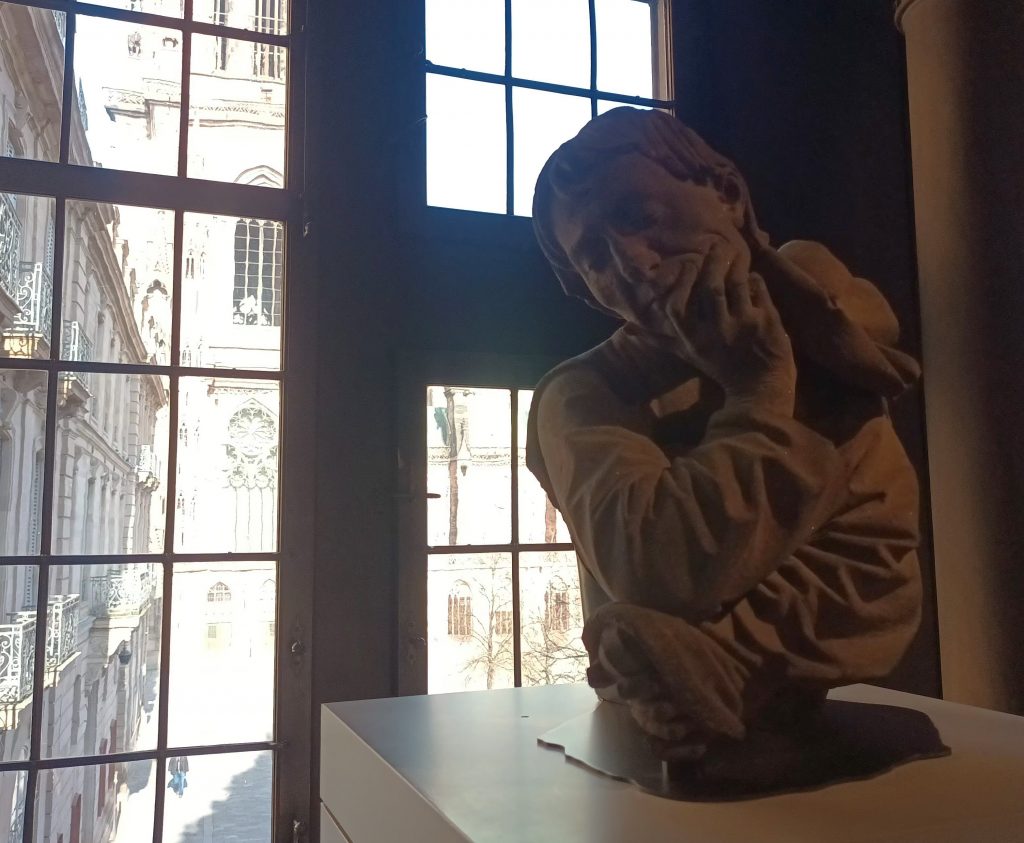

We had the pleasure and honor to visit the Museum of l’Oeuvre Notre-Dame with Jean-Pierre Lambert, President of the Society for the History of the Israelites of Alsace and Lorraine and one of the members of the Alsatian team behind the European Days of Jewish Culture and Heritage.

Jguideeurope: How was this museum created?

Jean-Pierre Lambert: The Foundation of l’Oeuvre Notre-Dame dates back to 1224, when it was responsible for the construction and restoration of Strasbourg’s cathedral. After the bishop had been defeated at Hausbergen and had definitively lost all temporal power over the city, since 1262 it has depended exclusively on the municipal authorities of the Free City of Strasbourg. The Foundation had its own sculpture workshops, as well as an architecture department and employed historians. In 1459, it became the Supreme Lodge of the Holy Roman Empire. Closer to home, it is the driving force behind a group of 18 cathedral workshops from 5 European countries, which will be included on UNESCO’s World Intangible Heritage List in 2020.

Since its creation, the charity has accumulated documents, replaced statues and other artefacts from the cathedral. It has also received countless donations and bequests from the faithful, religious art objects, not always related to the cathedral, such as forests or buildings. The OND conserves and exhibits all kinds of objects, most of them medieval: numerous Jewish tombstones from Strasbourg’s first cemetery, as well as statues, stained glass windows, paintings and tapestries from all over Alsace. To preserve and display the jewels in its collection, the OND has a magnificent complex of medieval and Renaissance houses opposite the cathedral, all of which have been added on top of each other, making for a highly original and interesting tour, passing through doorways and staircases that give a labyrinthine feel to this journey through time. Along the way, you can still admire the operative masons’ meeting room.

Some of the exhibits on display bear witness to the way in which Jews were viewed by the church, providing a better understanding of a complex relationship that is often caricatured to the extreme. It is also possible to do this research by visiting the cathedral, but it is more difficult because the evidence is less visible and the original statues and stained-glass windows have often been replaced by copies, or worst by 19th-century recreations of statues destroyed during the Revolution, which fortunately are less frequent than at Notre-Dame de Paris.

Was this view of the Jews positive or negative in the Middle Ages?

It was both. Exactly what we find in the Cathedral. It’s the same message, combining closeness and knowledge of the other with an often gentle but real demonisation.

Let’s take a few examples: in the first room of the OND, you can see a Romanesque capital where Jews with slightly deformed faces stand side by side with bats. This is a rare representation. For Francis Salet, the bat is the image of those who, like the Jews, are ignorant and refuse to see the truths of the Christian faith. This capital, which is in a rather poor state of repair, is probably a model (forgotten by its owner) of a similar capital carved in OND used during the restoration of the church at Sigolsheim. Some people have thought that these are two originals, and have deduced that this rare representation is common!

A little further on, a stained-glass window depicts Moses presenting Jews, recognisable by their pointed hats, with the bronze snake from Genesis coiled on a tau, resembling a caduceus. But we soon discover that the Jews are crossing their hands, in the manner of a praying Christian. This representation was very common in the Middle Ages and signifies that Moses, having seen the light, is himself asking the Jewish people to convert, which those present accept. According to Saint Paul, this conversion is the sine qua non for the return of the Messiah and therefore for the Parousia. For some, it had to be preceded by the return of the Jewish people to their homeland. This explains the unconditional support for Israel of American evangelical Protestants. The original statues of the Church and the Synagogue, perhaps the most famous medieval statues in the world, are also on display at the OND. To understand the scene, you need to go and see their copies, on the south portal of the cathedral. The synagogue, frail, very beautiful and swaying, is attracted to Christ and Solomon, his equal in wisdom and predecessor, but at the same time turns away from them. She is like the bride in the Song of Songs, willing and unwilling. Will Solomon be able to convince her? The fate of the world seems to depend on it.

Can you give us other examples of this complexity?

Yes, of course. Let’s take a scene that is very often depicted: the sacrifice of Isaac. For a Christian, this sacrifice is the first attempt to save the world by sacrificing a righteous person. It was a failure, because the sacrifice was unfulfilled. Christ had to die before humanity could be saved. I much prefer the Jewish interpretation, which says that by saving Isaac, the angel showed that the sacrifice of a human being is unacceptable.

A small stained-glass window, left over from a work by the great Pierre Hemmel d’Andlau (circa 1450), shows Jesus going to Limbo to pick up Moses and Elijah, who fold their hands as a sign of conversion. This well-known legend comes from an apocrypha. In one corner, a devil is discreetly depicted, along with an inferno. This work reminds us that the Sheol of the Jews, confused with limbo, was often interpreted as hell by Christians, especially in the Middle Ages.

I would like to end with two superb and comforting works. At the OND there is a marvellously sculpted ensemble representing the circumcision of Jesus. Everything is there, including the bottle of talcum powder. The circumciser has put on his glasses. His prayer shawl has become a kind of scarf, held by his two bent elbows: it won’t get in his way. The high priest has celebrated too much, and his face, a little heavy, is also too red.

In the cathedral, in the lower stained-glass windows on the south side, to the west, Jesus is being laid in the tomb by Joseph of Arimathea and Nicodemus, who are very focused. But both are wearing the large conical hat that identifies Jews, which is very rare (a similar representation exists in Fribourg, Switzerland). Jesus was born and died a Jew…

What are the oldest objects attesting to the Jewish presence in Strasbourg and Alsace?

In Strasbourg, of course, there’s the medieval mikveh, which is of impressive size, but also the tombstones on display at the OND and the Historical Museum. Rouffach is also home to France’s only fully preserved medieval synagogue (1290), which cannot be visited at present, and there are several inscriptions attesting to the presence of synagogues in Obernai, Molsheim and Haguenau. However, there are fewer traces of Jewish presence after the 16th century.

Are local authorities involved in sharing Strasbourg’s Jewish cultural heritage?

On the whole, yes. A number of institutions in Strasbourg offer Jewish tours, including the Tourist Office, another of the city’s tourist offices in which I played a part, the Departmental Tourist Development Agency and others. The mikveh has recently been restored, with a much more flexible access system. A memorial garden was created very recently on the site of the consistory synagogue, which was destroyed by the Nazis. This formalisation shows that the local political authorities clearly have the objective of better highlighting the Jewish presence in Strasbourg. This will cover not only the medieval period, but also the entire Jewish history of Alsace and Strasbourg, which has been largely uninterrupted from 1140 to the present day.

A joint research programme on Jewish heritage has been launched by the Regional Directorate for Cultural Action (DRAC) and the regional inventory service. The national education system, through the intermediary of the rector, is preparing a programme to highlight Judaism, which is necessary in these times, and Alsatian universities are currently attracting more students interested in Jewish history. It should also be noted that it was in Strasbourg in 1996, with the support of the Bas-Rhin department at the time, that the ‘Open Doors to Jewish Heritage’ operation was launched (in 1996, 5,000 participants in 15 locations in the Bas-Rhin), which over time became the ‘European Day of Jewish Culture and Heritage’ (in 2022, almost 150,000 visitors, 29 participating countries, 860 activities in Europe). Last but not least, plans are underway to list Alsace’s collection of synagogues, the most extensive in Europe, as a World Heritage Site…

You can continue your visit in a variety of ways, depending on what you fancy and what this beautiful city has to offer within a few hundred metres. In particular, the Place Gutenberg, named after the famous printer.

The museums of Fine Arts, Archaeology, the City of Strasbourg or the Palais Rohan. Shops, restaurants and seasonal attractions… or the simple pleasure of relaxing on a terrace on the banks of the River Ill or strolling through the historic district of Petite France

and over the Vauban Bridge, hesitating over which bank to return to and prolong the pleasure of being in Strasbourg.