The South is very different from the rest of the Italian peninsula because of the Jewish presence that was brutally interrupted by the expulsion of 1510, as this is reflected in the rather small archaeological heritage.

In Calabria, Jews did not live in the isolation of ghettos, but in their own neighborhoods, the “Giudecche”. Near Vibo Valentia (formerly Monteleone), on the splendid Tyrrhenian coast, you’ll find the Jewish quarter of Nicotera, one of the largest in Calabria, founded by Emperor Frederick II in 1211, which is well worth a visit. A little further on, on the hills, you can marvel at the “Giudecca” of the charming village called Arena, and not far away the “Giudecca” of Soriano Calabro, where craftsmen and especially Jewish dyers thrived and where you can find the traditional cakes with ancient Hebraic recipes, the “mostaccioli”, made from flour, honey and almonds.

The Orthodox Jewish community today does not exist as such in Calabria, as there are few practising Jews and a few dozen are on their way back or converting to Judaism. For this reason, Calabria depends on the community of Naples, but it is rich in Jewish history. However, a new breath of fresh air has come from the United States thanks to a progressive Jewish woman, Rabbi Barbara Aiello, an American-Calabrian, who is determined to contribute to the resurgence of the anusim, the descendants of the Jews of the south who were forced to convert at the beginning of the 16th century. In 2007 she created the Ner Tamid (Eternal Light) synagogue in Serrastretta (province of Catanzaro), with the aim of reviving this Calabrian Judaism that has existed for centuries in a latent state and that was just asking for it under the southern Italian sun.

Of all this Calabrian history, we recall that Shabbetay Donnolo, a famous physician and philosopher, operated in Rossano around the year 1000; that in Reggio Calabria, on 5 February 1475, Rashi’s commentary on the Pentateuch was printed, the first work in Hebrew with the date indicated. Moreover, the parents of the great Kabbalist Hayim Vital, known as “il Calabrese”, came from the region.

It is worth noting that the 4th century synagogue of Bova Marina, rich in mosaics, the oldest in the West after that of Ostia Antica, bears witness to a flourishing community. Archaeological evidence of the Jewish diaspora can also be seen at the National Archaeological Museum of Reggio Calabria, at the Antiquarium Leucopetra di Lazzaro, a hamlet in Motta San Giovanni, in Vibo Valentia, and at the National Archaeological Museum of Scolacium in Roccelletta di Borgia.

On the Ionian coast, in Monasterace marina, near Riace marina, where the two bronze giants were found, you can visit the Library of the Agafray Cultural Association, which was opened by the sister of Agazio Fraietta, an enthusiast of Jewish culture who has passed away, to raise awareness among Calabrians of their cultural heritage, particularly Hebraic. It features a library with a wealth of documents on the region’s past, as well as recreational activities relating to the region’s artistic activities.

Nowadays, in the province of Cosenza, there is Ferramonti, the remains of the concentration camp for foreign Jews, built during the last world war. On the Cedar Coast (between Tortora and Cetraro, concentrated around Santa Maria del Cedro), every year in August, rabbis from all over the world come to harvest the excellent Calabrian citrus fruits that are an integral part of the Sukkot celebrations.

In Cosenza, for the recurrence of the Jewish Festival of Lights, a majestic candelabra is publicly lit in Largo Antoniozzi, in the historic centre, near the old Jewish quarter. In addition, the Calabria Kosher Food Festival was inaugurated in 2019.

A curiosity: in Reggio Calabria, the tourist can walk along a beautiful street dedicated to Aschenez (great-grandson of Noah) who, according to a legend, founded this beautiful city that looks out over the Mediterranean.

Text written by Riccardo Guerrieri

Our interview with Lina Fraietta, about a wonderful project created in the town of Monasterace, a library enabling researchers and visitors to find out more about Calabria’s Jewish cultural heritage.

Jguideeurope: How did the library project come about?

Lina Fraietta: The Agafray Library is managed by the Agafray Cultural Association. The Association was born in memory of my brother, Agazio Flaviano Fraietta. Agazio, although he had no academic degrees, was a passionate scholar and researcher of Calabrian culture and the history of Jews in Calabria.

Over the past few years he had collected more than 2,500 books and objects both Calabrian and Jewish, which now constitute the library holdings of the Biblioteca Agafray, based in Monasterace, where Agazio was born.

A department dedicated to children and young people has been added, on my initiative, with books and the initiation of several creative workshops for children.

Since one of the objectives of the Library is to make the territory known, connected with the Library is a vacation house “Agafray house” in a nearby town: Sant’Andrea Apostolo dello Ionio. The house favors stays for members of the Association and for those who want to get to know Calabria.

Is it involved in any cultural or educational projects in the region?

The Library and Association place themselves at the service of citizens; several events have since been proposed and organized under the patronage of local institutions, especially the Municipality of Monasterace where the Library is located. It is currently not involved in specific school or regional projects.

What book on Calabrian Jewish heritage has particularly impressed you?

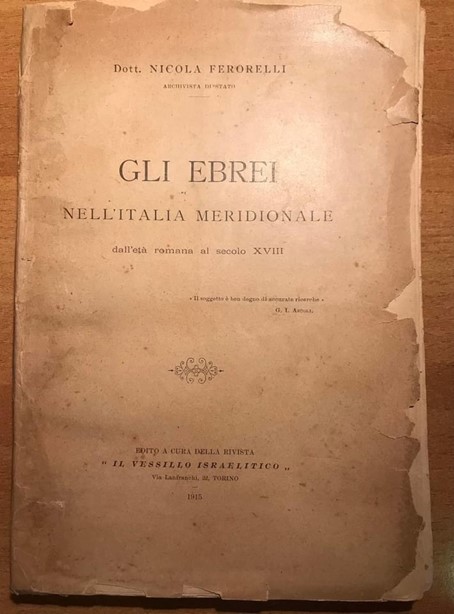

There are several books on Jewish heritage and in the possession of the Library that have impressed me, although few authors and researchers have dedicated themselves to this topic; I will mention one out of all: “Gli Ebrei nell’Italia Meridionale”, by Nicola Ferorelli, whose photo is reproduced here.