A small region in terms of size, it has a large population, thanks in particular to the cities of Bilbao, San Sebastian and Vitoria. Between its very different landscapes, combining sea and mountains, there are numerous dolmens and menhirs. The most surprising Jewish presence in this region is linked to the very special history of the Jewish cemetery in Vitoria, which you can discover on our page dedicated to the city.

The Murcia region has been inhabited since prehistoric times, as archaeological excavations have shown. Often conquered by different peoples, it became famous for its agricultural development thanks to an efficient and ancient irrigation system.

Few traces of Jewish life remain in this region, but one of the country’s most astonishing is to be found in Lorca, where recent archaeological excavations have uncovered one of the oldest and only pre-Inquisition synagogues to have been preserved in its original state. You’ll also be amazed to read on our page dedicated to the city where it was located…

Small in size, La Rioja is big on wine. It is also famous for its monasteries and the Pilgrim’s Way to Santiago de Compostela. Although the Jewish presence in this region goes back a long way, it is mainly in Calahorra that you will be able to appreciate it. Take a stroll through the old Jewish quarter, or discover the vestiges preserved in its museums.

A very ancient region, Galicia has been marked by the Roman conquest, particularly in terms of architecture, such as the Tower of Hercules, the last active Roman lighthouse. But also by the Galician language which results from it. Galicia is a region with many traces of the ancient juderias. Will you fall under the medieval spell of Monforte de Lemos? Will you be dazzled by the buildings in the Jewish quarter of Ribadavia? Surprised by a menorah carved into a cathedral in Tui?

The region of Castilla-La Mancha is the heir to the region of New Castilla, from which the province of Madrid was extracted. While nearby Madrid has been Spain’s capital for centuries, Toledo is undeniably perceived as the “Jerusalem of the Sephardic Jews”. With its many sumptuous, ancient synagogues, two of which still stand today. Find out more about the history of the city on our link, as well as an interview with the director of Toledo’s Jewish Museum.

Thanks to its geographical position and long coastline, this region has been the scene of numerous encounters and conquests. The Valencian Country was formed following the conquests of James I of Aragon in the 13th century. Less well known than Cordoba and Toledo, the town of Sagunto nevertheless bears witness to one of the oldest traces of Jewish presence, dating back to the 2nd century. Find out more about its history and places to visit.

The Jewish presence in Sicily seems to date back at least two thousand years. Some archaeological traces and the lives of personalities of the time, such as the historian Caecilius of Calacte, attest to this. The various conquests of the island, particularly by the Arabs and the Normans over the centuries, also evoke their presence. The cities of Palermo, Syracuse, Naso, Messina and Catania are all examples.

In 1171, Benjamin of Tudela mentions in his famous travel diary the existence of Jewish communities in the cities of Palermo and Messina.

In the 14th century, Frederick II (1296-1337) protected the Jews from the persecutions of the Crusades and religious threats, also allowing them to practice different trades, especially in silk processing. However, they were not allowed to practice medicine or governance. Frederick III gave similar protection to Jews from religious threats.

From the end of the 14th century to 1474 the situation of the Jews improved, especially with the lifting of occupational and urban restrictions.

Nevertheless, in that year 360 Jews were massacred in the town of Modica. And probably about 500 in Noto. The chain of violence continued, despite the occasional attempt by leaders to protect them.

Following the measures taken by the Inquisition in Spain, the 30–40,000 Jews of Sicily were forced to leave the island when a decree was issued in 1493.

Most left, some converted, and others lived as Marranos. There were then about fifty communities, the largest of which was Palermo with 5,000 Jews.

Few Jews returned since, despite some attempts in the 18th century mainly. It is estimated that in 1965 only about 50 Jews lived there. Nevertheless, contemporary research shows that there are many Sicilians who probably have Jewish origins.

Renewed interest in the island’s Jewish cultural heritage was sparked by the discovery of a mikveh in 1987 in the city of Syracuse. Especially since the mikveh was very well preserved over time. Rabbi Di Mauro, who was born in Sicily before emigrating to the United States, returned to the island in 2007 and re-established Jewish life.

In the 2000s, associations began to organise festivities, research, and conferences in Palermo, notably by the Italian Institute of Jewish Studies, in order to highlight the Jewish history of Sicily. This was done in connection with the Jewish community of Naples, the main one in southern Italy.

Competing with Corsica for the most beautiful beaches in Europe, Sardinia is obviously a very popular destination in summer. And for its nature parks, with their rare species of animals and plants.

Craftsmen, merchants, intellectuals, rabbis, winegrowers… many professions bear witness to the diversity of European Jewish life in the Middle Ages. But they were also soldiers, taking part in the conquest of Sardinia by Peter IV of Aragon in the 14th century. Following this conquest, some of them settled in Alghero and opened a synagogue. However, Sant’Antioco has even older traces of Jewish life, dating back to Roman times!

Umbria is a region in central Italy known for its charming little villages and medieval buildings, such as Orvieto Cathedral and Carbonana Castle.

Although Jewish life in Perugia goes back a long way, as evidenced by a 1279 law ordering their expulsion and, above all, a manuscript from 1414, short films from the 1920s showing religious events have been shown to the public. Admittedly, these works are less famous in the region than Al Pacino’s filmography, but he made his debut on foreign stages in Spoleto, starring alongside John Cazale in a play by Israel Horovitz.

The Friuli-Venezia Giulia region is well known for its art villages, some of which have been listed as World Heritage Sites, as well as for its gastronomic tourism, with a wide range of local specialities, and winter and summer sports.

Archaeological digs in the region have traced the Jewish presence back more than two millennia, as witnessed by the epitaph written for one of the Jewish inhabitants of Aquileia. Museums in some of the towns in the region preserve this ancient presence, such as the archaeological museum in Cividale. Parts of buildings such as an old synagogue have been found in Cormons. The link between the Jews and the region is not just architectural and cultural.

Great families such as the Morpurgos achieved great success in the manufacture of silk and wax in Gorizia. They also made their mark in other commercial fields in Gradisca d’Isonzo. The Luzzattos of San Daniele del Friuli were also prominent in the cultural sphere. Intellectual activity was also encouraged by the richness of the region in this area, which didn’t wait theRenaissance, as did also the University of Udine.

More recently, Jewish life in Trieste remains the most important in the region, with its 20th-century landmarks: the synagogue, the Café San Marco, the Umberto Saba bookshop and the very important Carlo and Vera Wagner Museum.

The small Mediterranean region of Liguria is famous for its long beaches and nature parks. But also for the important place in maritime history of its main city, Genoa.

Although Liguria is not the region best known for its Jewish life, it is worth noting that it was in Genoa that the first Bible in several languages was published in 1516. The text even contains footnotes about Christopher Columbus!

The Campania region is renowned for its long and rich history, both ancient and contemporary. From the ancient monuments of Pompeii and Herculaneum to more recent ones such as the Vanvitelli Aqueduct and the Palazzo di Caserta, and of course the bustling city of Naples, which has featured in films from the post-war period to Paolo Sorrentino’s, not forgetting its mythical stadium.

The Jewish presence in the Campania region goes back a very long way, and the sources found to attest to it are sometimes remote. One example is a 10th century letter found in a genizah in Cairo, referring to the Jewish inhabitants of Amalfi. At that time, the town of Benveneto had its own yeshiva and Naples its own synagogue. Benjamin of Tudela met almost 500 Neapolitan Jews in the latter synagogue in 1159.

As for Pompeii, famous for its volcano and historic eruptions, it was home to Jews as long as two millennia ago, as you can see from the traces found in its ruins. But that doesn’t mean you can’t be moved by more recent cultural heritage too, such as a Passover Haggadah from Capua used by Israeli soldiers in the British forces during the Second World War.

The South is very different from the rest of the Italian peninsula because of the Jewish presence that was brutally interrupted by the expulsion of 1510, as this is reflected in the rather small archaeological heritage.

In Calabria, Jews did not live in the isolation of ghettos, but in their own neighborhoods, the “Giudecche”. Near Vibo Valentia (formerly Monteleone), on the splendid Tyrrhenian coast, you’ll find the Jewish quarter of Nicotera, one of the largest in Calabria, founded by Emperor Frederick II in 1211, which is well worth a visit. A little further on, on the hills, you can marvel at the “Giudecca” of the charming village called Arena, and not far away the “Giudecca” of Soriano Calabro, where craftsmen and especially Jewish dyers thrived and where you can find the traditional cakes with ancient Hebraic recipes, the “mostaccioli”, made from flour, honey and almonds.

The Orthodox Jewish community today does not exist as such in Calabria, as there are few practising Jews and a few dozen are on their way back or converting to Judaism. For this reason, Calabria depends on the community of Naples, but it is rich in Jewish history. However, a new breath of fresh air has come from the United States thanks to a progressive Jewish woman, Rabbi Barbara Aiello, an American-Calabrian, who is determined to contribute to the resurgence of the anusim, the descendants of the Jews of the south who were forced to convert at the beginning of the 16th century. In 2007 she created the Ner Tamid (Eternal Light) synagogue in Serrastretta (province of Catanzaro), with the aim of reviving this Calabrian Judaism that has existed for centuries in a latent state and that was just asking for it under the southern Italian sun.

Of all this Calabrian history, we recall that Shabbetay Donnolo, a famous physician and philosopher, operated in Rossano around the year 1000; that in Reggio Calabria, on 5 February 1475, Rashi’s commentary on the Pentateuch was printed, the first work in Hebrew with the date indicated. Moreover, the parents of the great Kabbalist Hayim Vital, known as “il Calabrese”, came from the region.

It is worth noting that the 4th century synagogue of Bova Marina, rich in mosaics, the oldest in the West after that of Ostia Antica, bears witness to a flourishing community. Archaeological evidence of the Jewish diaspora can also be seen at the National Archaeological Museum of Reggio Calabria, at the Antiquarium Leucopetra di Lazzaro, a hamlet in Motta San Giovanni, in Vibo Valentia, and at the National Archaeological Museum of Scolacium in Roccelletta di Borgia.

On the Ionian coast, in Monasterace marina, near Riace marina, where the two bronze giants were found, you can visit the Library of the Agafray Cultural Association, which was opened by the sister of Agazio Fraietta, an enthusiast of Jewish culture who has passed away, to raise awareness among Calabrians of their cultural heritage, particularly Hebraic. It features a library with a wealth of documents on the region’s past, as well as recreational activities relating to the region’s artistic activities.

Nowadays, in the province of Cosenza, there is Ferramonti, the remains of the concentration camp for foreign Jews, built during the last world war. On the Cedar Coast (between Tortora and Cetraro, concentrated around Santa Maria del Cedro), every year in August, rabbis from all over the world come to harvest the excellent Calabrian citrus fruits that are an integral part of the Sukkot celebrations.

In Cosenza, for the recurrence of the Jewish Festival of Lights, a majestic candelabra is publicly lit in Largo Antoniozzi, in the historic centre, near the old Jewish quarter. In addition, the Calabria Kosher Food Festival was inaugurated in 2019.

A curiosity: in Reggio Calabria, the tourist can walk along a beautiful street dedicated to Aschenez (great-grandson of Noah) who, according to a legend, founded this beautiful city that looks out over the Mediterranean.

Text written by Riccardo Guerrieri

Our interview with Lina Fraietta, about a wonderful project created in the town of Monasterace, a library enabling researchers and visitors to find out more about Calabria’s Jewish cultural heritage.

Jguideeurope: How did the library project come about?

Lina Fraietta: The Agafray Library is managed by the Agafray Cultural Association. The Association was born in memory of my brother, Agazio Flaviano Fraietta. Agazio, although he had no academic degrees, was a passionate scholar and researcher of Calabrian culture and the history of Jews in Calabria.

Over the past few years he had collected more than 2,500 books and objects both Calabrian and Jewish, which now constitute the library holdings of the Biblioteca Agafray, based in Monasterace, where Agazio was born.

A department dedicated to children and young people has been added, on my initiative, with books and the initiation of several creative workshops for children.

Since one of the objectives of the Library is to make the territory known, connected with the Library is a vacation house “Agafray house” in a nearby town: Sant’Andrea Apostolo dello Ionio. The house favors stays for members of the Association and for those who want to get to know Calabria.

Is it involved in any cultural or educational projects in the region?

The Library and Association place themselves at the service of citizens; several events have since been proposed and organized under the patronage of local institutions, especially the Municipality of Monasterace where the Library is located. It is currently not involved in specific school or regional projects.

What book on Calabrian Jewish heritage has particularly impressed you?

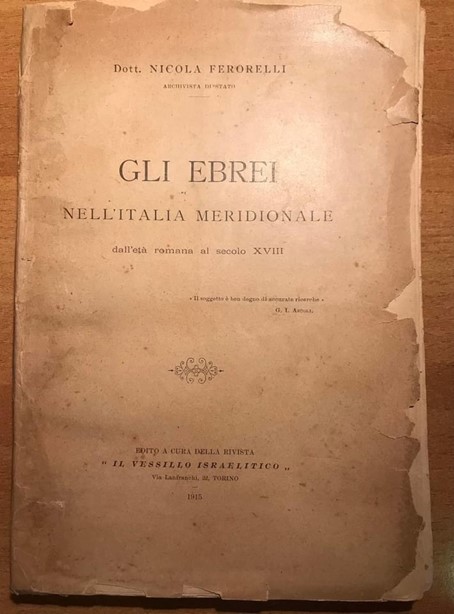

There are several books on Jewish heritage and in the possession of the Library that have impressed me, although few authors and researchers have dedicated themselves to this topic; I will mention one out of all: “Gli Ebrei nell’Italia Meridionale”, by Nicola Ferorelli, whose photo is reproduced here.

The Basilicata region is famous for its ancient buildings, in particular the prehistoric settlements at Matera, which have been declared a World Heritage Site.

Some of our pages mention the Jewish presence since Roman times, in various countries conquered by Rome 2,000 years ago, including France and Spain. In the Italian region of Basilicata, the Jewish presence also dates back to this period, as attested by Hebrew inscriptions and a menorah carved in the catacombs of Venosa.

The Abruzzo region has historical traces dating back to the Neolithic period. Today, the region is best known for its national parks, medieval castles and long stretches of beach.

The Jewish presence in this Italian region dates back to the 13th century, thanks to the decision of the King of Naples, Ladislaus, particularly in Aquila.

This region of Ukraine bears witness to the desire to share the Jewish culture of yesteryear. The building that once housed the Berehove synagogue is now covered in a reproduction of its façade. But also the rebirth of Jewish life in Uzhhorod after the Shoah, as evidenced by its sublime renovated neo-Byzantine synagogue. And let’s not forget Mukachevo and its progressive Jewish school from the 1920s, a place of cultural ferment where the great contemporary painter Samuel Ackerman was born.

The Centre-Val de Loire region is of course famous for its châteaux on the banks of the Loire, but also for its cathedrals, particularly those at Chartres, Orléans, Tours and Bourges.

The Jewish presence in the region is very old. It appears to date back to the 6th century in Bourges and Tours, and the 12th century in Chinon. Recent archaeological digs in Châteauroux also attest to this, as does the intellectual activity of the Tossafists in Dreux.

Later in history, this cultural heritage – the Rue aux Juifs in Chartres – inspired a novel by Zola. The region is also marked by the Second World War, with homage paid to the Righteous, such as a nurse in Tours, but also to deputy and minister Jean Zay in Orléans, as well as the creation of a Resistance, Deportation and Remembrance Centre in Blois.

The presence of Jews in Lorraine dates at least from the Carolingian period. In the Middle Ages, the main administrative documents found relating this presence were mainly linked to expulsions. In the cities of Metz, Verdun, Toul, Nancy, Lunéville, Sarreguemines…

The first great Jewish figure being Gershom Ben Yehouda, who was born in Metz in 960.

In the centuries that followed before the French Revolution, there were back and forth trips depending on authorizations to settle and charges of all kinds and expulsions. Thus, the city of Boulay had a synagogue in the 17th century.

In 1733 there were 180 Jewish families in the region. A rabbi was officially appointed three years later. In the 1780s, synagogues were built in Lunéville and Nancy. Among the important players in the emancipation of the region’s Jews during the era, Isaac Behr and of course Abbot Grégoire.

During the French Revolution, 500 Jewish families were counted in Lorraine, 90 of which were in Nancy. Two central consistories were created in Metz and Nancy.

These two towns, with 6,500 and 4,200 Jews respectively, received the vast majority of the region. Synagogues were then built in Epinal, Phalsbourg, Sarreguemines, Toul and Verdun.

Following the conflict of 1870, many Jewish refugees from Alsace and Moselle moved to Lorraine. The Jewish population gradually increased until World War II. The leaks and the large number of deaths in the region during the Holocaust drastically reduced this number.

The arrival of a few hundred Jewish families from North Africa in the 1960s helped rebuild Jewish life in the region after the war. The Jews of Lorraine now live mainly in the cities of Metz, Nancy, Sarreguemines, Thionville, Lunéville, Forbach, Epinal, Sarrebourg and Saint-Avold.

Little is known about the history of the Jews in Gallo-Roman Armorica before the Council of Vannes which, around 465, legislated on their relations with clerics.

Their ancient and lasting establishment in Brittany is however attested in the 13th century, in Rennes, Fougères and, above all, in Nantes. The anti-Judaism which marks the crusades ends after a period of looting and murder, in their expulsion from the Duchy (ordinance of Ploërmel, April 10, 1240).

It was not until the 17th century and especially the 18th century to find traces of their presence in Nantes, but also in Saint-Malo and Rennes, frequenting the great fairs of Brittany.

Having become French citizens, the Jews experienced a long period of peaceful life in the 19th century. Very few in number; they are hardly more than two hundred throughout Brittany, but nevertheless form dynamic communities in Brest and Nantes, where in 1871, the first synagogue in Brittany was inaugurated.

The anti-Semitic violence of 1898 and 1899, (year of the second Dreyfus trial in Rennes) did not spare the region. Leading academics were teaching in Rennes at the time: Henri Sée, Victor Basch, the latter was founder (on January 22, 1899) of the Rennes section of the Human Rights League which, in ten years, grew from 21 members to more than 600.

The presence of Jews at the time of the Second World War is authenticated by the commemorative plaques installed in the community center, recalling the names of the 70 families deported from Ille et Vilaine: 131 (250 disappeared for the whole of Brittany).

It was in the early 1960s that the Jewish community of Rennes was formed in an organized form with mainly Jewish families from North Africa joined by a few Ashkenazi families, including survivors of the extermination camps.

In 1963, a first association was born, chaired by Mr. Rozenfeld who organized meetings at his home and who organized the first office of Yom Kippur. Subsequently, on each Yom Kippur, the Hall of Fine Arts was rented to accommodate the offices led by an officiant who came from Paris with a Séfer.

At the end of 1969, the relentless activity of a group of friends gathered around Mr. Henri Ohana led to the inauguration of the first premises allocated by the municipality to our community now under the presidency of Mr. Jacques Habib. We obtained from the mayor Mr. Henri Fréville a very small room then a second less cramped room still in the district of Maurepas.

Later, the municipality granted an apartment in the Maurepas neighborhood house where it was possible to build the first synagogue worthy of the name and which dominated the community for twenty years.

In the twenty-first century, the combined efforts of the Mayor, Mr. Edmond Hervé, the Safra Foundation, the Jewish community and its president, Mr. Bernard Lobel, led to the construction of a real cultural and religious center, the Edmond Center. J. Safra, which was inaugurated on January 20, 2002.

(Source: Israelite Cultural & Religious Association of Rennes)

The Burgundy-Franche Comté region is home to a number of World Heritage monuments, including the basilica at Vézelay and the citadel at Besançon. The region also boasts vast natural areas, with forests, mountains and lakes.

If, following Jacques Brel’s advice, you visit Vesoul, you’ll find a synagogue dating from 1875. This was a period when Jewish life in the region was marked by the construction of other synagogues. These included the Moorish-style synagogue in Besançon and the neo-Byzantine synagogue in Dijon. Jews from Alsace also settled here after the 1870 war, expanding the communities, including those in Belfort and Montbéliard. Nevertheless, the Jewish presence in the region is much older, as evidenced by the Hebrew inscription on the clock tower in Auxerre and the name of the town of Baigneux-les-Juifs. Not to mention the intellectual activity of the Tossafists of Joigny and Sens and the birth of regional Jewish winegrowing vocations in Mâcon, Chalon-sur-Saône and Chablis.

Jewish life in the suburbs of Paris is as diverse as the suburbs of the capital and the towns and cities of the region. It is diverse in terms of its historical origins, its economic situation, its cultural development and its religious life. There have also been contemporary upheavals with migration following the resurgence of anti-Semitism since the turn of the 21st century.

For example, the large Jewish presence in the working-class districts of the north of Paris, such as Aubervilliers, Bobigny and Sarcelles, only lasted half a century. From the early 1960s, following the arrival of large numbers of Jews from North Africa, until the first decade of this century. The Drancy camp, where tens of thousands of Jews passed through on their way to the extermination camps, is a place steeped in memory in this département.

Most of the Jewish communities in the region named Ile-de-France developed in the second half of the 19th century, although their presence goes back much further. The synagogues built during this period in Fontainebleau, Neuilly-sur-Seine and Versailles bear witness to this. Those in Vincennes-Saint Mandé, La Varenne Saint-Hilaire and Boulogne were built in the 20th century, the latter close to the sumptuous Albert Kahn gardens. As a symbol of this long shared history and the republican battles fought together under the French flag, a Dreyfus museum opened in Médan in 2021 next to the museum of the House of Emile Zola, who published his famous “J’accuse” in defence of the famous captain.

The Medieval Route of Rashi in Champagne, new route of the Council of Europe Jewish Heritage Route

By Delphine Yagüe – CulturistiQ Cultural laboratory – RMRC project manager

In the heart of the Aube, the former county of Champagne, rich and powerful, had prestigious prosperous medieval Jewish communities from the 11th to the 13th centuries: Troyes, Ramerupt, Dampierre, Villenauxe, Lhuître, Ervy-le-Châtel, Chappes, St-Mards-en-Othe, Bar-sur-Aube, Mussy-sur-Seine, Brienne, Plancy, Trannes … Apart from the current Department of Aube, it also included other Jewish communities in Vitry, Provins, Joinville, Sens or Château-Thierry… After Rashi, born in Troyes in 1040, many scholars originally installed in the villages of Champagne, claim to be from his École champenoise and influence other Jewish communities in the interpretation of the Bible and the Talmud.

The name of the prestigious county of Champagne then spread through all the Western Jewish communities through them. Their comments and legal decisions are the only testimonies of that time, attesting to intense intellectual activity and a flourishing local Jewish life. The native language of the Jews of Champagne is Champagne, dialect of the language of Oïl. They speak and know Hebrew poorly. Also, in their comments, the Sages of the Jewish communities often translate Hebrew words into Champagne and describe situations of daily life there. A method that facilitates access to reading and studying sacred texts. They thus transmit to us the words of a forgotten living language and very many testimonies on the local life of the time: trades, clothing, fauna, flora, relations between Jews and Christians, organization of the county…

Rashi’s sons-in-law and grandsons founded the Tossafist school. It first radiated from the village of Ramerupt until 1146. Dampierre then Sens – then located in the county of Champagne -, then took up the torch. When the county entered the kingdom of France between 1285 and 1305, Paris became the epicenter. Great educators, Rashi and the Tossafists sometimes use drawings and describe their daily lives in their comments, in order to better explain the laws and concepts of sacred texts. Thus they give a lot of information on the tools and techniques allowing to work the vine and to produce wine, but also to make bread, to work the glass or to build houses or wells. They are true passers of history and unknowingly leave us with the fundamental elements which today make up the exceptional heritage of the Aube and in particular the cultivation of the vine, the production of wine (from Champagne) and the art of stained glass!

It is the story of this strong Jewish presence and of the fruitful and original daily, intellectual and economic interactions and relationships between Jews and Christians that the Medieval Route of Rachi in Champagne has sought to promote since 2019. This Route, a new European Cultural Route integrating the Council of Europe’s Jewish Heritage Route, aims to promote the Jewish memory of the Department of Dawn, an invaluable cultural heritage shared by Jews around the world and the historic heritage of a territory of very first plan – the former county of Champagne – with national and international influence.

To energize the territory, it is currently implementing numerous projects to create a global cultural and tourist offer around the history of the former Jewish communities of Champagne in Troyes, in the villages of Aube and beyond. A difficult challenge in the context of the promotion of an intangible cultural heritage, but fascinating and unifying around many local, national and international actors among communities, associations and scientists. On the program to come very quickly: tourist activities in the territory, program of exhibitions, signage, creation of new visiting devices … To discover step by step, on the page of the Departmental Committee of Aube carrying the project.

The Hauts-de-France region is particularly well known for its castles (Chantilly, Pierrefonds and Compiègne), numerous medieval fortifications and cathedrals, especially those of Amiens, Beauvais, Laon and Soissons.

Although the return of Jews to the northern region was encouraged by the emancipation granted in the wake of the French Revolution, their presence goes back a very long way. In Lille, for example, which boasts a beautiful synagogue inaugurated in 1891, their presence dates back at least to the 11th century. It was probably a century later in Soissons, where many Righteous Among the Nations were recognised. Another place steeped in history linked to the Shoah is the Internment and Deportation Memorial at the former Royallieu camp in Compiègne.

As you can discover on the page devoted to the Georgian capital, Tbilisi is home to a number of sites linked to Jewish cultural heritage in the old town. One of these is the astonishing synagogue built of red bricks. Less expected in the region is a small synagogue in Gori, the birthplace of Stalin!

On this road you’ll find the town of Akhaltsikhe, with its ancient Rabati quarter housing the country’s oldest synagogue, as well as another built in the 20th century. Once you’ve crossed the road and set down your bags in Batumi, you’ll be dazzled by the synagogue built between 1900 and 1904 on the Tsar’s authorisation!

Surprising discoveries await you in northern Georgia. From Kutaisi, with its great synagogue dating from the late 19th century and its famous translator Boris Gaponov, to Oni, with its sublime synagogue dating from the same period and recently restored.

In 1815, North African Jews whose ancestors had been expelled from Spain came to the Azores. The island was duty-free and allowed them to import and resell to local businesses. In 1820, the Portuguese liberal revolution led to religious diversity.

In 2004, a genetic study concluded that 13.4% of the Y chromosome of Azoreans is of Jewish origins, a fact that suggests the importance of the Jewish presence in the Azores over many centuries. There are 3 major instances of the Jewish presence in the Azores. The first dates back to the original settlement of the Azores in the 15th century; the second takes place in the first quarter of the 19th century; and the third coincides with the Nazi period. During the Second World War, the Azores became a haven for German and Polish Jews who managed to flee Europe. Commerce was the main economic activity of the Azorean Jewish community.

The first documented Jewish settlement began in 1818; by 1848 the number rose to 250. Most of the community lived in Ponta Delgada. There’s also a Jewish cemetery in Santa Clara.

In an abandoned synagogue in the Azores, far from the historical centers of Jewish life, the Azorean Heritage Foundation, whose mission is to bring to light the history of the now extinct community of Sha’ar HaShamaim (Gate to Heaven) that was established in the town of Ponta Delgada in 1821 by a group of Moroccan Jews. The community’s small synagogue, which had been for years in disrepair, has been restored. The geniza materials -filling about 50 large boxes- have been recovered and deposited in the Municipal Archives of Ponta Delgada.

The contours of the community have begun to emerge thanks to the documents found in the geniza. Communal documentation and commercial letters confirm that this was a mercantile community dominated by a few wealthy families. It was a distinctly North African community, but strongly oriented toward Europe. A commercial letter discussing trades in textiles mentions Liverpool, Lisbon, and Hamburg as cities that were part of the trade network.

The community thrived for generations, but in the 1940s, its number had so dwindled, through emigration and conversion, that the synagogue did not have a minyan.

In February 2014, on the island of San Miguel, the restoration of the synagogue began. It was built around 1820, and consecrated in 1836. It is Portugal’s oldest synagogue, built after the Inquisition.

The synagogue, which had held services in the 1950s, is located on the upper floor of a building that also included the rabbi’s house. The narrow building has plain walls, arched windows, an ornate chandelier, and wooden fixtures, including the Ark, benches, a bimah, and wall panelling. The restored synagogue includes a museum and library in the building’s complex. In 2009, the Lisbon Jewish community donated the synagogue to the Ponta Delgada city hall, on a 99-year concession in exchange for guarantees that it would be restored.

In addition to the cemetery, you can find Jewish cemeteries on the islands of Terceira , and Faial .

Thanks to its geographic position and the presence of Brindisi, Otranto, Bari, Trani and Barletta ports, Apulia has been a transit point for many Jewish exiles -most heading to Israel. This crossing point therefore made of Puglia a privileged region for the Western Europe diaspora.

The first evocation of a Jewish presence in Puglia was written by Rabbi Akiva (17-137): en route from Jerusalem to Rome to plead the cause of the Jews of Jerusalem to the occupant, Akiva made a stop in Brindisi as mentioned in his diary.

Not all the Jews who settled in Apulia arrived directly from Palestine, as refugees from Jerusalem. Some arrived by sea from the Balkans, others from Spain and Portugal, or overland from France, Central Europe and other parts of Italy. In Apulia, they assimilated with existing groups, creating a Judaism with its own unique profile.

Jewish culture in Apulia, whose legacy is today primarily known in areas outside Italy’s peninsula, was highly esteemed in the Middle Ages. The twelfth-century French rabbi, Rabbenu Tam, compared Bari and Otranto to Jerusalem, paraphrasing Isaiah 2.3: “From Bari the Torah will come out and the word of God from Otranto.”

Traces of Jewish multiculturalism in Southern Italy are everywhere evident in the collection of annotations of the Pentateuch known as Sefer ha-Yashar (Book of the Righteous), that is believed to have been compiled in Naples in the late fifteenth century from pre-existing materials – the authors taking their cue from the narrative sections of Genesis and Exodus to tell parallel stories that occurred in other periods and areas. One of the central themes of this work is the migration of peoples. It explains, for example, that the population of Apulia and Italy all originate from biblical figures; and that Aeneas – the founder of Rome – was closely related to the patriarchs. Their tendency to draw parallels between different cultures shows that the Jews of Southern Italy were not closed to the traditions of other peoples, and that their ability to adapt was considerable.

An interesting illustration of the kind of multiculturalism that distinguished Medieval Apulia can be found in the decorative plan of the mosaic floor of Otranto Cathedral – the work of a twelfth-century Byzantine monk. The author fused elements drawn from the Bible and other Jewish narratives (similar to those that make up the Sefer ha-Yashar), elements that are rooted in a multi-ethnic culture, where Neo-platonic and Aristotelian traditions coexist with mythological material derived from Celtic folkloric literature. Realized during the Norman Era, this work is a tribute to the great Byzantine capacity for cultural synthesis that the new rulers sensibly adopted – doubtless to safeguard the diverse heritage of their newly conquered territories.

As time passed and dynasties succeeded one another, the centralization of culture in the capital led to a weakening of Jewish culture in the peripheral areas of the kingdom. This phenomenon may also be associated with instability due to socio-political feuds. The social composition of the community continued to change. At the time of the transition of power from the Byzantines to the Normans, many Jews migrated to northern Italy and from there to the Rhineland, where they contributed to the formation and enrichment of Ashkenazi liturgical and philosophical traditions.

After World War II, Apulian Judaism got a new lease of life for a few years between the end of the conflict and the establishment of the State of Israel, when thousands of Jewish refugees from central and Eastern Europe and the Balkans, mainly survivors of Nazi concentration camps, stayed in the transit camps managed by the United Nations. To prevent them from reaching Palestine, the Allied Forces temporarily relocated them to Santa Maria al Bagno, Santa Maria di Leuca, Santa Cesarea, Tricase, Bari, and Barletta where they immediately recharged community organizations, religious schools and political institutions. Source : Fabrizio Lelli, « Judaism in Puglia as a Metaphor for Mediterranean Judaism ».

In this region of Ukraine, the happy and unhappy history of Ukrainian Jews can be seen in these different towns. When you greet the violinists on the rooftops of Lvov, you will think of Scholem Aleikhem. Czernowitz, meanwhile, was home to many synagogues and was also the birthplace of Paul Celan. Synagogues are often reduced to walls or commemorative plaques. Like the remains of the sublime synagogues in Brody and Zolkiew. Memories, vestiges of memory, are also happy when thinking of Medzhibozh, the town of the Baal Shem Tov, and unhappy when meditating in front of the Memorial to the Victims of the Rovno Massacre.