Ukrainian Jewish life has been so diverse in this region, reflecting the many towns and villages and landscapes, but also the many massacres from the beginning of the 20th century to the Shoah. A fortress city like Belgorod, or a place of openness like Odessa, a crossroads of cultures, political movements and night-time festivities, forever inspiring so many artists. These are cities from which emerged personalities who left their mark on Jewish history in very different and complementary ways. From a religious point of view, with Nikolaev, the birthplace of Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson, the ongoing pilgrimages to Uman and Berdichev, a major centre of Hasidism. On the literary front, the inevitable Pereyaslav, where Scholem Aleikhem was born. And of course, the capital, Kiev, with its sublime choral synagogue, the birthplace of Golda Meir. Ukrainian history, culture and worship, or simply at the legendary Savoy hotel in Vinnytsa.

Although Gomel was predominantly Jewish at the turn of the 20th century, very little remains of it today, with a cinema, for example, having replaced a synagogue. The same goes for the Jewish presence in Mogilev, where a synagogue was transformed into a House of Physical Culture. But as you stroll through the region, you’ll have the right to dream of a brighter tomorrow with a visit to Vitebsk, the birthplace of Marc Chagall.

Brest-Litovsk, which had a Jewish majority at the beginning of the 20th century and was best known for the treaty signed there by Trotsky, is one of the most important cities in Belarus. There are also traces, sometimes precarious, of Jewish life in Grodno, known for the great religious activity of Jews and Catholics, the ancient presence of Ruzhany and the Slonim synagogue dating from 1642.

In central Belarus, the main towns linked to Jewish cultural heritage are Bobruzhsk, a typical shtetl, Minsk, where traders worked with neighbouring Russia and Poland, and Mir, which was home to one of the largest yeshivot in the world at the end of the 19th century.

The Jews have a unique and turbulent history on Crete, one of the most important islands in the Mediterranean. Under the Byzantine Empire, Cretan Jews believed the hour of the final redemption had rung: in 430 C.E., a false messiah, the rabbi Moses, promised to lead them all to Jerusalem; they then threw themselves en masse into the raging sea and drowned. Several centuries later, the hand of Venice reached the island, and the Jewish community was forced to live in ghettos. Under Ottoman domination, they were treated more peacefully.

In the mid-nineteenth century, the Greeks themselves protested against grating them a seat in the local chamber of deputies. After a major uprising, punctuated by anti-Semitic incidents, Crete’s autonomy was decreed, a prelude to its reattachment to Greece in 1913. On 6 June 1944, on the very day the Allied army landed in Normandy, 269 Jews from Canea were deported by the Nazis. They all perished at sea in a ship sunk by German planes or, more likely, by an English submarine.

And if the Jews had been of Cretan origin?

Ancient Roman historian Tacitus did not hesitate, in the second century C.E., to voice such a hypothesis. These “Judaei”, he wrote in Book V of the Histories, “might once have been, judging by their name, Idaei”- that is, “neighbors of Mount Ida”, the Cretan mountain towering 8,200 feet above the island.

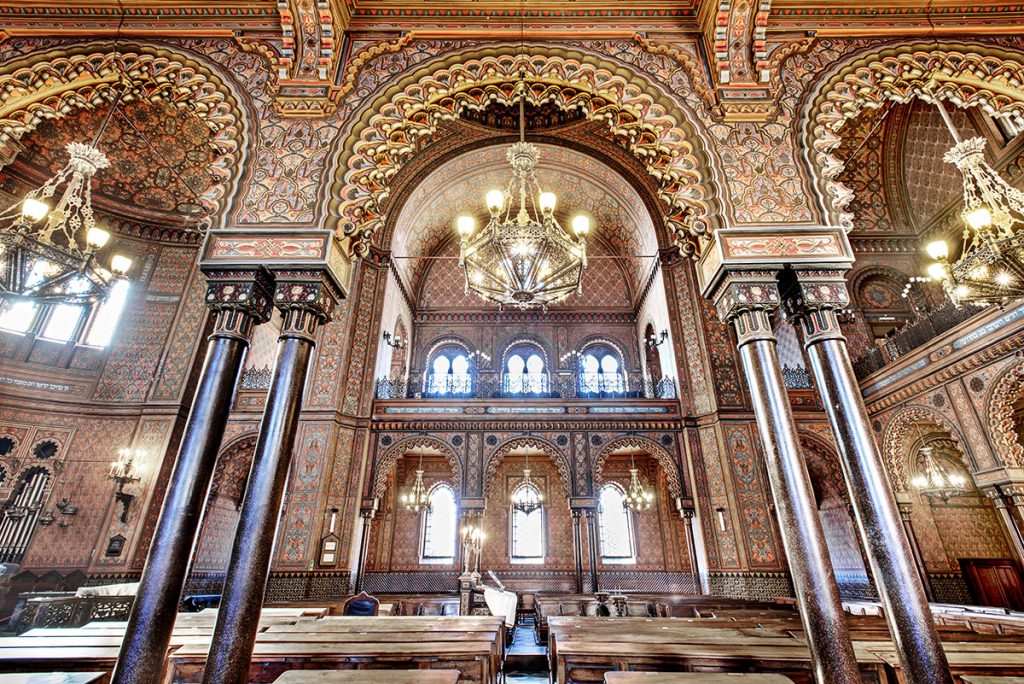

In the Plains region, Jewish life is maintained by the people of Plovdiv, which boasts a beautiful, colourful synagogue for its few hundred worshippers. Efforts are being made to revive synagogues in Ruse, the birthplace of Elias Canetti, and Burgas, which has been transformed into an art gallery. Even more surprisingly, recent archaeological excavations have uncovered a synagogue dating back to the 13th century in Veliko Tarnovo.

Sofia, the Bulgarian capital, is home to a beautiful Sephardic temple, one of the three largest in Europe, as well as a museum dedicated to the rescue of Jews during the war. In a completely different style, you’ll find a listed synagogue in Samokov and a synagogue currently being converted into a cultural centre in Vidin.

The spirit of Austro-Hungarian Cacania still breathes within the medieval cities that lie on the Transylvanian side of the Carpathians, populated until recently by Swabians and Saxons.

Lynxes and bears still haunt the high valleys surrounding Timisoara, the capital of Banat, and the neighboring towns of Sibiu, Sihisoara, Brasov, and Rasnov, characterized by their stocky, Baroque houses of soft lilac, pink, yellow, or pale green colors.

In this region, the majority of Jews spoke German and practiced Reform Judaism, in contrast to Jews to the north. The region stayed Romanian during the Second World War, and the Jewish population, though stripped of their belongings and subject to merciless anti-Semitic legislation, survived before emigrating en masse to Israel and other countries.

So strange a fate for that heterogeneous Jewish community of 400,000 having escaped within Romania’s shrunken borders after the terrible summer of 1940!

How to explain such a large percentage of survivors, perhaps the largest, besides those in Denmark and Bulgaria? Why their mass exodus to Israel and elsewhere, and how was this possible under repressive Communist regimes?

With their customary humor, Romanian Jews admit owing their special situation to a pair of miracle-making rabbis.

The unshakable faith of Alexandre Safran, chief rabbi of Romania from 1939 to 1947, succeeded in thwarting the annihilation of many fellow Jews. He managed to convince the Vatican, ambassadors from neutral countries, and certain members of the political elite (including the queen mother and young King Michael) to beseech dictator Antonescu to postpone indefinitely deportation of “his” Jews.

His Communist-appointed successor, Moses Rosen, a shrewd diplomat with a manipulative mind, opened the doors of Israel to Romania’s Jews. Rosen managed to convince yet another tyrant, Nicolae Ceausescu, to allow Romania’s Jews to emigrate there after years of harassment for being “bourgeois” and dabbling in “cosmopolitanism”. In exchange for considerable financial compensation, many Jews left Romania for Israel in the early 1960s.

North of Wallachia and west of Moldavia, at the center of the Carpathian arc, stretches Transylvania -the land “beyond the mountains”, also called Erdely in Hungarian and Siebenburggen (The Seven Cities) in German.

Dacian warriors resided here until the year 107, when they were subdued by Trajan’s Roman legions, including the Thirteenth Gemina recruited in Judaea. In 217, however, the Roman administration abandoned Dacia after a surge of migrations that culminated with the arrival of the Magyars in the tenth and eleventh centuries.

The twelveth and thirteenth centuries saw an influx of Anglo-Saxon colonists and Swabians from the Holy Roman Empire. They settled at the request of the Hungarian kings to protect against the Turkish and Tatar threat, sheltered by the northern slopes of the Carpathians.

Subject to the Magyar kingdom, then an independent principality, later occupied by the Turks, Transylvania was incorporated into the Austrian Empire in 1691.

Starting in 1867, when the region became Hungarian under the dual Hapsburg monarchy, the largely majority Romanian population living here sought reattachment to Romania; the Treaty of Trianon granted their wish after the First World War.

In 1940, due to pressure by Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy, Bucharest was forced to cede Transylvania’s northwest section to Hungary. The region became Romanian once again at the conclusion of the Second World War.

Although a small number of Jews most certainly appeared with the Roman legions, the first major arrival of those of Sephardic origin took place after the fifteenth century.

They came via trade routes, either from the Danubian principalities or the Ottoman-controlled Balkans. It was not until much later, after annexation by Vienna, that the Ashkenazic immigration from Poland began.

Transylvania’s Jewish population was split between the strictly traditional Yiddish-speaking communities living in the north (between Sighet Marmatiei and Baia Mare, cradle of the often rival Hasidic and Ashkenazic Orthodoxy) and the somewhat Reformist Hungarian and German-speaking ones to the west and south in cities like Oradea and Arad, Timisoara and Cluj, Sibiu and Brasov.

Under the reign of the late Hapsburgs, Transylvanian Jews enjoyed the same rights as the empire’s other citizens, suffering neither discrimination nor marginalization. It was only when the region united with Romania that they had to struggle, with eventual success, for recognition of their civil and minority rights. In the late 1930s, this victory was called into question. From September 1940 to March 1944, the Jews living in northwest Transylvania found themselves under the authority of Hungarian chief of state Horthy, by which they were subjects to anti-Semitic laws as inhumane as those suffered by the Jewish community that remained in General Antonescu’s Romania, whose lives were miraculously spared. In the spring of 1944, practically the entire Jewish population of occupied Transylvania was deported to Auschwitz and gassed. Only a tiny number survived.

Moldavia, with its shtetlach deserted and hundreds of synagogues long closed or destroyed, can be considered a remarkable museum to eastern European Judaism.

First, in Bukovina, several splendid eighteenth and late nineteenth-century synagogues can still be found in towns such as Rădăuți , Vratra Dornei , Câmpulung Moldovenesc , and Botosani .

Further southward in Piatra-Neamt , a rare wooden synagogue dates back to the sixteenth century.

In Bacău, near the synagogue , you can find a small Museum of Jewish History.

The most moving testimony to the Jewish presence in Moldavia undoubtedly remains the sixty-some cemeteries located between the wooded hills of the northwest and the plains in the southwest.

Among them, the cemetery in the town of Siret (formerly a prince’s residence during the nineteenth century, located between the Ukrainian cities of Chernivtsi and Sucavea in Romania) easily rivals the most beautiful ones found in Slovakia, Moravia, Bohemia, and even Prague. And also the cemetery of Radauti , the cemetery of Vatra Dornei , the cemetery of Piatra Neamt and the cemetery of Bacau .

Founded in 1329 by Bodgan I, the principality of Moldavia pitted all those who coveted it against one another -Turks, Austrians, Poles, Cossacks and Russians – for over five centuries.

Deprived of its northern section, Bukovina, annexed by the Hapsburgs in 1775, and Bessarabia, its eastern province later yielded to Russia, Moldavia gained them back when greater Romania was formed after the First World War. At the end of the Second World War, however, it lost them all once more.

Whereas, in Wallachia, the early waves of Jewish immigration were overwhelmingly Sephardic, those that settled in Moldavia were Polish and Ukrainian-born Ashkenazic Jews. Warmly accepted by Prince Stephen the Great in the latter half of the fifteenth century, they were nonetheless segregated from the Christian population. In the seventeenth century, they were massacred by Bohdan Chmielnicki’s Cossacks during their revolts against Polish rule. Over the next two centuries until the time of unification, Jewish community institutions truly began to take root, both in the capital, lasi, as well as the many jewish townships that had multiplied under the Phanariot princes. In 1941, Romania joined the war on Germany’s side, which led to pogroms in lasi and Dorohoi. The Jewish populations of Bessarabia and Bukovina were deported to the other side of the Dniester, where they were victims of hunger, illness, and mass executions perpetrated by the Romanian army.

The art of appeasement

If the Jews of Wallachia were sharp and efficient, the Moldavian Jews liked to weigh their words and take their time before making major decisions. Of a dreamy, ironic temperament, they proved on every occasion their rare spirit of conciliation, as demonstrated by a joke told on the train from Bucharest to lasi, the capital of Romanian Moldavia.

“Once upon a time, in Piatra-Neamt (one of the hubs of Moldavian Judaism), there was a young rabbi who loved to play chess with the owner of a local kosher butcher’s shop. One day, the rabbi disappeared, only to return half a century later. Flabbergasted, his chess partner, now aged and skinny, called out to him:

-But where have you been for all these years, rabbi? Why did you abandon us?

-I was up there, on top of the mountain, said the rabbi smiling.

-And what does a rabbi do over fifty years, all by himself, up there, on top of a mountain? the frustrated butcher grumbled, trying to keep his calm.

-Oh, well, to be exact, way up there on top of the mountain, a rabbi reflects on his life, replied the rabbi.

-And what conclusion did you reach? the butcher exclaimed, now at the point of losing all composure.

Stroking his beard, the rabbi answered:

-My friend, life is like a fountain.

This time, the butcher could not contain himself:

-In the name of …! Fifty years alone on top of the mountain to reflect, only to come up with such a stupid answer? Have you gone mad?

The rabbi stopped stroking his beard, and said in a low voice:

-Fine, if you insist, life isn’t like a fountain!

Although its underground petroleum resources are today largely exhausted, Wallachia remains the country’s economic center.

This region was first dominated by Hungary, but in 1330 it fell under Ottoman influence. A number of Jews expelled from Hungary in the mid-fifteenth century settled on the Wallachian slopes of the Carpathians, and were followed, after 1492, by those expelled from Spain by that country’s Catholic monarchs. Warmly received in regions controlled by the sultan (the Mediterranean shores and the Balkans) and the Wallachian princes, who encouraged trade, Jews in the late fifteenth century nonetheless fell victim to the cruelty of Vlad the Impaler, better known by the name of Dracula.

If their economic importance grew during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the law, which remained medieval, advocated their clear separation from the Christians. While their security was guaranteed under the reign of the Phanariot princes (Christians recruited by the Sultan in Istanbul’s Greek quarter to govern the Danubian countries), already widespread anti-Semitism of Orthodox Christians inspiration led to accusations of ritual murder, abusive tracts, and finally pogroms.

With Moscow’s stranglehold on the Romanian principalities following the 1829 Treaty of Adrianople, the Jews’ legal standing, which mirrored exactly contemporary laws within the czar’s empire, began to deteriorate with the arrival of large numbers of Jewish immigrants in eastern Moldavia, also annexed by Russia. The revolutionary upheaval of 1848, which elsewhere in Europe had called for equal rights for all, failed to live up to its promise. Over the course of the eighteenth century, Wallachia had been acquired by Austria, then passed on to Russia. In 1859, the region was united with Moldavia, forming a new realm that gained independence in 1878.

Despite pressure from French deputy Adolphe Crémieux and other western democracies, and despite Jewish participation in both the war for Romania’s independence and the First World War alongside the Allies (1916-18), civil equality and respect for the minority rights of Jews were not granted until later, by the 1923 constitution. In that era, large Magyar-speaking Jewish populations from Transylvania, German-speaking ones from Bukovina, and Yiddish or Russian-speaking ones from Bessarabia were all united within Greater Romania by the Treaty of Versailles. Fifteen years later, these gains were jeopardized by the anti-Semitic legislation of the Goza-Cuza government. The country’s dismemberment, which began in the summer of 1940, combined with its entrance into war on Hitler’s side against the Soviet Union and then, after defeat, the installation of a hard-line Communist government here ultimately sounded the death knell for Romanian Judaism.

In this region, the town of Wlodawa boasts a particularly interesting Baroque synagogue, built at the end of the 18th century. Nearby is the Sobibor camp, where many victims of the Holocaust were massacred.

The Lublin Plateau bears witness to ancient traces of Jewish life, as evidenced by the presence of 17th-century synagogues in Jozefow, Zamosc and Szczebrzeszyn and an 18th-century one in Kazimierz Dolny. Of course, it is in Lublin that you will find the most places to visit in reference to the region’s Jewish cultural heritage. Its synagogue, its mikveh, its little streets and its long history, notably with the Hebrew printing works of the 16th century.

This vast region includes ancient traces of Jewish life in Lancut, Lesko, Przemysl, Rymanow, Rzeszow and Tarnow, the Ulma family museum in Markowa, major cities such as Krakow, but also the camps of Auschwitz and Birkenau.

You’ll be amazed to discover on our page dedicated to the town of Bialystok the impressive number of synagogues it was home to, even if its name is best known today in popular Jewish culture for the name of the main character in Mel Brooks’ gave it in’ The Producers. The community of Tykocin dates back to the 16th century!

The Lower Vistula region is infamous in Jewish history for the many massacres perpetrated during the Holocaust, particularly in Chelmno. It is in this town that Claude Lanzmann’s film begins.

The region is rich in references to Jewish history, including Gora Kalwaria, long ago dubbed “the new Jerusalem”, the very large pre-war community of Lodz, and the capital Warsaw, where Jewish cultural life flourished until 1942 and even that year, when plays were performed in the spirit of the Resistance in the Warsaw ghetto, where Jews were walled up and starving, before being sent to Treblinka. Warsaw‘s Jewish memory is still alive and well today in a number of places, not least the Polin Museum.

This region of rolling hills punctuated by vineyards merits a two-day visit for memory’s sake. There remains, in fact, little evidence of Jewish life here, as most of it was eradicated by the Shoah.

The several hundred Spanish Jews who arrived on the shores of the Adriatic had a key role for centuries in the development of these coastal principalities, and contributed greatly to their growth and prosperity.

Exploiting their relationships with fellow Jewish settlers in Venice and Constantinople, the Jews of Dalmatia provided an invaluable service to the small cities of the region; pressed up against the mountains, these towns managed to survive thanks only to the delicate interplay between the Ottoman Empire and the City of Doges.

Keeping their own districts but rarely subjects to containment within ghettos, the Jews nevertheless warmly greeted the early effects of the French Revolution, or rather its Napoleonic extension. A decree issued by France’s Marshal Marmont, duke of Raguse (Dubrovnik) on 22 June 1808 guaranteed them the same rights as other citizens.

When Austria took possession of the territories in 1814, it immediately revoked such progressive legislation. Not long afterward, however, Jews won complete emancipation.

The region saw a clear decline over the course of the nineteenth century, due to the enclosed nature of its location and the spiraling breakdown of the neighboring Ottoman Empire. The local Jewish community, already losing its numbers, maintained its meager presence by virtue only of the influx of fellow Jews from Turkish Bosnia, who were escaping an even less enviable economic situation.

During the Second World War, Dalmatia served as a temporary refuge for Jews persecuted elsewhere in Yugoslavia. Mussolini had convinced Hitler to yield him the coast, given that tow of its cities, Rijeka (Fiume) and Zadar, had already been under Italy’s control since the end of the First World War. When the Italian government surrendered in September 1943, the German army rushed to the coast and hunted down all remaining Jews. One segment of the community, however, managed to find shelter in the zones liberated by Yugoslavian partisans. A Jewish battalion even succeeded in forming on the island of Rab, where the Italians had interned some of the community’s members. Generally speaking, the Yugoslavian Jews who were able to escape the Ustashis and the Nazis took an active part in the Resistance, providing Tito’s troops the bulk of their health service.

Reversal of Fortune

Moshe Maralio made the best of his bad luck when the archbishop of Dubrovnik refused him the post of head doctor in the local government. For this Italian Jew, who had emigrated from Barletta in 1494, what mattered was keeping his private practice afloat, for he already enjoyed the respect of both the whole city and beyond: Turkish dignitaries from surrounding Bosnia regularly requested his services. Unfortunately, Maralio fell victim to the rare allegation of having committed a “ritualistic crime”, an accusation sometimes leveled against the Jews of the Dalmatian coast. His trial and that of nine fellow Jews, as pieced together from Duborvnik’s archives, took place 5-11 August 1502. Indicted for having torn out and old woman’s heart, half the defendants were tortured to death and the rest burned alive, despite the seeming lack of proof.

The communities of the southern peninsula were the wealthiest and best integrated in all of Italy during the Middle Ages. This was particularly true of Sicily, where more than 37,000 Jews lived, including a large number in Palermo. This is as many as are living in all of Italy today. The world of the Jews living under the Spanish crown was swept away within a few years after the forced expulsion in 1492.

No trace remains, except perhaps a few place names, like Via Giudecca in the San Pietro quarter of Trapani in Sicily, and a few rare monuments.

The presence of Jews in the Marches dates from as early as the twelfth century. The community developed especially after the expulsion of Jews from Spain, Sicily, and the Kingdom of Naples. There are still remains of Jewish streets and synagogues in a number of small towns in this region bordering the Adriatic coast. This area is off the beaten tourist path and very picturesque.

The Jews were constrained by papal bulls in 1555 and 1569 to live in four cities: Ancona, Urbino, Pesaro, and Senigallia. An intense Jewish life was maintained in these cities until the nineteenth century, and their synagogues are worth visiting.

Until the middle of the nineteenth century and the unification of Italy, very few Jews lived in Lombardy. Today, however, Milan represents the second largest Jewish population in Italy after Rome, with some 9,000 people of some thirty different origins. A large number of these Jews came from Egypt, Lybia, and Iran. It is a dynamic community reflecting the energy of the Lombard capital itself.

Unjustly slighted as a tourist destination, Piedmont is one of the richest regions of Jewish heritage in Italy, with magnificent small Baroque synagogues like those of Carmagnola, Casale Monferrato, Cherasco, Mondovi, and Saluzzo. In 1848, the Piedmontese Jews became the first in Italy to definitively obtain full equality. The main restrictions on their residence or authorized economic activities had been lifted since 1816 in the territories of the Savoy dynasty. The rulers had never dared to fully rescind the rights Napoleon had accorded to the Jews. With the emancipation, the Jews emigrated in greater numbers to large cites, beginning with Turin, and thus abandoned the small cities where the wealthy communities had lived until then. The Jews benefited from a relatively protected situation, and their place in the economic life was already well established.

The ghetto in Turin was not created until 1679, and the ghettos in the other nineteen centers in the Piedmont region, where some 5,000 Jews lived, were not established until the beginning of the eighteenth century. In addition to moneylending and trade in used clothing, the Jews were allowed other economic activities such as goldsmithing, printing, and textiles, especially silk production.

Jews were fairly well represented in elite positions in the administration of the Savoy monarchy, which became the source of the first kings of a unified Italy. Piedmontese Jews also played a significant part in the economy and cultural life of the region. Large synagogues were built in the region toward the end of the nineteenth century: a neo-Byzantine synagogue in Vercelli, a neo-Gothic synagogue in Alessandria, and a large neo-Moorish structure in Turin. The local community in Turin had at first commissioned architect Alessandro Antonelli, who emulated the transalpine style of Gustave Eiffel in creating a “tower synagogue” in steel rising to a height of over 500 feet, whose purpose was to celebrate not only the Jewish community’s newfound power but also its modernity. Lack of funds, however, forced the Jewish community to forfeit the half-finished work. The municipality revived the project and completed the Mole Antonelliana, which became the National Independence Museum.

Jews from Piedmont payed a high price during the Second World War -there were 4,000 Jews in the region in 1939 and fewer than 2,000 in 1945. Despite this tragedy, the community remained active after the war and included such prominent members as the businessman Adriano Olivetti and the intellectuals and writers Primo Levi, Carlo Levi, and Natalia Ginzburg.

My ancestors

“Rejected or given less than warm welcome in Turin, they settled in various agricultural localities in southern Piedmont, introducing there the technology of making silk, though without ever getting beyond, even in their most flourishing periods, the status of an extremely tiny minority. They were never much loved or much hated; stories of unusual persecutions have not been handed down. Nevertheless, a wall of suspicion, of undefined hostility and mockery, must have kept them substantially separated from the rest of the population, even several decades after the emancipation of 1848…”

Primo Levi, The Periodic Table, Trans. Raymond Rosenthal (New York: Schocken Books, 1984).

The rich region of Emilia-Romagna is definitely worth a week visit. Located on the south of the floodplain of the Po River, it includes cities like Bologna, home to a museum that is a model of modern installation techniques and location of the ruins of an ancient ghetto in the heart of the city, and above all, Ferrara, once a very important center of Italian Judaism.

A leisurely tour of the region will allow for a visit to its many monuments and evidence of a Jewish past that dates back to the Middle Ages. The history of the numerous small communities in the region varies considerably according to their location. In the Papal States, which includes Bologna and Ravenna, severe persecutions began as early as the fourteenth century.

The forced ghettoisation of the Jews in the small towns of Romagna (Rimini, Forlì) erased the active communities of those towns. In Modena or Ferrera, possessions of the dukes of the d’Este family until 1598, the Jews fared much better, as the rich heritage they left behind attests today.

With cities like Livorno and Florence, Tuscany represents an important part of the history of Jewish life in Italy, although evidence of the longstanding Jewish presence here is less abundant than in Venice and Piedmont. The large free port city of Livorno was the largest Jewish city of Italy between the seventeenth and nineteenth centuries.

The powerful Spanish-Portuguese community had what was considered to be one of the most sumptuous synagogues in Europe along with that of Amsterdam. Florence’s richly decorated Grand Temple, completed in 1882, stands as one of the most luxurious of those erected after the Jews’ emancipation.

Small Jewish communities have lived in the region since the Middle Ages. Early records demonstrate a stable presence -thanks to the Medicis- of Jewish moneylenders in Florence from the beginning of the fifteenth century. The Medicis remained well disposed toward Judaism for almost a century. Cosimo I readily welcomed the Jews fleeing the Papal States in 1555. Several years later, however, Cosimo I buckled to papal pressure and forced the Jews of the Grand Duchy to live in two ghettos, one in Florence and the other in Siena.

In 1593, Cosimo’s successor Ferdinand I took a more pragmatic and tolerant political stance and encouraged the Jews, especially those who had fled the Iberian Peninsula a century earlier, to settle in Livorno in order to develop the Grand Duchy’s commerce with the Levant. The small city of Pitigliano, near the former border with the Papal States, was another center of Judaism. Refugee Jews awaiting better times in Rome settled here in the sixteenth century. Their descendants stayed in Pitigliano until the emancipation of the Jews in the middle of the nineteenth century.

It is likely the history of Spain’s Jews began in Estremadura. Vestiges from the third century bear witness to them, and, according to the twelfth-century chronicler Abraham ibn Daud, the Jews that Titus deported from Jerusalem settled in this old Roman province. However, as elsewhere, there are few traces left to indicate this long presence.

It is possible to date the presence of Jews in Andalusia to the Council of Elvira (303-09), when references were made to the need to separate Jews and Christians.

There have been Jews in the Balearic Islands since the Roman occupation. After Jaume I won the islands from the Arabs, many Jews arrived from Catalonia but also the south of France and North Africa to settle the new land. After 1343, when Pedro IV of Aragón seized the islands, the Balearic Jews began to enjoy a real golden age. The leading families traded throughout the Mediterranean and with North Africa, where they set up a highly efficient network of commercial agents. They also specialized in silver and gold and jewelry, as well as moneylending. They owned fine houses in the call at Palma de Mallorca and kept slaves. The community had its own laws and was directed by six secretaries and a council of thirty notables. Among its best-known men of learning were the rabbi Simon ben Zemah Duran, a great Talmudist who went into exile in Algiers, and the cartographers Abraham Cresques and his son Jafuda Cresques.

In 1391 the call was besieged. Many died, and forced conversions followed. Some chose exile and left for Algiers. In 1435, after an accusation of ritual crime, the shrunken remainder of the community underwent forced conversion almost to a person. From this date onward, there were officially no more Jews. Jewish life continued only in a very diffuse form, among the chuetas, or crypto-Jews. They formed an extremely closed society of silver – and goldsmiths and jewellers whose integration into Majorcan society has remained problematic even in recent times.

In the Middle Ages, the powerful kingdom of Aragón comprised not only of Aragón itself but Catalonia, Valencia, and the Balearic Islands. It was home to numerous Jewish communities, especially after the union with Catalonia in 1150. They had links with the Muslims, who lived here around 1500.