‘Apart from Versailles, I didn’t know you could talk about views’, declared Jean Gabin in the movie The Gentleman of Epsom. Versailles is indeed immortalised by its history, its kings and queens, its castle, its works of art and its gardens, as the busloads of tourists testify.

But the town to the south-west of Paris has also been home to a very active Jewish life since the end of the 19th century. A contemporary symbol of this vitality is the fact that the first French edition of Limmud was held in Versailles in 2006.

Although the Jewish presence in the region probably dates back to the Middle Ages, the Versailles community was mainly formed after 1870 when Alsatian Jews, like many other French people, rejected German domination and left Alsace to live in other regions and towns, including Versailles.

Many Jews from Versailles were murdered during the Holocaust. Their involvement in the Resistance was significant. Lola Wasserstrum, for example, distributed anti-Nazi leaflets around the Versailles barracks and was arrested on 31 August 1942. But also Charles Weil and Pierre Feist, fighters in the Black Mountain maquis.

Another famous Versailles Resistance fighter was Dr Paul Weil. Arrested with a group of Franc-Tireur fighters following the destruction of the PPF headquarters in Vichy, he survived deportation and resettled in Versailles after the war, where he continued to practise as a doctor. In 2004, the town council paid tribute to him by erecting a plaque in the vicinity of rue Champ Lagarde, Rond-point Paul Weil . A monument has also been erected in memory of the victims of the Shoah in the Jewish cemetery in Versailles.

It was not until the arrival of the repatriates from North Africa in the 1960s that the Jewish community was able to be reinvigorated, and today consists of several hundred families.

The synagogue

The first synagogue dates back to the Ancien Régime and was located at 9 avenue de Saint-Cloud in Versailles. A larger synagogue became necessary in the 19th century. In 1853, the synagogue opened a new place of worship in part of the former Hôtel du Duc de Richelieu, located next door at 36 avenue de Saint-Cloud.

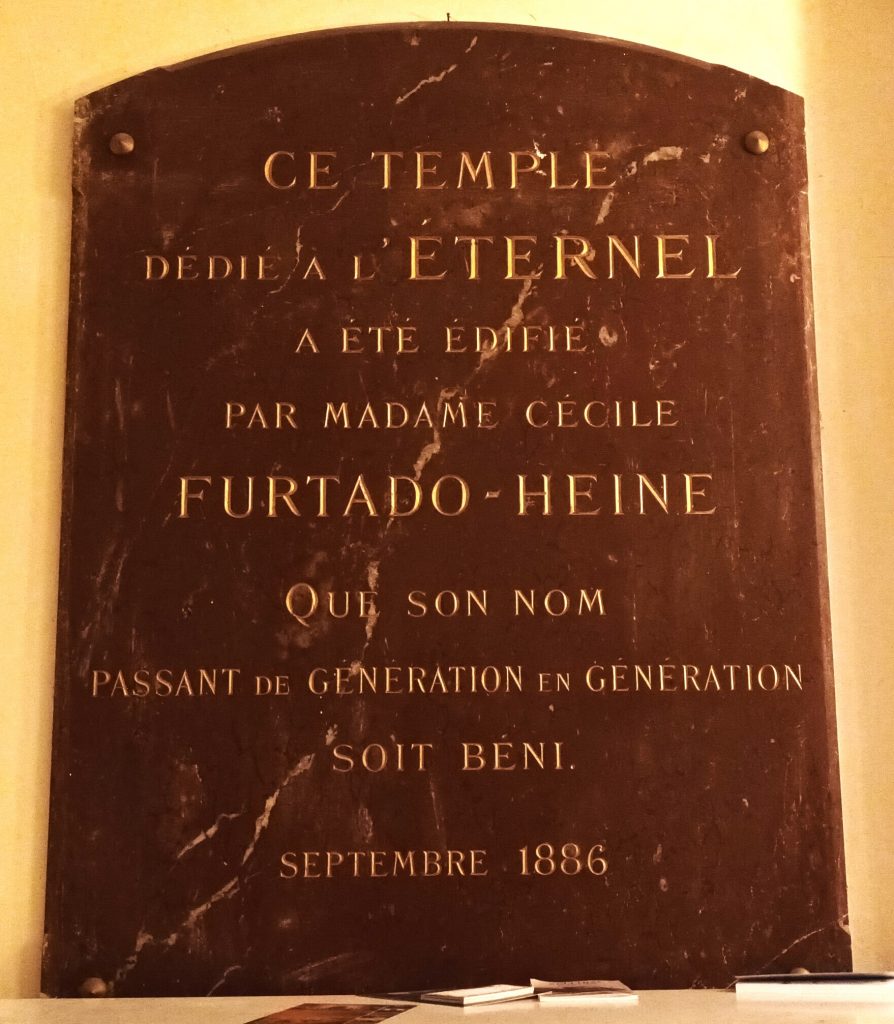

The building was becoming unhealthy and a request was made to the local authorities to build a new Israelite temple on rue Albert Joly. In 1883, thanks to funds provided by Cécile Furtado-Heine (1821-1896), the Israelite Consistory of Paris was able to buy land there. In a letter dated 9 December 1882. Madame Furtado-Heine confirmed her support to the community leader Maurice Cerf: ‘Mr President, I have the honour of informing you that I am placing 200,000 francs at your disposal to build an Israelite temple that I am offering to the Versailles community. I would like the temple to be built with two sacristies, one of which will be used for the usual service and the other as a school for the children. I also want a modest but suitable accommodation for the rabbi and another for the officiant…’.

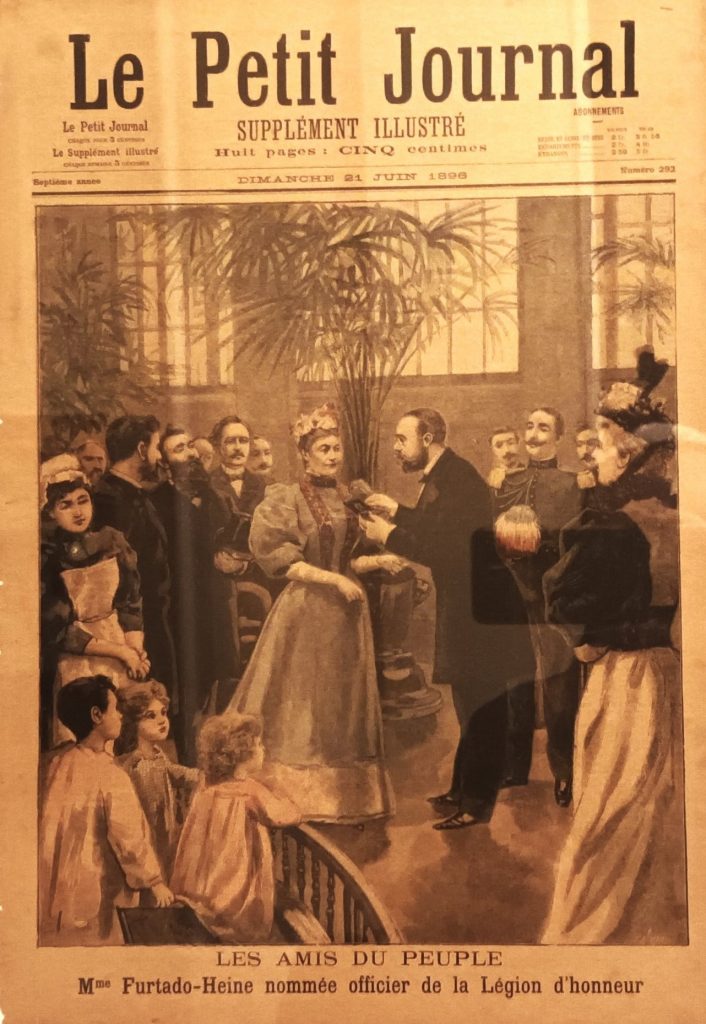

Cécile Furtado-Heine, along with Daniel Oziris Ifla, helped finance the synagogue on rue Buffault in Paris. She devoted much of her life to philanthropy. In particular, she organised ambulances during the 1870 war, set up a school for young blind people, a dispensary and a nursery in the 16th arrondissement, and a dispensary in Levallois. She also donated funds for a nursery school in Bayonne and gave her villa in Nice to the Ministry of War for conversion into a rest home for officers.

The design of the Versailles synagogue was entrusted to the architect Alfred Aldrophe, the most important Jewish architect of the time. He had also built the Victoire synagogue in Paris, the town hall in the 9th arrondissement and numerous public buildings, schools and orphanages. A man, but also an era that places the synagogue within similar constructions the Victoire, Tournelles and Buffault synagogues, their construction having begun under the Second Empire and completed under the Third Republic.

In 1886, on the occasion of the inauguration of the Versailles synagogue, Chief Rabbi Zadoc Kahn made the following statement: ‘In Versailles, alongside countless masterpieces, it is fitting that the Israelite faith should be able to display without shame the centre of its religious life’. The Versailles synagogue has a very special status, being attached to the Consistoire of France and not to the Consistoire of Paris, as are many synagogues in the suburbs of the capital.

The Versailles synagogue comprises two buildings. The central building contains the synagogue, an oratory for prayers on weekdays (dedicated to the memory of André Elkoubi, who officiated there from 1964 to 1975) and a reception room. Next door is a building with a flat and lounge. There is also an inner courtyard where classes are held, including Talmud Torah on Sundays.

The outside of the synagogue features stained glass windows and a rose window. At the top of the building is a sculpture of unfolded Bible scrolls.

The vestibule of the synagogue is a place of remembrance. Of its donor Cécile Furtado-Heine, but also of the members of the Jewish community who died for France during the First World War, as well as the victims of the Shoah. The vestibule also features a plaque and objects paying tribute to those who played an active part in the development of Jewish life in Versailles.

Inside, the white walls welcome the faithful. The tevah was salvaged from the original synagogue on avenue de Saint-Cloud. Dating from 1853, it is therefore older than the synagogue that houses it today. The tevah was originally imported from Portugal.

Around ten Sifreh Torah are kept in the aron hakodesh. The women pray on the first floor, where one can also see a beautiful organ, donated by the children of Léopold Taub. Dating from the late 19th century, it is used for wedding celebrations.

A special feature of the Versailles synagogue is that every 21 January, the day Louis XVI was executed, a prayer is said in his memory, to remind that he was a benefactor of the community.

Refurbishment work was carried out in 2006 to mark the synagogue’s 120th anniversary. On completion of the restoration work, a book was published by ACIV and designed by Sam Ouazan, Brigitte Levy, Colette Bismuth-Jarrassé and Dominique Jarrassé. With texts by Mayor Etienne Pinte, ACIV President Samuel Sandler, architect Dominique Lecuiller and historians Dominique Jarrassé and Gérard Nahon.

Contemporary Jewish life

Rabbi Arié Tolédano now heads the Versailles Jewish community, which is managed by ACIV, chaired by Maurice Elkaïm. The synagogue lives on donations from the faithful. Services are held here every Saturday morning, with a kiddush offered to participants afterwards.

When Shabbat finishes early on Saturday evenings, film screenings, concerts and other cultural activities are organised. Just over fifty people can attend in the reception room.

But when events need to accommodate more people, they are organised at the cultural centre in Le Chesnay. The same goes for bar mitzvoths and weddings. This centre can accommodate 200 people. The nearest kosher restaurants are in Boulogne, so it is advisable to contact ACIV, which endeavours to find solutions for tourists and students.

The Jewish cemetery at Versailles probably dates back to the time of Louis XVI. It is said that in 1788, while passing near the forest, the King of France came across some Jews burying their dead. Surprised, Louis XVI questioned those close to him. They told him that as Jews were not allowed to bury their own dead in the Versailles cemetery, that was how they managed. It was therefore Louis XVI who decided, following this coincidental encounter, to grant the Jewish community a plot of land measuring 3 perches, or approximately 102 m², located behind the Catholic cemetery of Notre-Dame, now rue des Missionnaires.

In 1821, Louis XVIII granted a plot of land for the current Jewish cemetery in Versailles, located on the Butte de Picardie. The cemetery is located on the Butte de Picardie, more precisely rue des Moulins, which today corresponds to rue du Général Pershing, at number 3. The former Jewish cemetery was taken over by the town after 1834.

A street named after Samuel Sandler was inaugurated on the 6th of November 2024, in Versailles, on the initiative of the mayor of Versailles, François de Mazières, and his municipal councillor Muriel Vaislic. The ceremony was attended by Samuel Sandler’s family and representatives of various faiths.

Samuel Sandler passed away in January 2024 at the age of 77. He worked tirelessly to preserve the memory of the victims of the 2012 Toulouse attacks, in which his son Jonathan Sandler and his grandsons Arié and Gabriel were murdered at the Otzar Hatorah school. Former president of the Consistory of Versailles and administrator of the Central Consistory, he was also an aeronautical engineer and co-authored Souviens-toi de nos enfants (Remember Our Children) (Grasset, 2018) with Emilie Lanez, in memory of those who perished.

Sources: Le Parisien, Times of Israel