The sculptures on the Saint Anne portal of Notre Dame Cathedral offer one of the most moving testimonies we have to medieval Judaism.

The frieze in question, just above the doorway, dates from the late twelfth century. It represents the Virgin’s mother, Saint Anne, meeting her future husband, Saint Joachim. The unknown artist used Parisian Jews as his models in order to represent these early Christians. The men have the long robes and pointed hats worn by Jews in medieval times.

The left-hand side illustrates Anne and Joachim’s wedding. Wrapped in his prayer shawl, the rabbi stands between the betrothed, whom he takes by the hand. All the details here evoke the atmosphere of a Parisian synagogue. The artist has painstakingly sculpted the arks, the eternal lamp, and the piles of books that are so characteristic of Jewish life.

The iconography in the center is purely Christian: an angel announces the coming birth of Mary to the barren couple.

On the right, Anne and Joachim are taking their offerings to the synagogue. On the altar is a Torah scroll. The end of the frieze depicts two Jews in conversation. These stone figures convey images of Judaism from ancient times.

On the two central buttresses on the main facade, notice the niche on the right housing The Vanquished Synagogue, an allegorical statue by Fromanger depicting the eyes covered by a snake, a broken scepter, and crown trodden underfoot.

The pendant statue on the left is The Church Triumphant by Geoffroy Dechaume. These sculptures were made during the restoration work undertaken by Viollet le Duc in the nineteenth century, replacing the original sculptures destroyed during the Revolution.

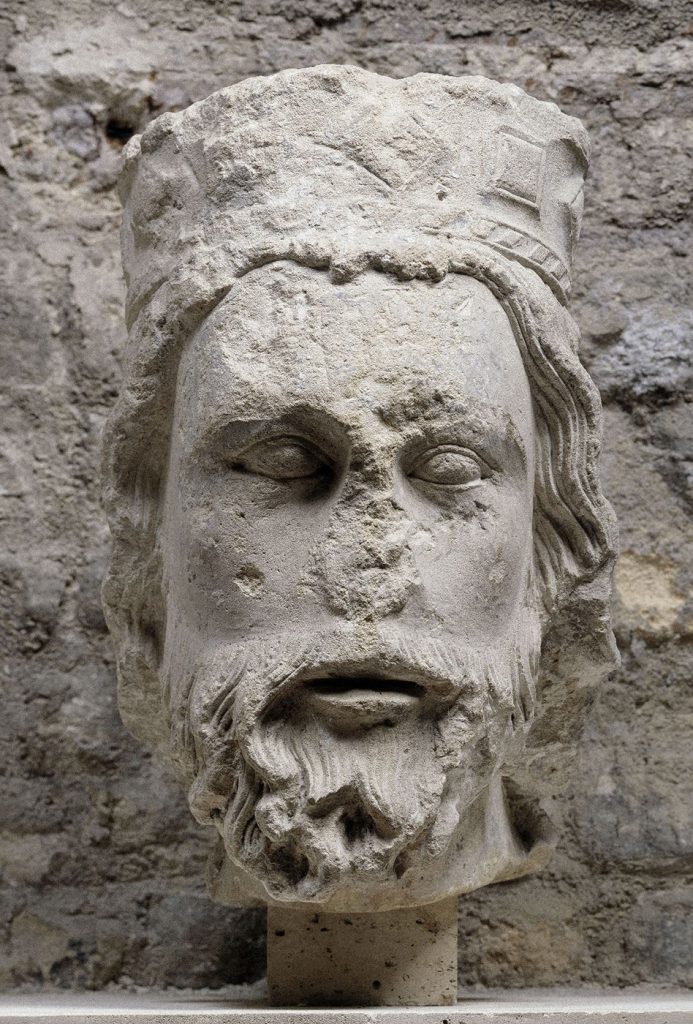

Just above them, the Gallery of Kings represents twenty-eight kings of Judah and Israel who, according to Christian tradition, were the ancestors of Jesus. In 1977, 364 fragments of sculptures from Notre Dame that had been smashed during the Revolution were found during work on rue de la Chaussée d’Antin. Although no traces of the Vanquished Synagogue were found, twenty one of the twenty eight heads of the kings of Judah and Israel were discovered. These are on display at the Cluny Museum (Musée national du Moyen Âge des Thermes de Cluny).

In 1849, during the construction of the Hachette bookstore at the corner of rue Pierre-Sarrazin and rue de la Huchette, now boulevard Saint-Michel, nearly eighty Jewish stelae were discovered, most of which were donated to the Musée de Cluny by Louis Hachette. Other stelae, located near the site of the future discovery and still visible in the 17th century, were transcribed by Étienne Baluze before their disappearance. This exceptional collection, now largely deposited in the Museum of Jewish Art and History, is the main material evidence of the large Jewish community established in Paris in the 12th and 13th centuries. Although it is known that there were two Jewish cemeteries in Paris in the 13th century (and a third, on the right bank, which was used at a later date, in the 14th century), only documentary traces remain of the second, which was closed in 1273.

The Jewish cemetery of the rue Pierre-Sarrazin extended over a significant part of the left bank, between the rue Pierre-Sarrazin, the rue Hautefeuille, the rue de la Harpe and the rue des Deux-Portes (the route of these last two streets corresponds to that of the present-day boulevards Saint-Michel and Saint-Germain). A few rare texts make it possible to follow its history, notably a document from 1283 mentioning a conflict with the college of Bayeux. As soon as the Jews were expelled by Philip the Fair in 1306, the cemetery was condemned to disappear: the land was given by the sovereign to the Dominican nuns of the Priorale Saint-Louis de Poissy. The plot of land was sold in 1321 to the Count of Forez and gradually subdivided. It is difficult to know when the cemetery began to be used, because of the number of fragmentary and undated slabs. It can only be noted that, apart from one stele whose dating is disputed, the oldest dated stele preserved is that of a man who died in 1235, which seems to indicate that the cemetery was only used for just over three-quarters of a century.

The Rue de la Juiverie, now incorporated into the Rue de la Cité, was the heart of the first Jewish quarter of Paris as early as the 5th century. Driven out of Paris in 636, the Jews reoccupied this street two centuries later and expanded into the district. It was mainly inhabited by rich Jews.

In the 9th century, they built a synagogue which was located at number 5 of the rue de la Juiverie on the corner with the Rue des Marmousets-Cité. In 1183, Philip Augustus expelled the Jews from the kingdom of France and confiscated their property. The synagogue became the church of the Madeleine-en-la-Cité. In the following century it became a parish. It was closed in 1790, sold in 1793 and demolished during the French Revolution. The part of the Hôtel-Dieu on the rue de Lutèce side is on its site.

A Memorial to the Martyrs of the Deportation was inaugurated in 1962 by General de Gaulle. Former members of the Resistance and deportees wanted to share the memory of the deportation.

Interview of Danielle Malka, National tour guide

Jguideeurope: On your tour guide page, you mention that you especially like to make the stones come alive through the characters. Can you explain this choice?

Danielle Malka: For me, places have a soul, the soul of those who lived there. A guided tour is built around buildings and streets to be discovered in a different way. It’s my role to draw attention to these buildings, these private mansions, to show and tell what you wouldn’t naturally see on your own. To explain an era, a fashion, or why the architect or the owner chose to build the way they did. But just showing stones, as beautiful as they may be, is only interesting if you tell the story of the people who lived there. The visitors see the stone, but they don’t know the history around them. And very often, you have to appeal to the visitors’ imagination to make them feel what was once there. I give keys to identify the era of a building, what makes it special, I rarely talk about it in detail. Take a walk in the Marais. The Pletzel is not really there anymore. I will explain how in the 19th century the Rothschilds founded a school there, how before the war the Rebbe of Loubavitch used to come and teach there. Where the Klapish fish market was, what the open-air market on Rue des Rosiers looked like. Take a walk down the rue Laffitte, the Rothschild mansion is gone. In the days of Grand Baron James and Betty, Balzac, Chopin, Berlioz and others had their napkin rings there. Imagining the dinners, bringing the characters back to life. This is what I enjoy doing and I see that this is also what pleases what the participants of my tours like of my visits. When we talk on the rue de Monceau, how can we not bring back to life those who built their private mansions there? On the Place de l’Opera, how can we not evoke the Pereire brothers who financed so much, and the inauguration, for example, of the Café de la Paix, where Empress Eugenie arrived arm in arm with Emile Pereire. And another hotel round the corner is where Herzl wrote the “State of the Jews”…

What little-known places in this heritage do you like to show?

There are many. When it was possible, I used to start my tour of the Jewish Quarter in front of Notre Dame. Notre-Dame Cathedral is known all over the world. Everyone can recognise its façade. Yet, few people notice the cartoon/sculpture on the Sainte-Anne portal. Who sees the rabbi in talith marrying Anne (mother of Mary) to Joachim, who notices the little schull in the corner with its books and lamp? Joachim wearing the distinctive pointed hat of the Jews in the 12th century so that the illiterate faithful of the time would understand that Jesus’s grandparents were Jewish. Two sculptures of women frame the portals. Who is aware that the one on the right is the synagogue? She is blindfolded by a snake (Viollet le Duc’s idea)… In the Marais, there is also the Hôtel St Aignan, Museum of Jewish Art and History. The building is well known, but who sees the remains of the names of those who had a business there on the columns of the courtyard? The statue of Dreyfus in the courtyard also has a history, and from it one can tell the whole story of the Jews and Zionism in the late 19th and 20th centuries. The Billettes cloister, rue des Archives, also carries the story of a Jew condemned in the 13th century for ritual murder.

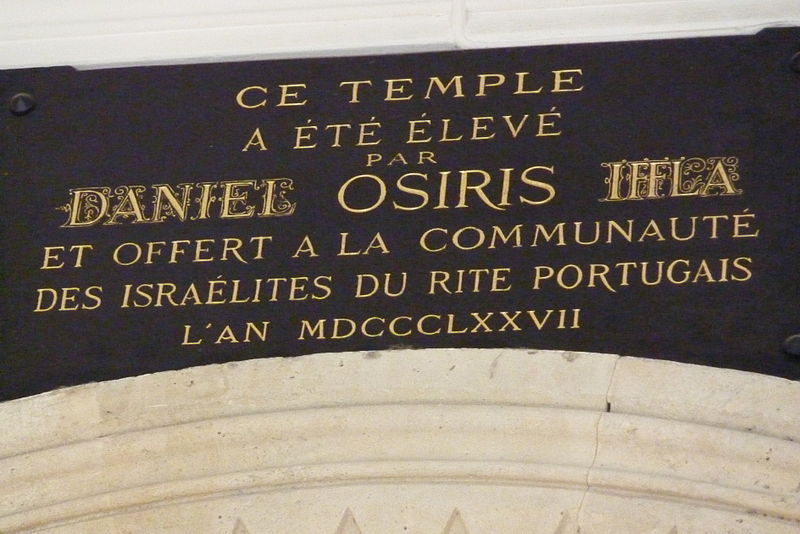

Many non-Jews (and foreign tourists) do not know the Shoah Memorial where I end the tour. The Wall of the Righteous, the Wall of Names. One touches directly on the Shoah, an abstract element of history for many. The dates of birth and deportation of some of the baby brothers and sisters of friends, whose stories I can tell, bring these names engraved on the marble to life. And I also evoke the Jewish Resistance, a discovery for many by taking as an example the story of my parents, Jewish Resistance fighters, which adds a more personal touch. And the role of the Righteous. But in other districts too, we can tell the story of the construction of the two synagogues in the 9th arrondissement. Who knows Daniel Iffla Osiris? Isn’t he a monument too?

On the course of almost all my tours, I find Jewish elements to discover and, to be honest, I take the opportunity to teach. About 70% of the participants in my tours are not Jewish. Sitting in a synagogue in the Pletzl, I explain the main practices of Judaism and it becomes a place for exchange and questions between Jewish and non-Jewish participants. Always in a benevolent way.

Jewish philanthropy is at the heart of my visit to the 9th arrondissement. Making a diversion to the rue Cambon during another visit to the luxury districts of Paris, I stop in front of the hôtel de Castille where Herzl stayed during the Dreyfus Affair. I don’t always go into details, but the elements of understanding are there for those who don’t know.

Can you share a particularly memorable anecdote from a guided tour?

There are many, and I am always moved when, on the occasion of a tour, participants tell me about a part of their family history or discover a part of a story that they have not been told about. Like this meeting once with a lady in her fifties. She knew she was of Jewish origin through her father, but this was not discussed at home and her parents had fallen out with an uncle about whom she knew nothing, not even the reason for the anger. When she arrived at the Shoah Memorial, she was in shock to see her uncle’s name on the Wall of the Deported. She decided to stay at the Memorial and went up to the archives. In the course of her research she discovered that this uncle was still alive. She met him in secret from her family, met her cousins and this allowed the sick uncle to meet with his brother and his family before he died. The cause of the anger? As is often the case, not much. After the war, her parents wanted to forget everything, changed their family name. The uncle remained in his nightmares.